The only ancient source of information about masks that were used in ancient times during theatrical performances is Julius Pollux, a Greek scientist from the 3rd century CE, who wrote the work Onomasticon. In his work, he lists a total of 44 different comic masks that could be used during the performance.

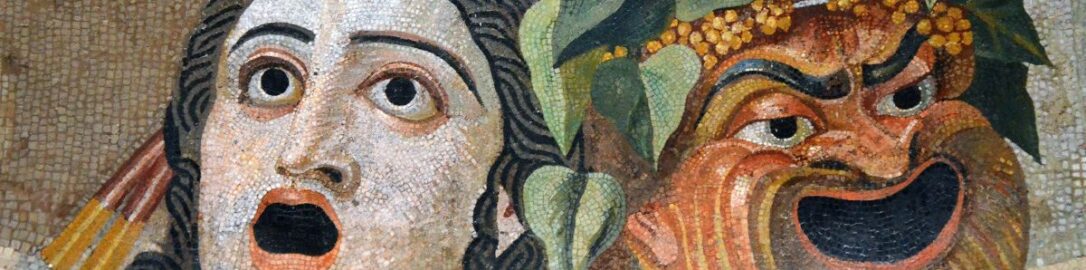

A large amount of information and a general idea of what theatrical masks looked like in ancient Greece and Rome are provided by the preserved ancient artefacts, on which we find the reconstructed appearance of the actors’ equipment. During the day, we discover oil lamps in the shape of theatrical masks or cameos with engraved masks. No strictly theatrical masks have survived to our times; this is due to the fact that they were made of organic materials that had virtually no chance of surviving.

Antique masks were certainly beautifully decorated and very colourful, which only intensified the perception of the actor’s performance, whose mask reflected daylight. It should be recalled that, unlike contemporary theatres, in ancient times this type of facility was open, and the sun helped in creating the right spectacle.

According to the latest research (including from 2007 by a team of researchers under Dr Amy R. Cohen), in large and open theatres, both the shape of the object and the masks themselves enhanced the actor’s voice. As it turns out, the masked actor had a clearer voice when speaking in a lower pitch. It should also be noted that the size of the mask and the distance from the actor’s face made the voice resonate. What’s more, the mask allowed viewers to better hear the actor’s voice without having to point directly at them. For example, an actor with his back to the audience section, if not wearing a face mask, was barely audible or not heard at all.

Aristotle said that an effective actor is one who has a loud, harmonious and rhythmic voice. As it turns out, the masks were not only visual but also acoustic.