Roman Empire was a country extremely open to internal migration; additionally, it relocated troops (especially auxiliary troops) to areas far from their homeland. This is evidenced by the preserved, inter alia, tombstones of soldiers and people associated with the military stationed near Hadrian’s Wall.

For example, in northern England, a tombstone of a certain Wiktor was found, who was a freedman of one of the cavalry soldiers. Next to his name is the inscription “Moor”, clearly suggesting North Africa as his land of origin.

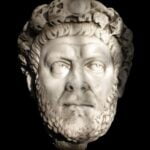

Another example of a “military” who did not come from Britain, or even Gaul or Germany, was Quintus Lolius Urbikus – the governor of Britain in 139-142 CE. – which, de facto, came from what is now Algeria; there, in the city of Tiddis, the Urbikus family tomb was found.

We also know the name of a certain Barates, who came all the way from Palmyra (Syria) and took part in the construction of Hadrian’s rampart in the 2nd century CE. From the preserved tombstone of his wife Regina, near Fort Arbeia, we can read that she came from the local Katuwelan tribe and died at the age of 30. Her name was written in Aramaic, and the initiator of the construction of the monument was Barates. This tombstone proves how exotic relationships arose in the Roman Empire and how far migrations were possible thanks to living in one large country.