Chapters

The Roman state, during its five centuries of existence, conquered the entire Apennine peninsula, and its last victim was the Etruscan city of Volsinii in 264 BCE. The same year, Rome came into conflict with another power in the Mediterranean – Carthage, which caused major changes in the administrative structures of the state – namely the creation of the first province.

First Roman Province – Sicily

As a result of a long war (the so-called First Punic War), which lasted until 241 BCE, Rome captured three islands at the expense of Carthage: Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica. Sicily (Sicilia) – with the exception of a few cities that gained autonomy (e.g. Syracuse, Messana, Segesta, Panormos, Centuripe) – became Rome’s first province in CE 241, with the other two islands becoming part of another in 225 BCE, known as Corsica et Sardinia. Being a province meant submitting yourself (deditio) to Rome.

The first move against Sicily was to start collecting a tenth of the harvest tribute. Then a praetor was appointed for the residents and a separate one for the newcomers. It was not until 227 BCE that a praetor was appointed for Sicily to oversee relations between the Romans and the locals. He was elected by committees and additionally received financial support from quaestors. This type of provincial organization became a model for successive acquisitions.

Roman provinces

The province incorporated into the Empire was determined by an appropriate act (lex provinciae). The same document regulated the situation of the individual towns within the province. Some of them were provided only by the army, others did not pay taxes or had their own judiciary. In short, the law: (1) divided the province into regions; (2) establish taxes and designate tax districts; (3) it divided the province into judicial units; (4) defined the relations between the senate, officials and assemblies. Unregulated matters were supplemented with the edicts of the governor.

The main task of the province was to keep Rome, or rather the Roman people, which was most often manifested in the so-called grain levy. The townspeople were also obliged to pay taxes.

It should be noted that the word provincia meant a certain range of powers of attorney of an official that had been entrusted to him.

Governorship during the Republic

The election of the governor during the republic was made from among the former consuls or praetors (the so-called proconsuls or propretors) by lot or by appointment of the Senate. It should be noted, however, that the election to the office had no legal support and the election could have been blocked by the Roman congregation. Typically, senior officials took over the governorship of the provinces in which they operated or were not fully conquered and required their continued involvement.

Due to their inferior position in relation to consuls, the procurators usually received “little problematic” provinces, which did not require large powers from the official. However, it was not a rule and there were exceptions. By contrast, proconsuls usually received peripheral provinces that were vulnerable to attacks or required a permanent military detachment. Consuls were often responsible for provinces that were still not fully conquered.

Duties of governors

The duties of Roman governors can be divided into four categories:

- The governor was the highest judicial authority in the province. He could have ordered the death penalty; moreover, the most important things were happening only before him. It was possible to appeal against the governor’s sentence only in Rome before the praetor or later the emperor; of course, however, the journey had to be taken into account, and therefore a considerable cost.

- Both proconsuls and prophets, taking the office of governor, had imperium, that is the right to command an army. Their authority was confirmed by their accompanying liqueurs: the proprietor was entitled to 6; to the proconsul, either the 6th or the 12th. During the Empire, the less important provinces had auxilia troops as garrison; the border and security-relevant provinces of the Empire had legions. The military forces were supposed not only to protect against external threats but also to suppress all revolts and ensure the maintenance of stable power and public order.

- The governor, as a representative of the Senate, supervised the collection of Rome and its citizen’s taxes from the provincial inhabitants. Lower local authorities and private entrepreneurs, the so-called publicani. Sometimes, in order to improve the financial situation, it was decided to release new coins or transfer funds from public institutions, such as: temples.

- The governor also supervised finances, construction, kept order and ensured good communication within the province.

In his rule, the governor relied on the help of officials who were referred to as comites. Depending on the complexity and the level of importance of the tasks, the governor’s court could have been proportionally larger. Governor’s assistants dealt with specific issues and included particular ministries.

In addition, in really important provinces, the governor could count on the support of quaestor, who was delegated from Rome to supervise finances and sometimes even command the army. Sometimes, depending on the needs, the governor could also allocate small portions of the provinces for administration/control to prefects, prosecutors, or legates (legati).

Abuses of governors

The ambitious politicians of Rome, wanting to achieve glory and high social position, very often used corruption and bribes to take up new positions. For this purpose, they often got into debt. It was no different with taking the office of governor. Connections and bribing senators allowed politicians to take over the management of truly rich provinces. As you might expect, collecting taxes was quite a lucrative activity, which often led to abuses. The inhabitants of the province were forced to pay large taxes and bribes to the governor so that he could pay off his debts and accumulate private fortunes. To prevent this from happening, in 149 BCE under Lex Calpurnia a tribunal was established for the acceptance of bribes by officials (queationes perpetuae de rebus repetundis).

In practice, however, the governor’s power, for the duration of his mandate, was practically unlimited in the province, and for possible offenses, he was rarely affected by consequences. This was due to his imperium which guaranteed immunity from the courts. However, after leaving office, provincial representatives could file a complaint on behalf of their compatriots and bring a lawsuit against the governor. A great example is the trial of the governor of Sicily, Verres.

Trial of Gaius Verres, governor of Sicily

The trial of Gaius Verres, governor of Sicily for fraud in 70 BCE is the best described and source-presented event showing the degree of corruption of Roman officials and the use of provinces for their own selfish needs and the desire to get rich.

Most of the information about Verres himself and his trial comes from the preserved letters and accusatory speeches of Cicero. No notes or notes have survived from the defense side. Naturally, this raises the suspicion of a one-sided depiction of history, but even apart from many dubious claims of Cicero, it is certain that Verres was an example of a man corrupted and exploiting the inhabitants of Sicily on a large scale.

Sicily was an important Roman province that provided the state with enormous grain supplies and was sometimes referred to as the “storehouse of the empire.” The assumption of the governorship of Sicily by Gaius Verres in 73 BCE was a real ennoblement, and for him himself a great opportunity to get rich. During the three years of his rule, Verres, in line with Cicero’s speech, committed the following offenses:

- abuse of judicial powers and unlawful sentences;

- enforcement of agricultural taxes;

- confiscation of works of art and private and public goods;

- mismanaged fleet.

In the case of judicial abuses, Verres showed real disrespect. He ordered to pay himself bribes if he wanted to obtain a favorable sentence; he intimidated judges during the trial, he also threatened them with death; falsified court records, the number of witnesses; ordered to give false testimony; decided about the choice of priests. Moreover, Verres ordered the Sicilian cities to set aside money to build public statues. The part of the money that was not used was transferred to the private account of the governor.

The trial was Cicero’s “springboard” on the political scene. Cicero, leading the case and leading to the conviction of Verres, won a great victory that allowed him to obtain the title of the greatest orator and lawyer of Rome. This event also gave him a chance to develop his political career: in 66 CE he became a praetor, and in 63 BCE he became a consul. It was a great achievement for a man who did not come from the senatorial circle, the so-called homo novus (the “new man”).

According to the verdict, Verres was forced to go into exile in Massalia, where he died after 27 years. Some of the valuables he had stolen went with him to southern Galli.

Governorship during the Empire

With the successive conquests of the Roman state, the number of provinces at the head of which officials had to sit grew. To this end, in 52 BCE, Pompey the Great passed the law of Lex Pompeia de provinciis, which required former praetors and consuls to assumption, five years after the end of his office, to the governorship of the Roman province.

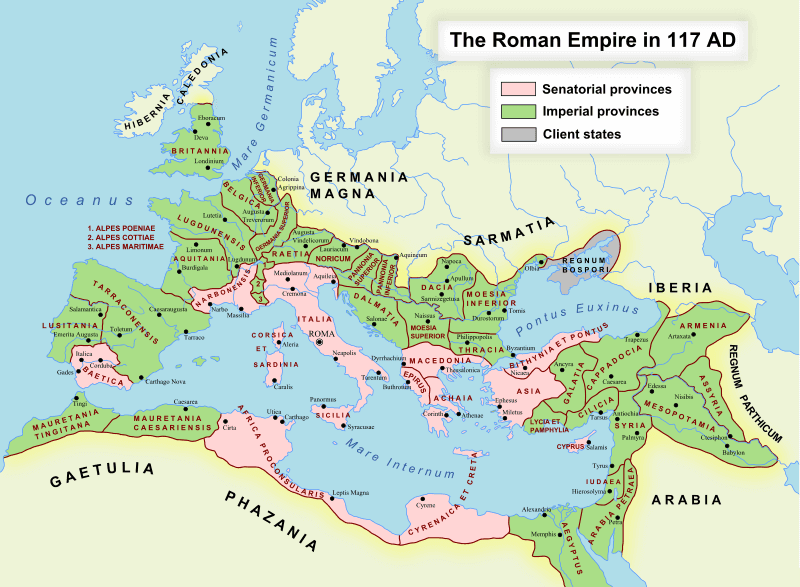

With Octavian Augustus ‘ victory in the civil war over Mark Antony and Cleopatra in 30 BCE there was a transformation of the Republic into the so-called Pryncypat. August concentrated in his hands most of the offices and titles that guaranteed him a priority in the state while maintaining the appearance of the continuity of the former system. In order to secure his position, Augustus divided the Roman provinces into two types:

- imperial provinces – provinces where the nominal governor (in the rank of proconsul) on behalf of the senate and the Roman people was the emperor. In practice, the administration of the imperial provinces was exercised by legates (the so-called Legati Augusti pro praetore) who were freely appointed and dismissed by the emperor. These provinces were most often the borders of the Roman Empire; on them, the legions that were under the direct authority of the emperor were stationed.

- Senate provinces – these provinces were owned by the Roman people and were far from Limes. Due to the fact that they were not threatened, they did not require military troops, which was to limit the possibility of the Senate taking power from the emperor. Only Senate had the power to appoint governors (proconsuli).

Division of Roman provinces during the early empire | |

In 14 CE, the senate provinces(provincia populi Romani) were: | The imperial provinces(provintiae Caesaris) were at different times:

|

Governorship during the early empire usually lasted from 1 to 5 years, although there was no rule on this matter.

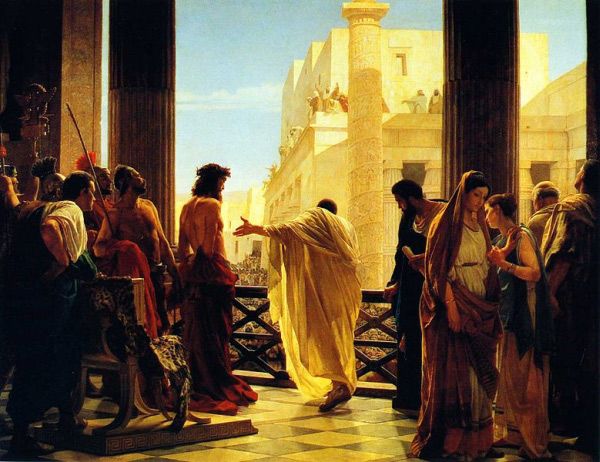

In addition to legates, propretors and proconsuls, the provinces could be governed by the aforementioned prefects, who were originally of a rather military character, e.g. praefectus castrorum(camp prefect). However, due to the mandatum (special task) they could receive additional duties, including civil duties, thanks to the emperor. A great example of a prefect is the famous Pontius Pilate, who ruled over Judea. It is also worth mentioning Egypt, which during the times of the Empire became the private property of the emperor, and his supervision was carried out by trusted people appointed by him. In Egypt, the so-called praefectus Aegypti, who was equine.

It is worth mentioning that since the end of the republic, the equites achieved really high positions in the Roman state. Originally, they were mainly engaged in tax collection, which allowed them to accumulate considerable wealth; however, their ambitions grew over time, which led, for example, to the elevation to the throne of Vespasian, who came precisely from the equite state.

In time, some governors of the provinces were called procurators (procuratores), who had only civil power. Their duties began to be limited to tax collection (three times a year), maintaining public order and exercising judicial power. The army was in the hands of legates and other commanders.

Governorship during the late empire

With the assumption of power by Diocletian in 284 CE, there is a new period in the history of the Empire, when full power is concentrated in the hands of the emperor and the Senate loses all influence – the so-called. dominate.

This emperor was also famous for dividing power between four rulers who had a different area to control. It was the so-called tetrarchy, which in Greek means “rule of four”. The decision to separate responsibility for given regions resulted from the need to act quickly in the face of growing problems in the huge Empire. The tetrarchy did not formally divide the territory of the empire between the rulers, each of them was the emperor of the entire empire, but the tasks assigned to them concerning specific areas:

- Diocletian, Augustus of the East, controlled the lands of Asia and Egypt, his capital was Nikomedia;

- Galerius, Caesar of the East, controlled the Danube area, mainly from Sirmium on the Sava;

- Maximian, Augustus of the West, dealt with matters of Italy, Africa and Spain, first from Aquileia and then from Milan;

- Constantius, Caesar of the West, looked after Gaul and Britain from the capital of Trier.

In addition, in 293 CE Diocletian began an administrative reform which was finally completed by Constantine I in 318 CE. The reform involved the separation of 12 dioceses (from the Greek word dioikesis, meaning “jurisdiction”), each containing several provinces that were governed by vicars (vicarius) of the equite estate. The provinces were now also called eparchies (Greek), and the governors governing them had different names: proconsul, corrector provinciae, moderator provinciae or praeses provinciae.

During the independent reign of Constantine (324-337 CE) another function was allocated – dux – army commander, mainly in the border provinces. Even troops from several provinces could be under his control. For military operations in the field, comesa was in command, soon replaced by magistri militum – powerful influences in the late Empire.

As you can see, there was a clear separation of civil and military power, which was intended to protect against further revolts of ambitious politicians, as was the case in the 3rd century CE.

Constantine I further administrative division and created three prefectures:

- Gaul

- Italy, Africa and Illyria

- East

Each was governed by the praetorio prefect appointed by the emperor. The prefect was the superior of vicars and provincial governors and was directly subordinate to the ruler. He was in charge of the judiciary, finances and tax collection of the prefecture.

Assumption of office by a governor in the late empire

From the 2nd century CE, there was a norm that forbade a person born in a given place to govern a province. Its application also took place at a later time, but it seems that the letter of the law could be omitted or simply dead. Interestingly, during his mandate, the governor could not leave the province.

There were no educational or skill requirements for the candidate. To a large extent, the main role was played by the position of a person in the Empire, the trust the emperor had in a given person, or possibly favorable opinions among advisers about him. Very often the governorship was also obtained as a result of recommendations (suffragium). Here it was important to have some kind of patron or trusted man; bribes were also an inseparable element.

The governors had different titles: praesides, correctores, consulares or proconsules, with the first having the lowest rank and the last the highest. However, other terms appear in scientific works and sources: moderator, rector or index ordinarius. Depending on the rank, they were entitled to remuneration: (1) either in the form of grain (annona), fodder (capitus), other products (cellaria); (2) or in the form of gold. Of course, apart from the salary, the governor could personally improve his finances through additional fees or bribes and the separation of lower offices.

There were no clear requirements for the governor’s term of office; however, known contemporary research suggests that the average management board-lasted two years. It seems, then, that the governor lost importance in relation to the early empire; proof of this thesis is the fact that the governors lost – with the reforms of Diocletian and Constantine – the right to command the army, and their activities focused only on the civil aspect. Duties focused mainly on supervision of the judiciary (both civil and criminal cases) and tax collection (in products and money). In the case of the judiciary, the governor’s judgment could be appealed against to the prefect or vicar, or even the emperor. Governors were also ordered to collect taxes legally and not oppressively. All actions towards the population were controlled by senior officers – here various names appear: palatinii, canonicarii, tractatores or compulsores. Extortion and ineffectiveness were punished.

The governor’s seat was located in praetorium, where there was also a courtroom, office, archives and a prison. An inseparable part of the governor’s work was the visit and control of individual towns in the province.

While fulfilling his functions, the governor largely relied on the local elites with whom he had to maintain regular contact. A great example are the letters (almost 1500 have been preserved) of Libanius – orator and philosopher from Antioch from the 4th century CE – which are a real treasury of knowledge about life in those times, especially in Syria. His writings bear witness to how this world was like ours today; for example, Libanius repeatedly describes attempts to “settle” certain things for acquaintance, correspondence with successive governors of Syria.

The governor’s office

The office of governor (officium) was responsible for many things. On average, one hundred people worked in the office, but in the case of larger provinces this number could have been much higher. The office housed, among others:

- cornicularius – personal secretary of the governor;

- adiutor – responsible for announcing the governor’s decisions;

- commentariensis – responsible for the legal sphere, including prisons and criminal matters;

- ab acta – supervision of judicial documentation;

- a libelli – correspondence;

- numerarii – tax collection in money;

- tabularii – tax collection on products.

Provincial officials were not subject to replacement and in practice, it depended on how efficient the administrative policy of the state was.