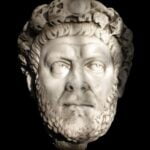

Constantine I the Great (Gaius Flavius Valerius Constantinus) stopped persecuting Christians and was baptized before his death, becoming the first Christian ruler. He was recognized as a saint in the Orthodox Church. But was he really so holy? When we delve into his biography, we come to the conclusion that he did not differ much from the power-hungry “wicked emperors” who condemned people to death without blinking an eye. Christian virtues were alien to him, especially love for his neighbour and forgiveness.

Constantine was born on February 27, around 280 CE. in Nis (now Serbia). His father was Constantius Chlorus, and his mother was Helena (later recognized as a saint). In 293, under the tetrarchy (rule of four; two Augustus and two Caesars) introduced by Diocletian (Roman Emperor 284-305), the father was given the title of Caesar of the West and ruled over Gaul and Britain.

Tetrarchy did not specify, in the event of the death of any of the rulers, who will take over. When Constantius Chlorus died in Britain in 306 CE, the legions hailed his son as the new emperor. In a letter he sent to his co-rulers, Constantine excused himself from the situation, suggesting that it was the legionaries who actually forced him to take over the title of his father. How much truth is there; is not known. In Roman history, we know a few examples when the emperor was chosen by force by the army. The co-rulers finally recognized his power, which, as it turned out, was the beginning of their end.

One of the first rulers who lost his title and lost his life was Maximian (born 250, died 310). His daughter, Fausta, married Constantine in 307, and the purpose of the union was to cement the alliance with her brother – Maxentius, who ruled in Italy. Ultimately, however, Maksymian organized a plot against his son-in-law, also trying to involve his daughter in his plans. Unfortunately for her, she told her husband about everything. The conspiracy eventually failed. All the torturers were exterminated, and Constantine spread a rumour that his father-in-law had allegedly committed suicide himself.

The aforementioned Maxentius, Brother Fausty, did not rule for long. In 311 he lost Spain to Constantine, and on October 27, 312, both rulers fought a battle at the Mulvian Bridge. The much larger army of Maxentius was pushed to the bank of the Tiber, and Maxentius himself was killed while trying to cross the river. The victorious Constantine thus became the independent ruler of the empire in the west. The next day, he triumphantly entered Rome. The emperor allegedly had the body of his brother-in-law found, cut off his head and flaunted in triumph in the streets of Rome.

The last tetrarch, Licinius, stood in the way of Constantine’s full power. Initially, they were allies and, inter alia, together they signed the Edict of Milan in CE 312 which allowed Christians to profess their religion. Moreover, in the same year, Licinius married Constantine’s sister – Constantia. There were two rulers in the Empire at the time: Licinius ruled all over the East; in the west, Constantine.

Relative understanding and harmony were only a blur. In fact, they were both getting ready to fight. In about 314 there was a clash at Cibalae, which ended in the defeat of Licinius. Another major battle took place in 324, which also ended in a victory for Constantine. The defeated Licinius initially kept his life, but in 325 the emperor (based on information about the planned plot) ordered the murder of Licinius and his son.

From then on, Constantine ruled alone. That same year, he decided to move his capital to Byzantium, a city that was renamed Constantinople.

In 325 CE unexpectedly, the emperor sentenced his son from an informal relationship with Minerwina – Crispus – to death. Historians are wondering what was the reason for this decision. Zosimos (a Roman historian from the 5th century CE) claims that the person responsible for this decision was Faust, who wanted to get rid of her stepson and ensure the succession to the throne for her children. The empress was to convince her husband that her stepson had allegedly wanted to seduce and rape her. This is very similar to the story of Joseph and Putyfar’s wife; in this story, the woman also wanted to seduce the young man, who, however, rejected her advances. Constantine, known for his impetuous character, could therefore believe his wife and condemn his son to death.

Faust, however, must have had something on her conscience. Soon she shared the fate of her stepson and lost her life in a peculiar way – she was “cooked” in a bathhouse. When Faustus, unsuspecting of anything, was taking a bath, the door was bolted and the water heated to such a high temperature that she finally gave up her ghost.

There is probably no doubt that the deaths of Crispus and Fausta were related. Some historians say they actually had an affair. Others believe that the emperor learned after the execution that Fausta was lying and condemned his son to death without justification. Independently, Konstantyn condemned Faust to damnatio memoriae; her name could not be mentioned anywhere and was to be removed from official documents and inscriptions on monuments forever.

Was Constantine I rightly included among the saints? One may have ambivalent feelings about this. Although he endured the persecution of Christians, he also had a lot of blood on his hands, including his own family. Constantine supported the new religion and was even baptized, but was a “heathen” almost to the end of his life. Before his death, he signed a decree under which he exempted priests who dealt with the cult of the ruling family from paying taxes and other benefits. He was still a god for the Gentiles, and a new apostle for Christians. Interestingly, after his death, he was buried in the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople. Finally, his will was fulfilled, and 12 other empty sarcophagi were placed around his coffin. This was to symbolize the 12 apostles, where he himself was to be considered the thirteenth apostle, the most important.