Chapters

Hannibal was born as Hannibal Barcas (also referred to as Barca) in 247 BCE. He was one of the greatest opponents of Rome and one of the greatest generals in history.

Origin and youth

Hannibal was the son of Hamilcar Barcas, commander of the army of Carthage. He had several sisters and two brothers: Hasdrubal and Mago. Apparently, as a child, Hannibal was almost sacrificed.

After the defeat of Carthage in the First Punic War, Hamilcar Barcas decided to improve his family status and Carthage’s income. To this end, he decided to conquer the tribes inhabiting the Iberian Peninsula. At that time, the Carthaginian army was so devastated that Hamilkar could not use the fleet and had to march with it to the Pillars of Heracles, from where they were to be transported to Iberia. According to Polybius, Hannibal was begging his father to agree to take him with him. Hamilcar agreed, however, on condition that the son swears his hostility to Rome until his death.

During the war in Spain, Hannibal’s father drowned. His place was taken by Hannibal’s brother-in-law – Hasdrubal the Elder – with whom Hannibal became an officer. Hasdrubal made an agreement with the Romans that designated the Ebro River in Spain as the natural border of Carthage and Rome. In addition, numerous alliances with local Spanish tribes were established.

Second Punic War

In 221 BCE Hasdrubal was murdered as a result of an assassination attempt, and Hannibal took command. During his two years in office, Hannibal expanded Carthaginian estates in Spain. Rome, fearing Hannibal’s growing position and strength, allied with the city of Sagunto, which was a short distance from the Ebro River. The Romans proclaimed Saguntum their protectorate, which Hannibal considered a breach of the deal. However, this was not the main reason for the war. Hannibal had been planning an attack on Rome for a long time.

In 219 BCE Hannibal besieged Sagunto and conquered the city after eight months. The Romans demanded justice in Carthage and punish the Carthaginian leader. Hannibal, however, had strong support from the people who remembered the humiliating defeat of last war. At the end of the year, the government officially declared war on Rome. In this way, the Second Punic War began.

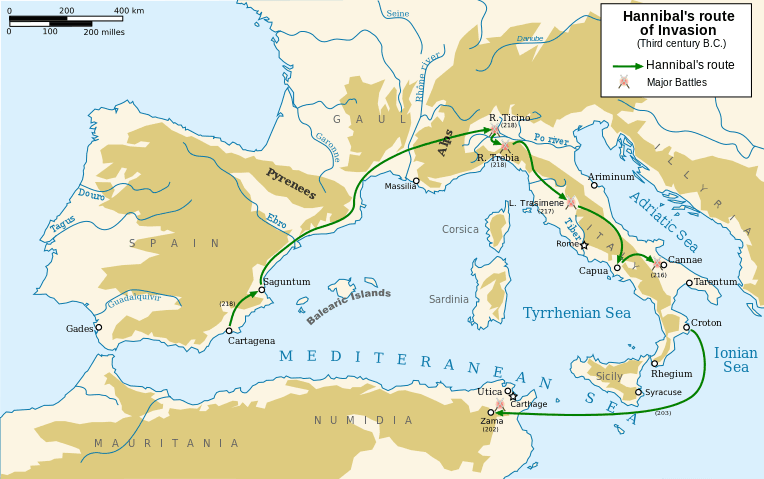

Hannibal set out from Spain with an army of 60,000 through the Pyrenees, southern Gaul, the Alps to Italy. After crossing the Alps, in November 218 BCE, he defeated in the battle of Ticinus Roman troops composed of velites and equites, commanded by Consul Cornelius Scipio, who in the fight suffered heavy injuries, and his son Publius saved him from death. Then Hannibal won the army of the second consul Sempronius on the Trebia River. The harsh winter in northern Italy caused the death of his elephants. However, he caused many defeats after the Roman army, including at Lake Trasimeno and near Cannae on August 2, 216 BCE After this last defeat, Roman troops did not take up already open battle.

No one can withhold admiration for Hannibal’s generalship, courage, and power in the field, who considers the length of this period, and carefully reflects on the major and minor battles, on the sieges he undertook, on his movements from city to city, on the difficulties that at times faced him, and in a word on the whole scope of his design and its execution, a design in the pursuit of which, having constantly fought the Romans for sixteen years, he never broke up his forces and dismissed them from the field, but holding them together under his personal command, like a good ship’s captain, kept such a large army free from sedition towards him or among themselves, and this although his regiments were not only of different nationalities but of different races. For he had with him Africans, Spaniards, Ligurians, Celts, Phoenicians, Italians, and Greeks, peoples who neither in their laws, customs, or language, nor in any other respect had anything naturally in common. But, nevertheless, the ability of their commander forced men so radically different to give ear to a single word of command and yield obedience to a single will. And this he did not under simple conditions but under very complicated ones, the gale of fortune blowing often strongly in their favour and at other times against them. Therefore we cannot but justly admire Hannibal in these respects and pronounce with confidence that had he begun with the other parts of the world and finished with the Romans none of his plans would have failed to succeed. But as it was, commencing with those whom he should have left to the last, his career began and finished in this field.

– Polybius, Histories XI.19

For the next 10 years, Hannibal fought in Italy. Due to the thinness of his strength, he did not take Rome. The purpose of his actions was to divert his allies from Rome. Ultimately, only a few cities in Italy, such as Kapua in Campania, decided to support the Carthaginian. In 204 BCE, the Scipio Africanus landed in Carthage, forcing Hannibal to withdraw from Italy and the battle of Zama in 202 BCE he defeated his army. Carthage lost all its possessions except Africa and had to pay a contribution and subordinate its foreign policy to Rome.

Hannibal after the war

Hannibal was over 40 right after the war ended. As it turned out, he could act not only as a soldier but also as a politician. After signing the humiliating peace as a result of which Carthage had to: (1) give up all possessions except North Africa; (2) pay huge war reparations of 10,000 talents; (3) reduce the fleet to just 10 units, Hannibal decided to focus on politics. He was elected a ceiling, the highest government official, with strong executive power and considerable legislative and judicial powers. The position probably did not guarantee command over the army, but the office allowed him to rebuild his position.

Hannibal, however, had to deal with the constant attacks of the Carthaginian oligarchy on himself. Local families were jealous of Hannibal’s accomplishments and accused him of treason. For example, he was pointed out that he had not conquered Rome when he had the opportunity to do so after Cannae.

In the meantime, Scipio Africanus, when he was a member of the Roman commission regarding the settlement of the dispute between Carthage and Massynisa, reportedly met with Hannibal. Then the conversation took place:

Scipio asked Hannibal, “whom he thought the greatest captain?” and that he answered, “Alexander, king of Macedonia; because, with a small band, he defeated armies whose numbers were beyond reckoning; and because he had overrun the remotest regions, the merely visiting of which was a thing above human aspiration.” Scipio then asked, “to whom he gave the second place?” and he replied, “To Pyrrhus; for he first taught the method of encamping; and besides, no one ever showed more exquisite judgment, in choosing his ground, and disposing his posts; while he also possessed the art of conciliating mankind to himself to such a degree, that the nations of Italy wished him, though a foreign prince, to hold the sovereignty among them, rather than the Roman people, who had so long possessed the dominion of that part of the world.” On his proceeding to ask, “whom he esteemed the third?” Hannibal replied, “Myself, beyond doubt.” On this Scipio laughed, and added, “What would you have said if you had conquered me?” “Then,” replied the other, “I would have placed Hannibal, not only before Alexander and Pyrrhus, but before all other commanders.”

– Titus Livy, Ab urbe condita, XXXV, 14

Hannibal in his office made many reforms. He contributed to the democratization of the regime; to this end, he reformed the ‘hundred and four’ court tribunal and introduced that members were elected at the people’s assembly; introduced the term of office of the office: two years (from life). In addition, his cost-effective policy allowed full repayment to Rome without imposing additional taxes. Seven years after the battle of Zama (202 BCE), Carthage “rose from its knees”.

This fact did not go unnoticed. Concerned Romans began to demand Hannibal’s resignation. Roman intrigues eventually forced Hannibal to go into exile on his own will. The Carthaginian leader first went to Tire – the original homeland of the Carthaginians, then to take refuge at the court of the Seluceus ruler Antiochus III the Great. The Syrian ruler was preparing for the war against Rome, and Hannibal offered him help and command of some of the troops. Among other things, he suggested an invasion of southern Italy. Ultimately, Antiochus III did not give Hannibal any significant office.

After Antioch’s defeat in the war with Rome in 189 BCE, he fled to Crete, and then went to Bithynia, ruled by king Prussia. He then fought with Rome’s ally – King of Pergamon Eumenes II. Hannibal offered his services in conflict. He led Prussian’s army to victories both on land and at sea. Over time, however, the Romans began to threaten Bithynia and ordered to capture Hannibal. Eventually, Prussia agreed to hand Hannibal to the Romans.

Death

When Hannibal learned that the king wanted to give him to Rome, he decided to commit suicide. In the city of Libyssa (present city of Gebze in Turkey), he drank the poison he had received from his father and always carried it in his ring so that he would not fall into the hands of the Romans and be put in a cage during a triumph. Before consuming the poison, he left a letter in which he wrote: “Let us free the Romans from their long anxiety since they claim that it is too long to wait for the death of an old man.”

The exact year of Hannibal’s death is uncertain. The Roman historian, Attic in the “Book of Annals” claims that he died in 183 BCE, as confirmed by Titus Livy. Polybius, who lived closer to Hannibal, gives 182 BCE. In turn, Sulpicius Blitho mentions 181 BCE.