Chapters

Battle of Thermopylae (191 BCE) was the victory of the Romans over the army of the Selucid king Antioch III. The clash took place in the legendary Thermopylae Gorge, where the Spartans defended themselves three centuries earlier.

Historical background

Among the many countries that emerged from the ruins of the Alexander the Great, the largest area was occupied by the power ruled by the descendants of Seleukos. The flourish during the reign of Antiochus III called the Great, at the turn of the third and second century BCE This ruler was able to strengthen the state by defeating the claimants to the throne and organizing the famous Eastern expedition. Encouraged by these successes, he reached for the Greek cities on the coast of Asia Minor and sent his army to Europe. These actions, however, were unacceptable to the Romans, increasingly interfering in the affairs of the conflicted Hellas. The result of bilateral disputes was a conflict called the Syrian war, the culmination of which was the struggle in the Thermopylae Gorge, known for the heroic Spartan battle led by Leonidas.

The conflict between Rome and the Seleucid monarchy is a sensation in the history of the Republic’s relations with the Hellenistic countries. As noted by the outstanding Polish historian Tadeusz Wałek-Czernecki, it was at that time that there was no significant potential difference between the warring parties, which gave the chance to stop the march of the Republic from above the Tiber towards the position of world power. It is not without reason that the Austrian historian Heftner called the Syrian war an armed clash of ancient superpowers.

The beginning of mutual disagreements is related to the actions of Antiochus III, who concluded a secret pact with the king of Macedonia Philip V, sanctioning the partition of the Ptolemy kingdom. According to its provisions, Antioch was to receive lands belonging to the Egyptian monarchy: Syria, Phenicia and Palestine. This increase in the importance of the Seleukid state must have caused anxiety among members of the Senate, closely watching the events in the Eastern Mediterranean. After absorbing the Greek poleis on the coast of Asia Minor, Antiochos transferred the army to proper Greece and captured the Thracian Chersonesus.

Meanwhile, after defeating Hannibal in a heavy battle and defeating Philip V at Kynoskefalai, she felt more confident about her recent allies. Former Allies of the Republic in Greece, the Ethols felt betrayed and deceived by the Romans. In exchange for help in defeating Macedonia, they did not receive the consent of the Senate to build their power in Hellada. The Romans did not liquidate the Philip’s state as expected by the Ethols, they did not give them all of Thessalia, granting only minor territorial acquisitions. The highlanders from Etholia watched the possessiveness of the Republic with growing irritation. So they were looking for an opportunity to find an excuse for revenge on the Romans. It was the Ethols who strongly encouraged Seleukida to intervene in Greece, urging him to free the people of Hellas from Roman oppression. Antioch himself was furious at the Romans because they demanded that he withdraw from Greece and Greek cities on the coast of Asia Minor. When the Ethols took over the important fortress of Demetrias on Pasagaj Bay, the ruler realized that it was too late to avoid war.

Forces of both sides

In the fall of 192 BCE Antiocho landed in Greece with an army of only 18,000 warriors. The ruler was counting on the general anti-Roman uprising of Greeks and the help of King Philip V, who was recently humiliated by the Republic in the Second Macedonian War. However, the people of poleis were not interested in fighting the Romans, and Philip could not forgive Antioch for his support of another claimant to the throne of Macedonia. Antygonida no longer had the strength to fight the Republic and became a faithful executor of her will. Importantly, Antioch did not know who he would face. While Hellenistic diplomacy was marked by a kind of pacifism, the Romans understood war as a life-and-death struggle. For them, the armed conflict ended when the enemy was made unable to resist or annex its territory. The status of the defeated party had to be reflected in peace treaties, imposing drastic reinforcements on the defeated. The Roman way of waging war was completely alien to Antioch and other Hellenistic rulers, for whom the peace treaty was to satisfy both sides and reflect in their records their relative strength. Such a policy also assumed the possibility of mediation on the part of a third country interested in peace in the region.

In fact, there was only one option before Antioch – complete destruction of the Republic over the Tiber, which was impossible due to the poor recruitment resources of the Seleucids. Upon hearing of Antioch’s landing in Greece, the senate began preparations for a war against him. The Roman patres were well aware of the difficult task ahead of them. Antioch was, after all, radiant with the fame of an energetic ruler who successfully won great spoils in his expedition to the East. The alliance of Seleucids with other countries defeated by the Republic, such as Carthage and Macedonia, was also feared over Tiber.

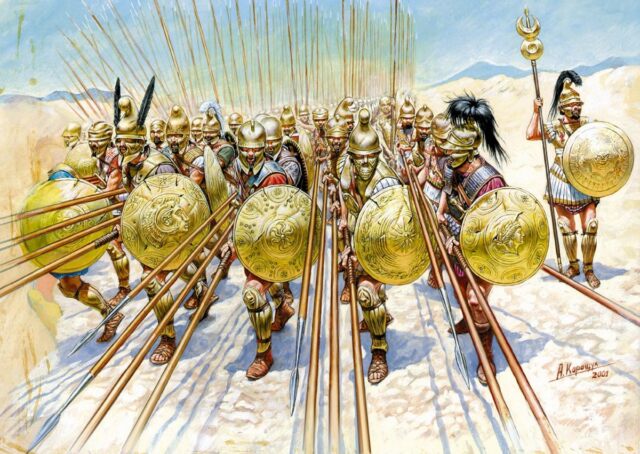

So troops were sent to Taranto to observe the sea shores and a fleet to patrol the sea. An army of 20,000 legionaries and 40,000 allies was formed against Antioch’s army. Meanwhile, the king reached his former battlefield at Kynoscephalae, where he buried the remains of fallen Macedonians to kidnap the people of Macedonia. This reckless act only caused hatred of Antigonid, who now strongly supported the Romans in this conflict. Antioch made another mistake – he neglected to train his army, which spent the next winter inactivity and entertainment. Antioch’s weakness made itself felt in spring, during the royal army’s operation in Akarnania. Meanwhile, the Roman army, consisting of 2,000 cavalry and 20,000 infantry, 15 elephants and several Ilirów light troops, entered Thessaly. These forces were strengthened by the army of Consul Bebiusz, who had been successfully conducting military operations against Seleucid. In total, Roman forces numbered 30-40,000 soldiers. Frightened by the enemy’s progress, Antiochos regrouped and took up position on the famous pass in Thermopylae, where he planned to wait for reinforcements from Asia. He now had 10,000 infantry, 500 horsemen, 6 elephants supported by a troop of 4,000 Ethols.

Battle of Thermopylae 191 BCE

The Thermopylae Pass is a long and narrow passage, surrounded on one side by a sea without ports, on the other by inaccessible swamps and mountainsides. Above the pass are two mountain peaks – Kalidromon and Tychiunt. Here there are sources of warm waters, hence the name Thermopylae (Greek “warm gates”). In the ravine, Antiochus had to dig across the ditch and build two embankments one after the other, with the front embankment lower. To the right, the fortifications bordered the sea, to the left the embankment passed into a stone wall stretching less than 2 km to the south. It was on the wall that Seleukida set up war machines and several hundred archers, javelins and slingers. Lightly armed and pellets took the position before the embankment, while the phalanx stood in the center at the lower ramparts across the pass. This position gave the phalanxes an advantage over the enemy who had to attack in a narrow column. Finally, on the right flank touching the bay stood the king with 500 horsemen and 6 elephants. The positions of Antioch’s troops from the sea were secured by his fleet near Konaion and garrisons in Demetrias and Chalkis.

Seleukida planned that the fight against the ramparts would be started by light armed men, supported by shooters located on the wall and war machines. The impending column of legionaries attacked from the side with a hail of missiles, torn from the front by light-armed skirmishers, was to be forced to retreat. Antiochus’ riding and elephant attack was to pogrom retreating Roman infantrymen. However, if the light-armed men succumbed to a strong legionary infantry, then a trench and phalanxes on the embankment awaited them. There was still security left behind the army. After all, the king must have known the stories of the Persians who found the way to the rear of the Spartans. To protect himself from an attack from behind, the king ordered the Etols to occupy the mountain peaks to control the passages towering over the pass. The Ethol warriors occupied three strategic peaks – Kalidromon, Tychiunt and Roduntia, building temporary fortifications on them. The Roman commander, Manius Acilius Glabrion, seeing the prepared opponent, decided to attack the pass frontally the next day at dawn. Some legionaries reviewed their shells and armaments before rest, and troops commanded by Mark Porcius Cato and Lucius Waleriusz Flaccus set off at night along mountain paths to circumvent Antioch’s position from behind. The task of this “night expedition” was to displace the Ethols from their vertices and attack the enemy’s position in Thermopylae.

Flaccus’s legionaries did not succeed in the attack on Tychynth and Roduntia. The Catoa group, after entering the famous “Efialtes’ path”, broke through the mountain trails among the moonless night, steep rocks and dangerous chasms. After boring adventures with guides and difficulties in finding the right path, the stubborn tribune identified Kalidromon below his position, where the Etol fortifications were located. From the confession of prisoners he learned that the summit was defended by only 600 people. With more than three times the advantage, Cato picked up his unit and headed for them from above. The Ethols finally succumbed to legionaries after a fierce battle. Meanwhile, there was a fierce battle on the pass. The light-armed Antiochus at first tugged at the Romans from many sides, on which from the side a hail of arrows and projectiles were falling. However, when they regrouped and pushed the opponent towards the ditch and embankment, the phalanxes parted, allowing exhausted light fighting to cool down behind them. The Romans, after breaking through the ditch, had to face terrible rows of saris from above.

The situation of the legionaries, bombarded with bullets from the side and from the higher shaft on the pass, was unenviable. It seemed that nothing would take away the glory of winning Seleucid. Suddenly a great scream was heard at the rear of the royal army. Seleucid soldiers standing on the ramparts noticed the ethol soldiers running from the hills towards them. It seemed that the Ethols, after defeating the Romans, were running to their aid. What was their surprise when they realized that their allies were fleeing the pursuit of Cato’s legionaries. The Roman commander cautiously led his subordinates not to the enemy troops standing on the upper rampart at the pass, but to Antioch’s camp. Seeing this, the Seleucid soldiers immediately left the secure positions on the ramparts and went to save their wealth accumulated behind the fortifications of the camp. The whole intricately prepared defense of the pass has now broken. Glabrion’s legionaries crossed the ditch and embankments without obstacles, flooding the pass, where they slaughtered Antioch’s soldiers. Interestingly, at the same time some of the Ethol troops took over the Roman camp, defeating its crew! However, seeing this, the legionaries on the pass did not abandon their tasks until they crushed Seleucid’s army. It was only when the enemy was completely beaten that they started to recapture their camp from the hands of the Etols. Roman cavalry chased the escaping royal soldiers all the way to Skarphei on the Malian Gulf.

A king rescued from the pogrom, who led 500 riders to Elatea, from where he gathered the survivors to gallop to Chalkis. His army’s losses were severe. According to Appian and Livius, 10,000 Antioch soldiers were killed or captured. Although these figures may have been overstated by these historians, one can be certain that few Seleucid walkers survived. The losses of Glabrion’s army were small and numbered 200 legionaries who died in battle and pursuit.

The meaning of the battle and summary

The Battle of Thermopylae marks a turning point in the history of the Seleucid state. From then on, their power was inexorably falling. Other territories slowly lost up to the first century BCE, when Pompey deprived the last king, Antiochus XIII of Asian power. The battle on the pass in 191 could have taken a completely different turn. Antioch III perfectly planned the fight, but his army’s weak discipline compared to the Romans failed. Her soldiers could win the battle by attacking Cato’s soldiers encircling them from behind. However, their poor morale, caused by the misuse of the winter before the battle, ruined this opportunity.

Unlike disciplined legionaries, Antioch warriors preferred to save their wealth in the camp than to turn against Cato’s legionaries. This error proved decisive for the outcome of the battle. The Romans won it thanks to the stubbornness and determination of their troops sent to the rear of the enemy, numerical superiority, perseverance of the army frontally attacking the pass and mere luck. These qualities have made them the undisputed rulers of the entire Mediterranean basin.