Chapters

Livia Drusilla, was the third and last wife of Octavian, reigning from 27 BCE to 14 CE as Emperor Augustus. She was born on January 30, 58 BCE as the daughter of Livius Drusus, née Claudius, who died after the battle of Philippi. He was a supporter of Cassius and Brutus. She married Tiberius Claudius Nero in 43 BCE, who was her father’s nephew, and after divorcing him, she married Octavian on January 17, 38 BCE. In 14 CE, under the will of the late Augustus, she was adopted into his line as Julia Augusta. She died in CE 29 at the age of 86. Thanks to Claudius, she was deified in CE 42 as Diva Augusta. She had two sons from her first marriage: Tiberius and Drusus.

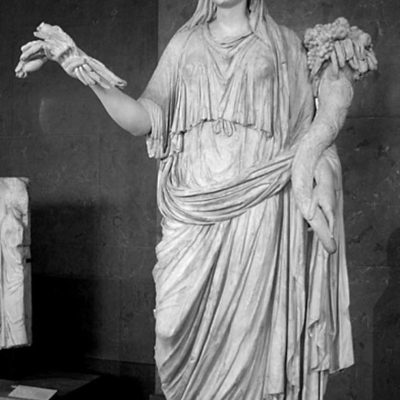

Portrait

Velleius Paterculus characterizes Livia as follows:

She, the daughter of the brave and noble Drusus Claudianus, most eminent of Roman women in birth, in sincerity, and in beauty.

– Velleius Paterculus, Historiae Romanae, II.75

From his statements, we learn about her impeccable beauty and noble origin. Besides, only such a Roman woman could become Caesar’s wife. Other sources do not comment on Livia’s beauty, only on her character and manner. However, we have iconographic sources, coins on which the empress was depicted with her husband, and later her son. Livia on the coins has classic facial features, considered beautiful and dignified at the time. She is often compared with Athena, hence on one of the coins next to Livia’s head there is a bust of Athena. It also has coins with only its own character, the reverse is decorated with an inscription, for example: “IVSTITIA/– C: IM T CAES DIVI VESPA AVG REST”. It is also often compared with Pietas, eg Livia with a diadem, a symbol of power, and the inscription: “PIETAS AVGVSTA”. Or in the veil itself with the inscription: “PIETAS/SC”, on the reverse: “DRVSSVS CAESAR TI AVGVSTI F TR POT ITER”. The image of Livia also appears with Julia’s face and with Augustus, and Gaius and Lucius on the reverse. An important coin is also a coin with the bust of Livia and Tiberius, and on the reverse she, not the son, appears on the throne. In addition to coins, there are also sculptures, where you can see her hairstyle, clothes and figure. We also have a sardonyx depicting Livia as a ruler sitting on a throne and at the same time the goddess of Augustus, with a diadem on her head, reminiscent of the Great Mother.

Silhouette in the eyes of historians

Velleius Paterculus writes about her devotion to her children, when she fled from Octavian “hugging his future son in her arms”, she crossed to Sicily with her husband Nero. The same Octavian in 38 BCE married Livia with the consent of her first husband and adopted her sons. Paterkulus shows Livia as an exemplary wife and mother who is completely devoted to her family, obedient and quiet, and worthy of imitation.

In Lives of the Caesars, Suetonius describes her escape from the city of Lacedaemon with her husband, when they nearly paid their lives when a forest fire scorched part of Livia’s robe and hair, and she was protecting little Tiberius from the flames. A good Roman woman, as Paterculus calls her, had to be faithful and devoted to the husband who ruled over her. Suetonius further describes her as a woman who believed in divination, when before conceiving a son she tried to find out who she would be, she warmed the hen’s egg until a chicken with an exceptionally beautiful comb appeared, thus prophesying a great future and even a royal crown for Tiberius. Belief in omens was common in Rome. Even Augustus, who visited the astrologers after Caesar’s death, wore a sealskin as protection against thunder, consulted the soothsayers, and feared misfortune when he inadvertently put his right foot in his left shoe in the morning. After her marriage to Augustus, Livia is said to have dropped a hen with a branch of laurel in its beak, dropped by an eagle. It was believed that from this twig in Livia’s villa grew a mighty tree, from whose branches future emperors wove a victory wreath.

Note how Tacitus describes her:

In the purity of her home life she was of the ancient type, but was more gracious than was thought fitting in ladies of former days. An imperious mother and an amiable wife, she was a match for the diplomacy of her husband and the dissimulation of her son.

– Tacitus, Annals, V.1

Earlier, Tacitus in his “Annals” writes about her firmness towards her sons, and fidelity to her husband, which in the end do not conflict with a good upbringing and love for her son and husband. However, many inconsistencies can be found in Tacitus. The previously mentioned passage from Tacitus is at odds with his vision of Livia as a woman who, “with a lust for power inherent in women”, tries to rule through first her husband and then her son. In the end, the historian again returns to the statement that only her person prevented Tiberius from the cruelty with which he later became famous.

No source describes her as a dissolute and uncultured woman. Historians consider her a faithful wife and caring mother. Nor was she greedy or jealous of the favours of others, like her son Tiberius. Caligula often referred to her maliciously as “Odysseus in a skirt”.

She was the first lady of the imperial court and took her duties towards this house and state seriously. It can be said that along with the strengthening of her external position, honours and distinctions that were not undeserved, also her self-confidence and, as some say, lust for power grew, hence she is often perceived from the outside as cold and politically calculating. Of course, she cannot be reproached too much for this, for she has never used her position to the detriment of the Empire. One would like to say that she obeyed Rome. Anyway, Cassius Dio also writes about this obedience, presenting her as always willing to help Augustus, advising him on various problems. She was also helpful to the senators. Neither Suetonius nor such a defender of the senatorial state as Tacitus writes about it. Cassius Dio writes about her: “Livia saved many senators, brought up children of many of them and helped many times to collect their daughter’s dowry. That’s why some called her Mother of the Fatherland“. what this historian draws attention to is her impeccable manners, which other historians have also written about.

…however, I can advise you if you will take my advice and don’t scold me because, although I am a woman, I dare to offer you something that no one else, not even among your closest ones, will accept friends would never dare advise you, not because they are ignorant of the matter, but because they dare not open their mouths.

At the end of the Republic, and especially during Augustus’ principate, there were many educated women, so Livia was not unique. If writers mention educated women, they do not treat this fact as an exceptional phenomenon.

Marriage

Livia’s first husband was Tiberius Nero. He had a completely different view on political matters than August, which made him his staunch opponent. And yet, an agreement was finally reached, thanks to which Livia met Augustus. As Gaius Suetonius writes, he married Livia when she was pregnant and “he loved her until the end”. Interestingly, August had many mistresses. Suetonius mentions that Mark Antony accuses Augustus, in addition to his hasty marriage with Livia, and that he led his ex-wife to the bedroom in front of the consul. As Suetonius describes: “Even his friends do not deny that he committed adultery, but they excuse him by saying that it was not passion that motivated him, but a reason of state: so that he could more easily trace the intentions of his adversaries through their wives.” According to our morality, this contradicts our love for Livia. In ancient Rome, however, it was different. We know that the Romans valued marriage very much. Especially Augustus paid special attention to the institution of marriage, believing that marriage should be guided by dynastic considerations. He did not tolerate the debauchery and betrayal of others unless it was a slave. For this reason, he exiled Julia, his daughter, as Suetonius informs us.

Marriage, of course, was about having children to pass on your life’s work. Unfortunately, Livia had no children with Augustus. Besides, from the point of view of the law, nothing compelled a husband to be faithful in marriage. The basic rule that was followed was the prohibition of having relationships with free-born Roman women. No one was scandalized when slaves or dancers were involved.

As for Livia, she was a faithful wife. Even if she is accused of divorcing her first husband. It was a completely legal divorce, with the permission of Tiberius Nero, and he even played the role of the bride’s dead father. It should be noted here that absolute fidelity and obedience were required of the wife. Livia was a faithful wife. She never betrayed August. Welleius Paterculus writes about it, but neither Suetonius nor Tacitus deny it.

Let’s go back to August’s love for a moment. Tacitus does not deny it. Augustus repeatedly succumbed to Livia, and he was often accused of it. Suetonius even suggests that it was Livia who suggested mistresses to her husband. However, this can probably be considered a slight exaggeration, bearing in mind that this historian does not verify facts with rumours. The same source points out that Augustus died in Livia’s arms, addressing his last words to her. The malicious would say that it may have been her propaganda that she invented it herself, as well as the fact that she did not immediately announce the death of her husband. She procrastinated. Another plot of hers. As Tacitus writes, she cordoned off the house and streets and spread good news from time to time. Here one could pay attention to Livia’s answer to the question of how she bound her husband to her. Cassius Dio writes about this and, as he claims, replied: “she obtained it thanks to the fact that she herself paid attention to morally impeccable manners, willingly fulfilled all his wishes, did not interfere in his affairs and, above all, gave the impression as if she did not notice and nothing heard of his affairs. In fact, it must be remembered that adultery was severely punished, and such a law was introduced by Augustus himself. On the other hand, it is worth paying attention to the words of Tacitus: “To seduce and be seduced is in fashion with us”. Which is confirmed by Cassius Dio. One cannot disagree with this. We know this from many sources. The marriage of Livia and Augustus is therefore no different from other Roman marriages. It is only necessary to pay attention to Livia’s attitude towards this marriage. She was, after all, an exemplary wife, loving her husband, and certainly faithful, which, moreover, was consistent with her impeccable upbringing. After all, she was the first, if not the only, Roman empress in the full sense of the word. It also brought Augustus to such a state that before talking to her, as suggested by Suetonius, he took notes: “he prepared himself in writing for more important conversations with particular people, even with his wife Livia, and during the conversation, he looked at these notes for fear that while speaking unprepared not to say too much or too little”.

Tacitus does not spare statements that Augustus succumbed to Livia, and to a great extent. “For she so possessed old Augustus that she banished her only grandson, Agrippa Postumus, to the island of Planasia”. As Tacitus explains, Postumus was innocent.

According to Suetonius, Livia was at the death of Augustus, who addressed his last words to her: “Livia, remember about our relationship, live and be healthy!”.

Death and testament of August

The death of Augustus and his testament are particularly controversial facts here. Suetonius describes the death of Augustus by marking the last conversation with Tiberius, which he mentions twice. The first time in the life of Augustus, the second time in Tiberius. Whereas, first, he suggests that some thought that Augustus had once said of Tiberius: “Wretched is the Roman people to fall into jaws so slowly crushing.” He further claims that he only adopted him because of Livia’s constant pleas. He refers here to many writers who see it this way and suggest, as he writes, “so that by giving such a successor one day I will cause all the more regret for myself.” Suetonius does not believe that such a wise ruler, as he says about him, chose as his successor someone who is not at all suitable for this. He cites a letter from Augustus to Tiberius, in which he praises him for his great commanding skills and the poem: “One man saved our state with his vigilance”. This view is completely different from Tacitus, who is more credible for us, as mentioned earlier: “Even Tiberius was not appointed by attachment or concern for the state as his successor, but having seen his arrogance and cruelty, he sought his own in the worst contrast to himself fame”. However, we must agree with those writers, such as Tacitus, who emphasized the cruel character of Tiberius. Also, Suetonius is not relatively consistent in this, as he discusses the faults of Tiberius. The reason for such disagreement may be a change in Augustus’ views. It is possible that Augustus when he got to know the character of Tiberius better, perhaps also wanting to avoid disputes with Livia, decided to change his earlier decision. Besides, it should be remembered that Augustus had no children to whom he could pass power. The special situation that developed at the imperial court could have caused Augustus to change his mind.

Another thing is the last words of Augustus to Livia. Tacitus says nothing about his conversation with Livia. On the other hand, Suetonius quotes the words of Augustus to Livia at the moment of her agony: “Livia, remember our relationship, live and be well!”. Earlier, he also tells his friends that if he played his role well in life, they would applaud him farewell, the same is suggested by Cassius Dio, quoting his last words: “I took over Rome as a brick city, and I leave you a marble city.” It is difficult to assess the consistency of this with how it really was. Tacitus merely suggests that some believed that Livia had caused her husband’s death.

Writing about Augustus’ will, Tacitus informs that it was delivered to the Senate by two Vestals, with whom usually important people kept their wills. Augustus listed the two main heirs of Tiberius and Livia. He took Livia into the family with the title of Augusta. Subsequent heirs are listed. Of course, Livia Augusta was from now on to be the priestess of the Augustan cult.

Suetonius is more specific here. He also writes about the Vestals who, together with their will, deposited three identically sealed scrolls in the Senate. There is an agreement between the two ancient historians as to the content of the testament. Moreover, Suetonius suggests that Augustus’ death was kept secret until the young Postumus Agrippa was killed. Suetonius doubts that Augustus demanded his death, rather he is inclined to blame it on Livia, who he suggests may have written the letter with or without Tiberius’ knowledge. Tacitus also believes that this sentence was not dictated by Augustus, but unlike Suetonius, he is more open and directly blames Livia and Tiberius, writing: “It is closer to the truth that Tiberius and Livia – he out of fear, she out of stepmother hatred – hastened the murder of a suspicious and self-loathing young man.”

Unfortunately, there is nothing about the will in Cassius Dio. However, in this case, it should be remembered that only small fragments of his work have survived.

Cult of Divine Augustus

Religion in the times of Livia and Augustus was combined with politics and official power. Two types of rites functioned in it: state and private worship. The cult was always guarded by priests (sacerdotes), elected and organized into colleges. Yet there was no religious centre to separate political life from religious life. Vestal women, priestesses of Vesta, played an important role in the religion in Livia’s time.

The cult of Divine Augustus is closely related to the person of Livia. As we already know in his will, Augustus adopted Livia to the Julian family and gave her the title of Augusta. In addition, “she also assumed the dignity of priestess of his cult as sacerdos divi Augusti”. It was, of course, an honourary title and did not concern the exercise of power. However, he was special because none of the women of the Julio-Claudian dynasty had the title of Augusta. The duties of the “sacerdos divi Augusti” included organizing ceremonies in honour of the deified Augustus and planning and funding his temples. And so Livia introduced after 15 CE in his honour “ludi Palatini”. They lasted from January 17 to 19, later extended to five days, and Caligula added three more days to them. January 17 was the anniversary of August’s wedding with Livia. Tacitus also mentions Livia consecrating a statue of the deified Augustus near the theatre of Marcellus in the year 22. According to the senate, Livia was to be entitled to a lictor, modelled on the Vestals. Tiberius, however, annulled this decision. We know that Tiberius was against the political activity of Livia, mainly those activities that could contribute to lowering his authority as a ruler.

All sources, including iconographic ones, often compare Livia with the Vestals. This is also the case with the dignity of Julia Augusta, who was probably associated with the goddess Vesta. The reason lies in her attachment to the Vestals. In 35 BCE Livia received personal immunity – sacrosanctitas.

She was the most dignified Roman matron, and matrons in ancient Rome had a similar status to vestals. Cassius Dio also suggests that Livia, during her illness in CE 22, was allowed to use the “carpentum”, a cult cart that was used to carry statues of the gods and priestesses of Vesta.

Tacitus in “Annals” writes that in 24 CE she also received the right to sit among the virgins of Vesta. Livia as “sacerdos divi Augusti” remained forever in a subservient role towards her divine husband and “father”, even after her own deification. In the times of Tiberius, Livia was depicted on coins as a seated priestess in a veil, with a patera and a sceptre. Such coins could be found in Carthage, Pestum, Lepcis Magna, Utica, Thapsus, Hippo, Diumia, Corinth, Knossos, Antioch of Pisidia, Cyprus and some Spanish cities. This is how Livia is also depicted on the engraved sardonyx: the enthroned Livia as a priestess of the deified Augustus, holding a bust of Augustus in her hand.

Today it is difficult to say whether immediately after Livia’s death anyone received the dignity of “sacerdos divi Augusti”. Certainly, this office was conferred on Antonia the Younger, but in the time of Caligula. Probably after 29 CE: Antonina the Younger, Agrippina the Elder and Julia Livilla were candidates for this title, because they were all widows at that time, which was an important element to obtain this office. Suetonius does not elaborate on the cult of the divine Augustus. He writes about the will, but his information is more geared towards finding the plots of Livia and Tiberius than the facts.

Death

Livia fell seriously ill in CE 29 and died shortly after at the age of 86. The consuls at that time were Rubelius and Fufius. She was one of the longest-lived empresses. Cassius Dio writes that Tiberius did not visit Livia during his illness. After his mother’s death, he showed no reverence to her other than a public funeral. He also says that “he has not paid anyone, not even one of her legates.” The Senate, on the other hand, passed a resolution to erect an arch that was to glorify the memory of Livia. Tiberius promised to cover the costs from his own resources. The arch, however, was never built, probably as a result of the emperor’s destruction. Had it been erected, Livia would have been the first woman so honoured. Cassius Dio emphasizes that this distinction has not been “given to women” so far. The senators wanted to repay the empress in this way: many owed their lives to her, and she took care of the senators’ children. A form of honouring her memory was the announcement of a year of mourning, obligatory for women. Livia’s ashes were placed in the Mausoleum of Augustus.

Tacitus writes: “Her funeral was modest, her testament lay unfulfilled for a long time. A eulogy from the tribune in the forum was delivered by her great-grandson Gaius Caesar [Caligula], who later ascended the throne.” He emphasizes that Tiberius did not take part in the last ministry, which he justified with important matters. Tacitus is very critical of Tiberius’ behaviour. He emphasizes that he has not changed his lifestyle. He did not allow the Senate to grant too many honours to Livia. The senate’s attitude is best illustrated by the words: “As long as Augusta was alive, there was still someone to turn to, especially since Tiberius had an ingrained respect for his mother, and Sejanus did not dare to overtake the mother’s seriousness. Now both of them, as if released from the curbs, gained momentum”. Earlier, Tacitus accused Livia of wanting to share power with his son, he attributed the worst deeds to her, and now he praises her. He emphasizes that she was the only person Tiberius respected and that she helped more than one senator to protect them from imaginary accusations.

From the account of Suetonius, we learn that Tiberius did not visit his mother during her illness. After her death, “he caused a delay in the funeral for many days until finally, the body began to decay and rot.” He then had her will annulled. All her friends, whom she asked to take care of her funeral, suffered hard: “He assigned one of them, the knighthood, to pump water”.

Tiberius’ attitude towards Livia is downright reprehensible. Her death showed that he was devoid of any feelings towards his mother. And, after all, he owed his throne to her, not only as a result of the intrigues and assassinations she supposedly inspired but above all the fact that she was his mother, Augustus’s wife. Only that could make him emperor. He would not have been if Livia had stayed with her first husband. He would be nothing if not for Livia’s marriage to Augustus. And yet his respect for his mother ends with her death, or rather his fear of Livia ends then.

Cult of Divine Augusta

The process of Livia’s deification was very long and complex. In the sources, we find a clear message about Tiberius’ reluctance to deify Livia. Suetonius and Cassius Dio clearly write about it. The former points out that Tiberius forbade worshipping her as a god, “allegedly referring to her own will”. According to Cassius Dio, the emperor “expressly forbade her being placed among the gods.” In turn, from Tacitus and Suetonius we learn about the clear inhibition by Tiberius of the senate’s initiatives to honour the memory of Livia. He did not agree to the implementation of her testamentary provisions.

We don’t know Claude’s motives. Just as we don’t know why Tiberius, her son, and then Caligula didn’t. The latter gave a eulogy in her honour after her death. In addition, Caligula, already during his reign, “paid out the records from the will of Julia Augusta, the execution of which was suspended by Tiberius”.

The apotheosis of Livia was carried out by Claudius. The novel and the film motivate his action with a promise to the dying empress. For a modern historian, however, there is no doubt that Claudius was guided by dynastic considerations, that is, issues of legitimizing his power. All rulers until now obtained it through their direct relationship with Augustus. And Claudius had quite distant ties to him. Tiberius was not only the son of Livia, but also, thanks to the adoption of Augustus. Claudius, on the other hand, was only the grandson of Livia, and nothing but her tied him to the imperial throne. Livia was a politically important link here. It is in this context that Claudius’ decision to deify Livia should be considered. This event was one of the most important propaganda acts during the reign of Claudius. The apotheosis of Julia Augusta took place on January 17, 42, the same day as the wedding of Livia and Octavian in 39 BCE. The allusion was clear. Of course, Claudius commemorated this event with a series of coins, showing the head of the divine Augustus on the obverse with the inscription DIVVS AVGVSTVS, while on the reverse we see a seated Livia and the inscription DIVA AVGVSTA. In the right hand, the new goddess holds an ear of corn and a poppy, in the left a torch, which identifies her with Ceres.

As we already know from Cassius Dio, Livia rested in the Mausoleum of Augustus, where her statue was placed and the Vestals were ordered to make sacrifices. Sources repeatedly describe Livia’s relationship with the Vestals. In the times of Augustus, the Vestals became an important congregation, they were the most dignified priestesses. Because of these ties with Livia, they were ordered to take care of the cult of Julia Augusta. No other women’s college dedicated to the divine Augusta could give her such splendour as the care of the Vestals. All women were ordered to take oaths in the name of the divine Augusta.

The cult of Julia Augusta – Livia, was a kind of continuation of the cult of Augusta, its complement. The reason why Claudius decided to deify Livia could also be, in addition to the above-mentioned reasons, hope for his own apotheosis. After all, he was now the grandson of the divine Julia Augusta.

Livia was the first empress of Rome. The most controversial of all the next. Her strength of character and the role she played at Augustus’ side caused Tacitus, Suetonius and others to perceive her as an imperious person devoid of any feelings. She wasn’t the type of woman everyone was used to. In addition, she was the wife of Emperor Augustus. She departed from the standards to which Tacitus was accustomed. She wasn’t a grey mouse hiding in her rooms. On Augustus’ side, she played an active role and did not hide it. She had to be reckoned with. This aroused various assessments and even reluctance and hatred for this type of woman.

Imperium Romanum is not only crimes and intrigues, it is above all life in a society very different from ours. Morally incomprehensible to us, but with its own style and charm. Livia in this society seemed to stand out, she was the future. A new, liberated, intelligent woman who for many men of the time could be a threat to their ideal male world.