Chapters

Even the greatest of strategy geniuses needs a handful of luck to win. Gaius Julius Caesar, who is still considered one of the greatest generals in history, was not invincible. At one point in the civil war against Pompey, Caesar was only saved from defeat by a miraculous coincidence. How is it possible that this “god of war” came within a hair’s breadth of tragedy? What decision saved him at the last minute?

Background

The war between the two most powerful personalities in Rome was inevitable. After its symbolic beginning in 49 BCE, which was Caesar’s crossing of the Rubicon River, the Caesarians pushed Pompey’s supporters out of Italy and Spain. So Pompey began to gather his forces in Greece. As Caesar notes in his work Civil War: “Pompey had a year to prepare his forces. […] He formed eight legions from Roman citizens”. These were significant forces that Caesar had to break at all costs to end the war. In January 48 BCE he crossed the Adriatic at the head of 15,000 soldiers, landing in Epirus. The second army that sailed from Italy was commanded by Mark Antony. Caesar captured several enemy strongholds and then marched towards Dyrrachium, where Pompey had fortified himself.

Armies

Caesar had 15,000 men under his command. Some of these troops were veterans of the Gallic wars, but their number was not that significant, as one of Pompey’s commanders, Titus Labienus, noticed before the battle. One of the legions under Caesar’s command was the Legio IX Hispana, today considered one of the oldest and most famous Roman legions, mainly due to the mysterious disappearance in British soil in 120 CE.

The help for Caesar in this campaign was to be Mark Antony, who commanded a force of about 20,000 soldiers.

Pompey gathered much larger forces in the vicinity of Dyrrachium, numbering as many as 45,000 people. Some of his officers were Caesar’s former subordinates, such as the aforementioned Labienus. Despite such a great advantage, Pompey felt no need to give Caesar a battle. He hastened to Dyrrachium before Caesar, and he did not want to lose the city because of the great number of armaments there, so he fortified himself in its vicinity. Gnaeus Pompey’s army had the sea behind them and Caesar’s army approaching in front of them.

Before the battle

Julius Caesar also had no intention of starting a battle with Pompey’s much stronger forces. Instead, he also ordered the construction of fortifications so as to cut off Pompey from food and water supplies. During the construction of the fortifications and after they were erected, there were constant clashes between the two armies. However, the commanders avoided fighting a major battle. Supply was a problem for both armies. Pompey’s cavalry was threatened by the lack of fodder for horses, and Caesar’s army by starvation. The tense situation and constant skirmishes between the parties inevitably led to open fighting.

Battle

At dawn on July 10, Pompey’s units attacked two cohorts of the 9th legion, which was working on the still unfinished fortifications to the south [see: Battle Plan]. This was a weak point in Caesar’s defenses. The defenders suffered heavy losses and there was a great risk that the Pompeians would break the siege. However, the difficult situation was noticed in time by Mark Antony, who arrived with reinforcements and only thanks to his help it was possible to maintain the position. Pompey’s soldiers, however, captured the well-fortified Caesarian camp.

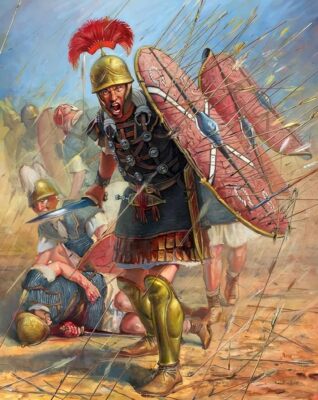

Caesar could not allow such a situation. It was necessary to recapture the camp and drive Pompey’s cohorts back. So he personally led out 33 of his cohorts, including the decimated 9th Legion, and quickly attacked Pompey’s legion in the camp he had occupied. The surprise was complete. Gnaeus Pompey did not manage to send support to the defending legion. The Caesarians began to break through the ramparts and reclaim the fortifications lost in the morning. And then something happened that turned the tide of this battle to Caesar’s disadvantage.

Well, the Caesarian cohorts attacking the fort on the right flank at some point lost their orientation in the area and went far towards the river and the sea. Seeing this, Pompey quickly moved some of his troops to this place and caused panic in Caesar’s army. The legionnaires and the cavalry began to flee. Many people have been trampled. The left-wing, seeing the panic on the right flank, also began a dramatic retreat. The soldiers rushed jumping over the embankments, ignoring their wounded comrades. Caesar tried to control his panic. He arrived at the place of fighting and tried to turn the soldiers back personally, “but still some, having lowered their banners, ran on the same road, others abandoned them out of fear, and no one stopped at all”. The attack thus Caesarian ended in panic and a dramatic retreat which Julius Caesar was unable to stop. His troops on the left wing began to withdraw, leaving the unfinished fortifications in the south to the enemy. Everything pointed to the inevitable defeat of Caesar. It was enough for Pompey to attack with all his strength now. Yet something happened that saved Gaius Julius Caesar from disaster.

Well, as Caesar himself writes about it, Pompey suddenly stopped the attack and ordered the soldiers to return to their positions, because he was afraid of a trap. First, he couldn’t understand why the initially victorious attack suddenly stopped and the enemy soldiers began to flee. Secondly, he knew Caesar very well and knew that he was a clever and cunning leader. So he concluded that it was probably a trick. He didn’t want to risk big losses. Caesar’s men, fleeing in panic, were not pursued and were not killed. Pompey was sure he had avoided the trap. Caesar certainly did not fully understand what had happened himself. He lost the battle but came out unscathed.

After

Caesar’s losses in the battle are, according to himself, 990 men plus 32 centurions and several more notable men. Most of them, however, did not die in combat, but were trampled while fleeing. Perhaps Caesar’s losses were greater, but it is difficult to determine. Pompey lost over 2,000 men.

On the night of July 10-11, when Pompey was rejoicing in his victory and the lifting of the siege, Caesar withdrew, leaving two legions in order to confuse the enemy. The next day, Pompey realized his position. He was left alone on the battlefield while Caesar managed to leave with his army to safety. He quickly sent the cavalry in pursuit, but they had no effect.

Pompey, confident after winning the battle, followed Caesar towards Thessaly. There, in 48 BCE, the decisive battle of the entire civil war took place. Caesar routed Pompey’s army at Pharsalus on August 9. This victory turned out to be complete and final.

The Battle of Dyrrachium shows that there are situations in war when even the most brilliant commander cannot prevent a catastrophe. However, it turns out that very often a significant role is also played by lucky twists of fate.