Ancient times were cruel. The stories recorded in Greek and Roman myths echo the helplessness of people in the face of their surroundings, and the fear of the judgments of the gods symbolizes human weakness in the face of powerful but incomprehensible forces of nature and blind fate. He tests everyone – the rich and the poor, the honest and the deceitful, the virtuous and the dissolute, the humble and the proud. From here it is only a step to the feeling of lack of any agency and simple submission to fate. Especially when the gods put people in an impossible situation…

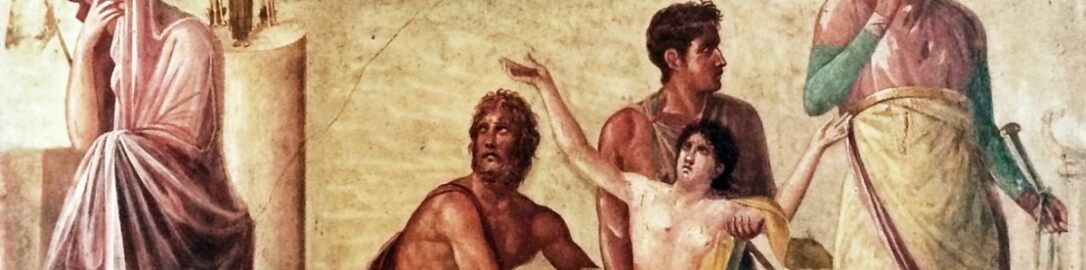

As I have written many times, the Pompeian frescoes are a veritable treasure trove of paintings illustrating Greek and Roman myths. One of them, currently kept in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples, is particularly memorable because, like a few others, it shows a man put by the gods before a cruel and tragic choice. Here it is: on the right, two half-naked men are leading a young woman, and the man on the left is standing with his back turned and hiding his face in his hands.

The painting shows a dramatic moment when the father (the one on the left) decides to offer his own daughter to the goddess Artemis.

The scene illustrates one of the episodes of the Trojan War. You won’t find it in the Iliad itself but in works related to the Iliad. Well, before the capture of Troy, Agamemnon, the leader of the Achaeans besieging the city, received a prophecy that he would win the Trojan War only if he sacrificed his daughter Iphigenia to the goddess Artemis. Every decision was wrong: he had to sacrifice either the life of his daughter or the lives of thousands of soldiers fighting at Troy. The central point of this story, however, is not Iphigenia’s misfortune, but the drama of the leader who stands in front of his army eager for victory, aware that either all of them or his beloved daughter will die. The entire mythical situation is made even more dramatic by the fact that in order to fulfill the gods’ request, Agamemnon ordered his family to come to the camp under the pretext of marrying off his daughter. Completely unaware of her fate, Iphigenia comes to her father with her mother Clytemnestra and brother Orestes, and is happy to meet her father and future husband. But instead of happiness, death awaited her there…

In the Pompeian painting, we see the moment when King Agamemnon made his decision. Despite his wife, he sacrifices his daughter and they lead her to the altar where she is to die. Look at her – she doesn’t look scared. On the contrary: he spreads his arms and looks at the sky. Well, in some versions of the myth, when Iphigenia understood the will of the gods, she accepted it and was ready to sacrifice herself for a great cause. But even the daughter’s acceptance of her fate does not alleviate her father’s pain. That is why Agamemnon, on the left side of the fresco, turns helplessly in despair, so as not to see what is about to happen. On the right is the seer Calchas, through whose mouth Artemis demanded a sacrifice. Artemis and her brother Apollo look down on the situation.

The Pompeian painting is inspired by the work of the Greek master Timantes from the 5th century BC. His “The Offering of Iphigenia” painted on board delighted with the perfect rendering of the emotions on the characters’ faces: sadness in Calchas and Odysseus, despair in Ajax, and grief in Menelaus. According to the Roman historian Pliny the Elder, who gave us information about the greatest names of ancient painting when creating “The Offering of Iphigenia”, “the artist painted everyone else as grief-stricken, especially his uncle, and having exhausted all possibilities of representing mourning, he covered his father’s face because he could no longer show it with the appropriate expression” (Pliny the Elder, “Natural History” translated by Irena and Tadeusz Zawadzcy). Indeed, the covered face of Agamemnon, broken by pain, has a stronger impact on the viewer’s imagination than any other attempt to convey his suffering with a brush.

Unfortunately, the provincial Pompeian fresco does not emphasize the characters’ feelings as strongly as the Greek original probably did. In this respect, the only thing that connects both works is the figure of Agamemnon – like Timantes, the Roman painter hid the face of his distraught father. It is possible that the creator of the fresco did not even see the original. It is possible that he painted it himself, inspired by another copy of it. It is possible that he only heard about the old master’s trick of covering his face. There are too many differences between the fresco from Pompeii and the description of Timantes’ painting presented in Pliny’s “Natural History” to be considered a faithful copy.

Iphigenia was sacrificed and the Achaeans won the war. As a consolation, I will add that in some versions of the myth, Artemis saved Iphigenia: in one of them, Agamemnon’s daughter ascended to heaven, in another – she continued to live on earth.

In conclusion, a small digression: it is impossible not to notice a certain parallel between the ancient Greek story about the fate of Agamemnon’s daughter and the Old Testament story about God demanding Abraham to sacrifice his son, Isaac. But the difference between the two situations is significant – in the Old Testament, Abraham trusts God implicitly and is ready to make the highest sacrifice for Him; only at the last moment, having realized the fervor of Abraham’s faith, God changes his demand and allows Isaac to be replaced on the altar by a ram. Faith and divine mercy come first here. The Greek tradition places the emphasis in a completely different place – even if Artemis saved Iphigenia at the last moment like Yahweh saved Isaac, her divine judgment is shown in mythology as quite cruel and incomprehensible whim that man cannot oppose. Instead of faith in divine goodness, the focus was placed on fatherly suffering, which has nothing to do with love for the gods. It is not faith that forces Agamemnon to sacrifice his daughter, but the tragic choice that the gods put before him. Even Iphigenia, who comes to terms with her fate, does not do it out of faith, but to fulfill her duty to her homeland and her compatriots. When you look at it from a certain perspective, you can clearly see the completely different philosophy of both traditions – one that puts the human being and his feelings first, and the other one that subordinates man to God. These are not only two different religious systems – they are even two completely different ways of thinking.

If you are curious about the story illustrated in the painting, it is worth reading the ancient tragedy entitled “Iphigenia in Aulis” by the Greek playwright Euripides. It can be found legally on the Internet as free reading. The fresco itself comes from the so-called “House of the Tragic Poet” in Pompeii, and currently hangs in the Archaeological Museum in Naples.