Chapters

Marcus Porcius Cato was born in 234 BCE in Tusculum in Latium. He was a speaker, politician, and Roman writer. A talented commander, administrator and statesman. He was called Censor (Censorius), Wise (Sapiens), Ancient (Priscus) or Elder to distinguish him from his great-grandson. His great-grandson was Cato the Younger.

Origin

His ancestors had been farming on Italian soil for many years, which Cato had adhered to effectively.

Porcia family and at the beginning of his political career he was treated as novus homo (“new man”). It was a disrespectful name used by nobles to describe the man who was the first in his family to hold an office that gave him the right to sit in the senate. Cato was cursus honorum aware of his low position from the beginning and knew he had to be ambitious. Due to his later achievements and importance in Roman politics, he began to be recognized as the founder of gens Porcia.

Cato’s ancestors bore only the names of Marcus Porcjus. Plutarch mentions that Cato was the first to start using cognomen Priscus, which was later replaced by Cato – a word for practical knowledge that is the result of natural acumen combined with experience in civil and political matters.

Youth

When Cato was a young man, after his father’s death, he inherited a small estate in the Sabine lands, far from his family home. He describes his youth as a simple life spent: “leading a frugal, hard and hard-working life, tilling the fields, digging up the soil and sowing on Sabina’s stones and boulders”. He spent most of his childhood here hardening his body and mind, studying agriculture and economics. Near his land, there was a hut in which lived a certain Manius Curius Dentatus, who, despite having three triumphs, decided to lead a modest and upright life. The person of Dentatus was forever remembered by the young Cato, whom he wanted to imitate at all costs.

In 217 BCE, like many his age, he entered the military and participated in the Second Punic War. There are some discrepancies among historians about this period in Cato’s life. In 214 BCE he was to serve in Capua. At the age of 20, he was to become a military tribune in Sicily and serve under the dictator of Fabius Maximus in Campania. He fought for Tarentum in 209 BCE. Two years later, under Claudius Nero, he travelled north to Lucania to assess the forces of Hasdrubal Barkas, Hannibal’s younger brother. Apparently, Cato’s actions contributed to the victory of the Romans in the Battle of Metaurus and in capturing Hasdrubal. Cato’s skills allowed him to climb the military ladder in a short time and then gain clerical positions.

During the war, Cato found time to go to his estate, where he also devoted himself to monotonous agricultural work. He dressed modestly and, in the opinion of his neighbours, was an example of a good host. Over time, Cato began to participate in local mediations, sometimes before recuperatores (judges in the public interest), which allowed him to gain confidence and acquire oratorical skills. It is worth presenting a description of Cato’s figure according to Plutarch in “The Life of Cato”:

He tells us that he never wore clothing worth more than a hundred drachmas; that he drank, even when he was praetor or consul, the same wine as his slaves; that as for fish and meats, he would buy thirty asses’ worth for his dinner from the public stalls, and even this for the city’s sake, that he might not live on bread alone, but strengthen his body for military service; that he once fell heir to an embroidered Babylonian robe, but sold it at once; that not a single one of his cottages had plastered walls; that he never paid more than fifteen hundred drachmas for a slave, since he did not want them to be delicately beautiful, but sturdy workers, such as grooms and herdsmen, and these he thought it his duty to sell when they got oldish, instead of feeding them when they were useless.

– Plutarch, Life of Cato the Elder, 4, 4-5.

The lands surrounding Cato’s estate belonged to Lucius Valerius Flaccus who came from a well-placed patrician family. Like Cato, he was a supporter of the strict and old Roman traditions, the origin of which dates back to the Samnites. He was opposed to Greek and Eastern civilizations, which were directed at luxuries rather than rules-based living. Flaccus, as a forward-looking politician, was looking for a young and energetic man to support his policy. He appreciated the courage and oratory skills of Cato, which in his opinion were to serve the good of Rome. Flaccus decided to support the young politician.

Political career

In 205 Cato was appointed a quaestor, and a year later he officially took office in Sicily. Cato’s main task was to look after the finances of the island. In addition, Cato, as wished by the Senate, had to contribute to the organization’s mission Publius Cornelius Scipio, the later winner of Zama, to Africa. According to ancient historians, there was no clear friendship between the two Romans.

In 199 BCE Cato assumed the office of the Edile and with his companion, Helvius restored ludi Plebeii (held November 4-17), which involved theatrical performances (ludi scaenici) and athletic competitions. Moreover, on this occasion, they held a great feast in honour of Jupiter. In 198 BCE Cato became praetor in Sardinia. There were 3,000 infantry and 200 cavalry under his command. Here, for the first time, he was able to implement his strict rules. He cared about public morality, limited provincial expenses (e.g. religious ceremonies were held in moderation), introduced order in the jurisdiction (the principle of impartiality), and expelled moneylenders. The rebellion that took place before Cato took office, according to the memoirs of Aurelius Victor, was completely averted.

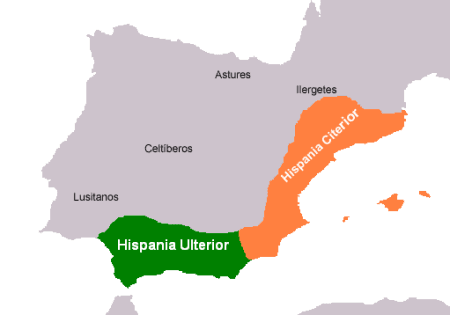

In 195 BCE Cato became a consul with his patron and friend Flaccus. That year, he opposed the abolition of lex Oppia, a law against women’s luxury, introduced in 215 BCE through the plebeian tribune of Gaius Oppius. The law was introduced at a time when Italy was plundered by Hannibal and the treasury was empty. Through this act, they wanted to repair Rome’s finances. However, with Hannibal’s defeat, women began to demand the abolition of lex Oppia, which was sought by many officials and politicians. The matter was very sensitive, and even Flaccus hesitated quite significantly about the idea of abolishing the law. But Cato was adamant, making a series of blunt speeches against Roman sumptuousness. Ultimately, the law was abolished, and the women made a procession along the city’s roads, displaying their expensive ornaments. Although Cato’s behaviour was criticized, it did not prevent him from taking command of the army in Nearer Spain (Hispania Citerior).

In Spain, Cato’s task was to lead a campaign against the disobedient Iberian tribes, which he eventually successfully defeated. Cato himself later claimed that he had demolished more cities than he had spent days in the war. Cato was tirelessly vigilant and worked hard. He shared the labour of war with his soldiers, eating and sleeping as they did. During the battle, he proved to be a good tactician and military man. During the fighting in Spain, Cato ordered a coin to be minted with the words “Bellum se ipsum alet” (“The war feeds itself”). It was Cato’s response to Rome’s proposal to provide supplies for his army in Iberia.

When Cato was able to clear the land of rebels, his next step was to improve the administration of the province. Its main goal was to increase Spain’s revenues by increasing the production of iron and silver. The Senate, in exchange for Cato’s successful campaign, instituted a three-day thanksgiving ceremony. Finally, in 194 BCE, Cato had a triumph, during which Rome was shown enormous amounts of brass, gold, and Spanish silver.

During his reign, Cato had to deal with a series of attacks on himself, mainly from the Scipio family. However, his actions proved that he is an efficient and reasonable politician, manager and commander.

The military career did not end with the campaign in Spain, however. In 191 BCE Cato was elected a military tribune (some historians speak of a legate) under the command of consul Manius Acylius Glabrion. The consul overtook Antiochus III during the so-called Syrian War (192-188 BCE); then he went to Greece and defeated the enemy at Thermopylae, which resulted in the withdrawal of Seleucid troops to Asia Minor. Cato took part in the expedition, who once again proved his qualities.

Cato’s reputation as a soldier was already secured, so he decided to return to Italy and oversee the state’s public interests. He controlled, inter alia, candidates for state office and was personally involved in accusing, inter alia, such personalities as: Scipio Africanus or Lucius Scipio Asiatic for corruption. His great success was the destruction of the position of Scipio Africanus, who disappeared from the political scene and died in oblivion.

lex Orchia, a law regulating visitor numbers at entertainment events. In 169 BCE he supported lex Voconia, which was to control the accumulation of undue wealth in the hands of women.

It should also be mentioned that during his tenure in office, Cato had many aqueducts rebuilt, sewage cleaned and fought against the looting of public water by private individuals. Cato also commissioned the demolition of houses that overlap the public roads and the construction of the first basilica in the Forum Romanum, near the Curia.

In 184 BCE Cato reached the peak of his career by becoming a censor. Attachment to republican virtues and Roman tradition earned him the nickname Censor. His hatred towards the Greeks was undying: “When these people give us their literary culture, they will destroy everything, demoralize and make it even worse if they send their doctors here.” Thus, Cato avoided Greek medicine, following the prescriptions of Roman ancestors.

Cato became famous for his irreconcilable hostility towards Carthage and constant calls for its destruction. He accused the Carthaginians of breaking treaties six times between 241 and 219 BCE. His plan to start another Punic war was based on a constant utterance in the Senate at the end of his speech: “Moreover, I advise that Carthage must be destroyed” (Ceterum censeo Karthaginem esse delendam).

Literary works

Cato was also a writer. He became famous as the creator of Latin prose. He wrote, “The Origins” (Origines), a work showing the history of Rome from 753 BCE to 149 BCE, including description of the formation of Italian cities. It was an important source from which Roman historians drew, incl. Salustius and Livy. Few fragments have survived. In addition, he created the song “On Agriculture” (De agri cultura), which is the oldest work, preserved in its entirety, in Latin prose. It is a handbook for running a land estate. It also includes cooking, medical, religious recipes, supply and sales advice, among others. He also created the first Roman encyclopedia, “Maxims addressed to his son” (Praecepta ad filium). It contained information on rhetoric, medicine and agriculture. There are fragments in which he wrote famous sentences: rem tene, verba sequentur – “Stick to the topic and the words will come by themselves”; and “Thieves of private goods spend their lives in chains, thieves of public goods – in gold and purple”, directed at the robbers of the provinces.

He also published his speeches, fragments of which only 80 out of more than 150 have survived. His speeches are characterized by matter-of-factness, compactness and easy use of language. There are: Orationes, De re militari, De lege ad pontifices auguresque spectanti, Historia Romana litteris magnis conscripta, Carmen de moribus and Apophthegmata.

End of life

From 184 BCE, his censor term, to 149 BCE, Cato no longer assumed any office, concentrating only on speaking in the Senate as an opponent of all that was new. In 157 BCE he became one of the emissaries sent to Carthage to mediate a dispute between the Carthaginians and Masinissa, king of Numidia. The mission was unsuccessful and the referees returned home. It was then that Cato saw prosperity in Carthage, which only reassured him that as long as the Carthaginians had their country, Rome would not be safe.

He died in 149 BCE, aged 85, under the consulate of Lucius Marcius Censorinus and Manius Manilius, leading to his dream Third Punic War. It should be noted, however, that some Roman authors, such as Livius and Plutarch, indicate that Cato died at the age of 90.