Chapters

The Capitoline Temple was the most important place of Roman state religion. Due to the strong connection between religion and politics, it also performed many other functions. The proof of its uniqueness is the fact that it was built in the royal era and retained the status of the largest Roman temple for several centuries. For almost a millennium, it towered over Rome from the Capitoline Hill. During this time, it was destroyed many times, but each time it was rebuilt.

Aedes Capitolina

The Capitoline Temple (Aedes Capitolina) was the temple of the Capitoline Triad. It consisted of the three most important deities of the Roman state religion, namely: Jupiter the Best, the Greatest, Juno Regina and Minerva. However, the dominant role belonged entirely to Jupiter. The temple itself was dedicated primarily to this god. This is reflected in the name, as it is also called the Temple of Jupiter the Greatest (Templum Iovis Optimi Maximi; or Aedes Iovis Optimi Maximi[Capitolini]) . The difference between the Latin terms: aedes and templum exists, but from the perspective of our culture it is imperceptible. Well, both can be translated as temple. The first term actually means a building performing religious functions, while the second one also refers to an object performing such functions, but it definitely does not have to be a building. It was a separate, marked and clearly fenced-off space dedicated to deities through the act of inauguration. The problem is further complicated by the fact that aedes were often built in the templum area. This difference, however, was described mainly in the works of Roman antiquarians. Therefore, we are not sure whether the Romans of the Imperial era distinguished between these two terms.

The First Capitoline Temple

Relatively very little is certain about the history of royal Rome, and this is also the case with the beginnings of the history of the Capitoline Temple. The main source of knowledge, apart from archeology, is the monumental work of Titus Livius Ab urbe condita. Legends contain information that the fifth king – Lucius Tarquinius the Old – supposedly vowed to build a temple to Jupiter the Greatest. It was supposed to happen during the battle. Then he was to prepare the area for the temple. Terracing was necessary due to the shape of the land on which the building was to be built. Modern research has shown the historicity of land leveling works. The murder of Lucius Tarquinius the Old had a negative impact on the intensity of work. However, invaluable progress was made by his son (or grandson), the last king of Rome – Lucius Tarquinius Superbus. He was to complete the foundation work and then build a large temple. Etruscan specialists were additionally involved in the work. The amount of work the king put in and its effects are best documented by the fact that Titus Livius, a clearly reluctant ruler, admired them:

It was he who began the war with the Volsci which was to last more than two hundred years after his time, and took Suessa Pometia from them by storm. [3] There, having sold off the booty and raised forty talents of silver,1 he conceived the project of a temple of Jupiter so magnificent that it should be worthy of the king of gods and men, the Roman empire, and the majesty of the site itself. The money from the captured city he put aside to build this temple.

– Livy, I: 53

Titus Livius further writes that after the oligarchic revolution, the new authorities in the person of the consul Marcus Horatius Pulwillus made an act of dedication (consecration) of the temple. Plutarch adds that Publius Valerius Publicolus, Horatius’s personal rival, wanted to prevent him from doing this, because he ordered him to tell him a lie that his son had died suddenly. However, the consul correctly carried out the consecration of the temple. According to Livy, this was to happen on September 13 of the year in which the regime changed; it was therefore 509 BCE according to Varronic chronology.

According to ancient historians, the act of dedication described above is shrouded in controversy. Their cause is the tradition of hammering one nail into one of the columns on each anniversary of the temple’s dedication. This gave the Romans the opportunity to know the exact year of dedication by counting these nails. We know that this was done by the aedile of 304 BCE, Gnaeus Flavius. His count showed that the temple was dedicated in 512/511 BCE, i.e. before the change of regime. So was the version transmitted by Titus Livius an accidental error? Very likely not. The Romans lied deliberately because they did not want to admit that the greatest temple in Rome was not only built but also dedicated by the last king. This is related to a strong aversion to the royal system, to the title of rex, and especially to its last bearer. The Romans wanted to take away the glory of dedicating the temple to the last, hated king, and use it to illuminate the beginnings of the history of a new, republican system, allegedly established by themselves. Defenders of tradition refer to the fact that Horatius’s name was written on the temple’s architrave. However, its opponents have a strong counter-argument. Namely, it is natural that the new regime rededicated many holy places, including the most important of them – the Capitoline Temple.

Returning to the topic of building the temple, Roman tradition mentions two positive omens that were supposed to take place. Well, according to Roman religion, auspices took place before construction. The goal was to make the area for the temple free from old obligations. In this case, it was extremely necessary, because already in the royal era, the Capitol was a place of various cults of many deities. Almost all of them agreed to leave the occupied area, giving the inaugurated place to Jupiter. The exception was supposed to be Terminus – the god of borders. The Romans interpreted his disagreement as an expression of the permanence of state borders. Moreover, Dionysius of Halicarnassus wrote that apart from Terminus, the goddess Juventas also disagreed. The second omen was the discovery while digging the foundations, of the head of a man with a very well-preserved face. With the help of Etruscan soothsayers, it was to be determined that Rome would be the head of a great empire. This is also where the designation of Rome as the head of the world (caput mundi) comes from.

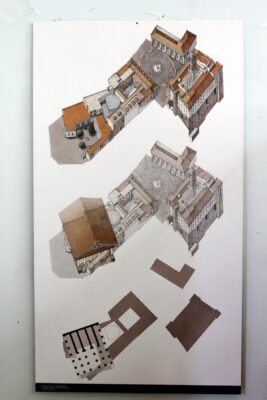

The main building material of the temple was wood, and terracotta was used for decoration. The dimensions of the building remain the subject of speculation among researchers. Two theories dominate. The first assumes a rectangle with sides of length: 55 m and 65 m; the second one is a square with a side of 60 m. It is certain, however, that it was built in the Tuscan order. It was built on a 5 m high podium. The foundation slab was made of a special type of tuff, most of which was obtained while levelling the construction site. The three sides of the temple were surrounded by a colonnade, with six columns along each side. However, there were two additional rows of columns on the front side, so there were eighteen of them in total. They formed a portico in front of the cellas. The entire building was covered with a gable roof. Each deity of the Triad had its own cella.

The middle one belonged to the most important one – Jupiter; right – to Minerva; left – to Juno. In each cell there was a cult image of a deity. There were also, but naturally less exposed, other sculptures, especially of deities closely related to the main ones, an example was the image of Summanus. The most characteristic sculpture, however, was on the roof, as it was an image of Jupiter leading a quadriga. The iconic statue of Jupiter depicted him proudly wielding lightning. He was dressed in a tunic decorated with palm leaves (tunica palmata) and a purple toga decorated with gold thread (toga picta). The authorship of both sculptures is attributed to the Etruscan artist, Vulca of Veii.

The Capitoline Temple witnessed an extremely difficult episode in the history of Rome, which, due to its consequences, stopped further Roman expansion for some time – the invasion of the Gauls in 390 BCE. After the defeat at the Battle of the Alia River, Rome was plundered. The place where the Romans defended themselves the longest was the Capitol, whose largest building was the temple. Plutarch reports that the siege of the Capitol lasted as long as seven months, and its defenders finally defended the temple against the invaders.

The first documented, broader renovation of the temple took place at the beginning of the 4th century BCE, when some elements were replaced. However, the new elements differed in style from the original ones. The next such renovation took place at the turn of the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE, the dismantled elements found a place in the Area Capitolina. In 179 BCE, the walls and columns were re-plastered. After the Third Punic War, a mosaic floor was added. Year 83 BCE brought the destruction of the temple. On July 5, it burned down during the fighting of the First Civil War.

Temple restoration

During his dictatorship, Sulla immediately took action to rebuild the temple. He brought to Rome incomplete parts of the gigantic columns of the Temple of Zeus, which he took over in 86 BCE, during the sacking of Athens. Old foundations were used to build the second temple, and it was built in the same style, but using more precious materials. New cult statues were also carved. The author of the statue of Jupiter was Apollonius of Athens. However, this time it depicted Jupiter sitting, holding a thunderbolt, a scepter and the image of the goddess Roma in his hands. The temple was finally rebuilt only at the end of the 1st century BCE, but the act of rededication was not delayed that long. In 69 BCE, this honor was granted to the consul Quintus Lutatius Catulus.

The structure survived the rest of the civil wars of the fall of the Republic. However, it came to the center of events in 44 BCE when Brutus and other Caesaricides locked themselves inside it after committing murder. The next fire caused by a lightning strike in 26 BCE did not result in major losses. Nevertheless, the temple was renovated by Augustus. The end of the second temple building brought the so-called year of the four emperors. During violent fighting in Rome between the troops supporting Vespasian and the supporters of Vitellius, on December 19, 69 CE, the temple burned down.

One of Vespasian’s priorities after taking power was the reconstruction of the Capitoline Temple. The third temple was built on old foundations, but was significantly higher. This is how Tacitus presented its reconstruction:

The charge of restoring the Capitol was given by Vespasian to Lucius Vestinus, a member of the equestrian order, but one whose influence and reputation put him on an equality with the nobility. p101 The haruspices when assembled by him directed that the ruins of the old shrine should be carried away to the marshes and that a new temple should be erected on exactly the same site as the old: the gods were unwilling to have the old plan changed. On the twenty-first of June, under a cloudless sky, the area that was dedicated to the temple was surrounded with fillets and garlands; soldiers, who had auspicious names, entered the enclosure carrying boughs of good omen; then the Vestals, accompanied by boys and girls whose fathers and mothers were living, sprinkled the area with water drawn from fountains and streams.

– Tacitus, Annals IV: 53

It was decorated with, among others, quadriga and bigas led by the personifications of victory – the goddess Victoria. The next act of dedication took place in 75 CE, and Vespasian kept this honor for himself. However, he did this not as Augustus, but as consul. However, the temple built by Vespasian did not last long, a year after his death (80 CE) it burned down again due to a lightning strike.

The third temple burned down during the reign of Titus Flavius. At that time, this ruler also had to deal with the effects of the eruption of Vesuvius and the raging epidemic. This was reflected in the fact that he did not take sufficient action to rebuild the Capitoline Temple. However, it was rebuilt by the next emperor – Domitian. The emperor rebuilt the temple on a grand scale. The old foundation was reused, and, according to tradition, the rebuilt temple was superior to its predecessor. This time, white marble was used on a large scale. This allowed temples to be protected from fires in the future. The testimony of Plutarch, according to which Domitian devoted at least twelve thousand talents of gold just to gilding roof tiles, is a testimony to this grand scale. In the central point of the pediment there was an image of Jupiter sitting on the throne, flanked by the goddesses Juno and Minerva. Under the thrones of the gods, an eagle with spread wings was depicted, and bigas were depicted on the sides of the thrones. The corners of the cornice were crowned with images of the goddess Venus and the god Mars. Domitian also did not delay the fourth (or fifth) act of dedicating the temple. He accomplished this in 82 CE, as did his father, Vespasian, as consul. The fourth Capitoline Temple was much more durable than its predecessors, surviving in good condition for the next three centuries.

Twilight of Splendor

The end of the splendor of the Capitoline Temple built by Domitian was not brought by another fire or a violent civil war. It occurred with the end of the splendor of the cult of Jupiter, or in a broader perspective, with the end of the splendor of paganism and traditional Greco-Roman culture. The Christian emperor, Theodosius, closed traditional temples, including the Capitoline Temple, as part of his persecution of pagans in 392 CE. The temple became an object of robberies. The fact that the Romans themselves did this is highly symbolic. Zosimos informs that Flavius Stilicho looted the gold decorating the temple doors. Procopius of Caesarea, in turn, reports that the temple, like many other Roman buildings, fell victim to the Vandal invasion in 455 CE. As part of the plundering of the Eternal City, Genseric was said to have torn off the gilded roof tiles. In the 6th century, the process of decline continued, the Byzantine commander Narses deprived the temple of many sculptures and other decorations in 571 CE. The temple, although robbed, survived the Middle Ages in relatively good condition. However, it was almost completely destroyed in the 16th century, when Giovanni Pietro Caffarelli built a palace in its place (Palazzo Caffarelli). As a result, for the next two centuries, even the location of the temple was forgotten. The state of affairs changed only with excavations carried out in the 19th century.

As a result of almost two thousand years of plundering and new development of the area, only fragments of the foundations have survived to this day. A rather large fragment of the foundation wall can be admired today in the Capitoline Museums. Other fragments can also be found in Piazzale Caffarelli and in Via del Tempio di Giove.

Features

To sum up, the Capitoline Temple began its period of splendor with the first dedication, which, without going into the controversy, certainly took place in the 6th century BCE. This period ended with the decline in the popularity and political importance of the cult of the Capitoline Triad, which occurred in the 4th century CE. The period of the temple’s splendor, during which it was destroyed but was rebuilt without unnecessary delay, lasted almost a millennium. During this period, she performed many different functions.

Apart from the obvious religious function related to the cult of Jupiter Best and the cult of the entire Capitoline Triad, it served another invaluable religious function; namely, it was where the Sibylline Books were kept, which, according to legend, were purchased by Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, the main builder of the temple. One can also draw a far-reaching conclusion that it also had, in a sense, a cultural function; more precisely, its history presented a certain symbolism that passed into tradition and history. Namely, its tragic periods coincided with the tragic periods of Rome. The first temple burned down during the First Civil War; the second – also during the Civil War; the third – after the eruption of Vesuvius and during the plague; the fourth – during the decline of traditional culture, being at the same time the culmination of this process. This conclusion is also expressed in a fragment of a poem by Horace, in which he writes that the fame of Rome will last as long as a pontiff and a vestal virgin enter the Capitol. Generally speaking, the Capitoline Temple also served as a state archive, one could say, a museum in the modern sense of the word. For many centuries it was possible to see, among others, the armor, shield and sword of Lars Tolumnius – the most famous king of the Etruscan city of Veii, defeated in battle by the weapons of the Roman Republic. The temple also kept many documents, such as tablets with covenants and laws.

During its heyday, the Capitoline Temple also had strictly political functions. It was she who witnessed the consuls taking the oath and taking office. This function guaranteed her constant presence in the political life of Rome. However, she was also present in extraordinary situations; namely, this was where the triumphal procession was heading, which was the greatest form of self-presentation of the power and glory of the Roman Empire. It was in the Capitoline Temple that the victorious leader made sacrifices, ending his triumph.