Pantheon seems to be a perfect building – entire volumes have been written about the perfection of its dome. Next: about the proportions of its rotunda. When we stand close to a temple, we usually do not pay attention to certain irregularities in its shape. Yet some experts note that during the construction of the Pantheon, not everything probably went according to the architects’ intentions.

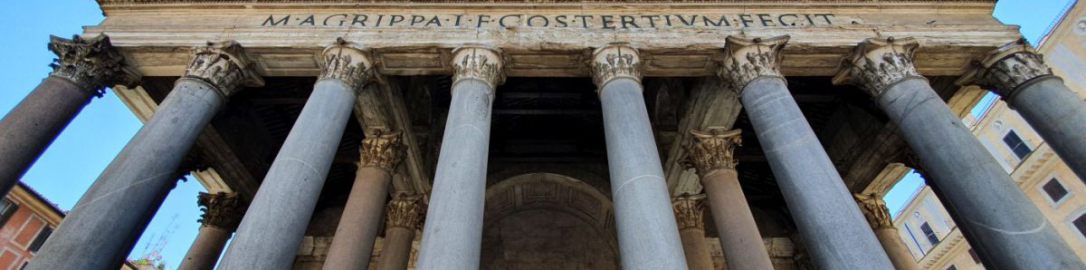

16 columns were used to build the Pantheon’s portico – each carved from a single block of stone, each imported from the quarries of distant Egypt, each approximately 12 meters high (without base and capital). Together they create a monumental pronaos preceding the entrance to the rotunda. The portico seems to fit perfectly into the entire building. But all you have to do is move away a little or look slightly from the side, and certain doubts begin to arise.

Let’s start with proportions. In Greek and Roman architecture, proportions were very important. Both the Greeks and the Romans rarely introduced new forms into architecture and focused on improving the proportions of previously used forms. When we read the work of the Roman architect Vitruvius, we are surprised by the detailed calculations of the proportions of the temples. Nothing was left to chance there: the height of the columns, their thickness, the space between the columns, the size of the bases and capitals, the size of the architraves above the columns. Attention was even paid to make the extreme columns a bit thicker than the central ones, because centuries of experience had taught architects that the human eye tends to “slimmer” the extreme columns. Meanwhile, when we look at the front of the Pantheon from a distance, the portico seems strangely disproportionate… It is wide and relatively low, giving the impression of being squat… When we compare it with other well-preserved Roman temples – e.g. Portunus on the Tiber, Maison Carrée in Nîmes in France, Augusta in Pula in Croatia or the temples forming the Capitol in the Tunisian city of Sbeitla, the disproportion becomes clear. They can be partially explained by the fact that the portico of the Pantheon consists of as many as 8 columns in one row, and the other temples I mentioned only have four or six. The impression of squatness can also be explained by a different perspective – after all, the ground in front of the Pantheon has risen so much that today, standing at the northern end of Piazza della Rotonda, we see the icon of Rome slightly from above, while the ancients saw it from below.

Is it possible that the architects of the Pantheon deliberately designed the front portico to be more expansive? Considering the importance they attached to proper proportions, this would be very strange… What I call squatness or spread is described much more bluntly by the famous antiquity researcher Mary Beard: “(…) certain clumsy features of the finished building lead us to assume that Hadrian’s architects counted for the supply of twelve columns fifty feet high, but they had to change the design at the last minute (…)” (SPQR History of Ancient Rome). I won’t go into why the author mentions twelve columns when there were sixteen of them, because it doesn’t matter here.

If we look at the Pantheon slightly from the side, we will see a triangular mark on the wall behind the sloping roof of the portico. According to some researchers of the Pantheon, it is this mark that determines the originally designed height of the front portico. To achieve it, columns would have to be as much as ¼ higher than those that ultimately decorated the front of the temple.

It cannot be denied that if the portico were higher, the whole thing would seem much slimmer. If this was indeed the original plan, why was it changed? The most common explanation is the enormous weight of the columns. Carving and bringing huge pillars from quarries in the Egyptian desert was a huge and complicated undertaking. The above-mentioned Mary Beard simply states that the design was changed because the quarry was unable to supply so many such large columns.

Certainly, delivering nearly 15-meter-high pillars to the construction site was a huge challenge. And it wasn’t just about the problems of transporting them from Egypt. The difficulty was, for example, delivering long blocks of stone through the narrow and winding streets of densely built-up Rome. Somewhere I came across a mention that sometimes the street pavements collapsed under such a heavy load and the slabs covering the sewage system cracked.

Was it impossible for the Romans to deliver 15-meter-long columns to the Campus Martius? I have my doubts. After all, the Romans had already brought comparable monoliths to Rome, and even much larger ones. The Egyptian obelisks erected by Octavian Augustus were approximately 21 and 24 meters long. Obelisk of Caligula: over 25 meters. Bah! Even when the empire weakened greatly in the 4th century AD, Emperor Constantius II managed to bring to Rome from Egypt an obelisk 32 meters high (!) and weighing between 400 and 500 tons! – which is several times heavier than the columns that were supposed to stand in front of the Pantheon!

So were logistical problems really the reason for lowering the Pantheon’s portico and disturbing its proportions? Or maybe the explanation lies elsewhere?

Recently I came across a book titled: “Roman builders. A Study in architectural process” by Rabun Taylor, which provides a detailed analysis of the entire construction process in ancient Rome. The author pointed out that the problem was not bringing the large columns to Rome, but lifting them and placing them in the right place. Someone might say that after all, the large obelisks were somehow able to be erected, so why were the columns a problem? It turns out that there is an important difference: obelisks were usually placed in an open space in which a huge scaffolding, a system of blocks and winches capable of lifting weights of up to several hundred tons could be placed. Without the cranes we have today, the column relied entirely on human power: the column was placed horizontally on the ground next to where it would stand, and then slowly lifted up using blocks and rigging on a massive wooden scaffold. The most important thing, however, is that hundreds of men turning the winches to pull the ropes had to be positioned on the opposite side from where the column was mounted. The author of the mentioned book analyzed all possible starting positions of the columns on the ground during the construction of the Pantheon. Lifting them required placing them on the ground diagonally on the rotunda side and placing scaffolding, turnstiles and people to operate them on the opposite side, i.e. in the square. The opposite action (columns on the ground on the side of the square, and scaffolding and workers on the side of the rotunda was out of the question, because the construction of the Pantheon was probably already quite advanced and, judging by the mark on the front wall behind the portico, even almost completed). And here we come to the point: columns longer than 12 meters could not fit between the point of their installation and the rear wall of the pronaos. If the columns were to be even a little higher, it would be necessary to give up the two columns standing right next to the entrance to the rotunda – they would not be able to be placed.

If the theory presented in the mentioned book is correct, it would give food for thought. The lower portico would not have been the result of problems with providing appropriate columns, but a simple mistake made by imperial architects and engineers who overlooked the technical impossibility of placing sixteen 15-meter-tall columns next to the already standing rotunda mass.

Now let’s abandon historical and architectural speculations and let our imagination run wild. We do not know for sure who the architect was who designed the magnificent dome of the Pantheon. However, his work testifies to the genius that the gods gifted him with. The only “celebrity” architect of that time known to us is Apollodorus of Damascus – the creator of, among others, Trajan’s Forum, the baths on Oppius and the great bridge over the Danube. Although this is probably just a guess, it would be completely understandable if the design of the Pantheon was also his work.

According to the conventional wisdom, in Hadrian’s time Apollodorus fell out of favor due to his criticism of the design of the temple of Venus and Roma – supposedly by Hadrian himself. Hadrian, hurt in his pride, had the architect sentenced to exile (and ultimately perhaps to death). What if there was more than just Hadrian’s ego behind Apollodorus’s exile? Or maybe it was an unfortunate architect’s error that made Hadrian, angered by the “awkward shapes” of the Pantheon’s portico, as Mary Beard called them, decide to get rid of Apollodorus? Let us imagine a repentant Apollodorus who stands before the emperor and must inform him that the design of the magnificent portico in front of the Pantheon will have to be changed. That the columns (perhaps already carved, and perhaps even brought to Rome with enormous human and financial effort) will be useless. That the investment will be significantly delayed. And all this because of simple human error. Imagine an angry Hadrian demanding some solution to this problem, and the brilliant Apollodorus this time helplessly throwing up his hands… To erect all sixteen higher columns would require the prior demolition of the newly constructed rotunda and its magnificent dome.

Of course, these are just the speculations of an unfulfilled writer. We will never know what the Pantheon was actually supposed to look like or why the design was changed, nor will we be able to connect this change with Apollodorus’ fate.