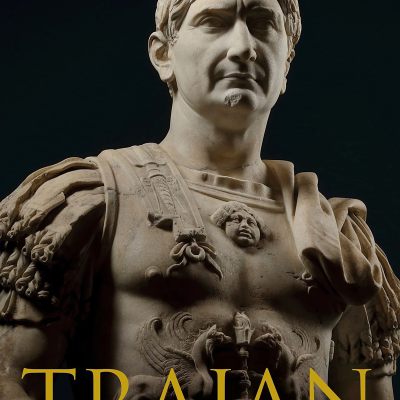

The book “Trajan: Rome’s Last Conqueror” by Nicholas Jackson is, as the title suggests, describing the life and achievements of one of the greatest Roman emperors, during whose reign the Roman Empire achieved the greatest territorial reach in history. The book was published by Greenhill Books.

Nicholas Jackson was unknown to me before and, as I read about him, he is not a historian. Jackson is a pharmaceutical and medical practitioner, apparently treating his passion for Roman history as a hobby. The author also has no other historical publications in his oeuvre, which made me fear that, unfortunately, the content of the book may not meet the basic requirements. As it turned out, my doubts were quickly dispelled. As said in the introduction, the author spent several good years writing the book; including the collection of materials and their analysis. He consulted with the eminent historians Anthony Birley and Barbara M. Levick. The essence of Nicholas Jackson’s work was a credible presentation of Trajan as a man, leader, emperor, and a clear indication of what can be considered fiction and the truth of the messages. The author tries to approach the information in a critical manner in the book, an example of which can be, for example, the analysis of Trajan’s death and unclear information as to the transfer of power to Hadrian.

From my perspective, an extremely intriguing aspect of Trajan’s biography was the issue of presenting the relationship with Hadrian, who was in no way particularly favoured during Trajan’s lifetime. When in 86 CE, then 10 years old Hadrian lost his father and mother, the later emperor Trajan and Publius Acilius Attianus (later Trajan’s praetorian prefect) decided to look after him. With his accession to the throne in 98 CE, Trajan could look for a real heir in Hadrian, but the failure to hand over high titles and offices to Hadrian suggests that Hadrian was not in the special favours of the emperor. Certainly, a great honour for Hadrian was the consent to his marriage with Vibia Sabina (who was then 12 years old) – the granddaughter of the emperor’s sister; it is possible, however, that the consent to the relationship resulted from the persuasion of Plotina herself – Trajan’s wife. As it turned out, however, the relationship was not successful, partly due to Hadrian’s homosexual tendencies.

But where does Trajan’s dislike of Hadrian come from? The author believes that it grew gradually and could result from the defiant and disobedient youthful behaviour of Hadrian, which displeased Trajan, known for his modesty and moderation. Moreover, the information coming to his ears about the unsuccessful relationship between Sabina and Hadrian certainly limited Hadrian’s promotions. After Trajan’s death, Hadrian, possibly with the help of Plotina and Attianus, secured his power, one of his first decisions being to accuse four of Trajan’s important advisers of conspiring and killing them.

Naturally, the author does mention in the book Trajan’s adolescent years (about which we do not know much), his origin, familiarization with the military, a career in the army, and finally the process of coming to power. Trajan is shown to us as a competent person who, in his decisions, is based on the advice of his trusted consilium, and among his relatives are: his wife Plotina, older sister Marciana and friend Sura. The description of the emperor’s relationship with his wife, who was rather a companion, and the emperor himself had homosexual preferences, seems to be extremely interesting.

Certainly, the descriptions of Trajan’s war campaigns in Dacia and Parthia, which the author additionally supplemented with the proposed lists of commanders, units and the number of the army, are of great value in the book. At some point, there appear some author’s reflections on Trajan’s identification with Alexander the Great, a figure who for many people of antiquity was an unattainable ideal and model of a winner.

To sum up, the Reader receives a total of 250 pages of substantive content, which has been enriched with numerous footnotes (unfortunately at the end of the book), a broad bibliography and an index. The author created great work, relying on multiple valuable ancient and contemporary sources, and managed to conduct a thorough analysis of Trajan’s life, about which, incidentally, we do not know as much as we should know. Our primary sources of knowledge about Trajan are the preserved works of Cassius Dio, Arrian or the letters of Pliny the Younger.

In addition, in the middle of the book, you will find many beautiful illustrations, photos and maps related to Trajan’s life, which allow you to better find yourself in the ancient world.

Certainly, the book is recommended for anyone who would like to learn more about the great Emperor Trajan, and is looking for reliable and good studies; a great edition of the book is an additional value of the publication.