Chapters

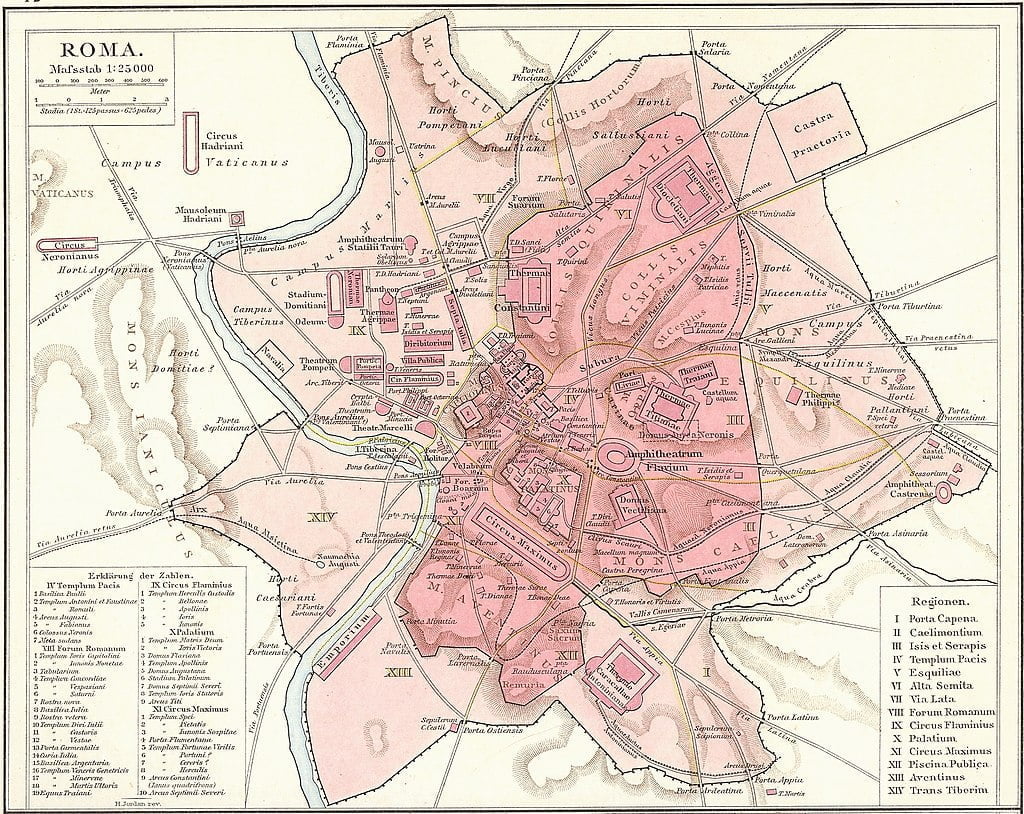

Romans left behind many buildings – amphitheatres, roads, aqueducts, temples and forums. Is that all? It turns out not; the walls, and in particular the Aurelian Wall, is an example of the pragmatism, ingenuity and genius of Roman engineers. About 19 kilometres long, with hundreds of towers, thirteen gates and over a hundred latrines – these are just a few numbers behind which there is an extremely interesting history of the city and the empire.

Good bad beginnings

Roman achievements in the field of structural engineering include roads, aqueducts, bridges and countless buildings that still arouse admiration among us today. One of the lesser-known structures is the Aurelian Wall, a structure of impressive size that kept the city safe long after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The wall was built as a response to this

far-reaching attacks by barbarian tribes.

The decision to erect the wall was made by Emperor Lucius Domitius Aurelian after defeating the Germanic Jutung tribe, which caused him a lot of trouble in the first phase of his rule.

Statistics…

The Aurelian Wall was built for ten years from 272 to 282 and was completed by Emperor Probus. The length of the wall was 19 km (exactly 18,873 m), which means that exactly 5.17 meters were built per day. This value is even more impressive when we realize that the average height of the wall is 7 m and the minimum thickness is 3.5 m. It is easy to calculate that 126.7 cubic meters of building materials were used daily! The building material, in turn, was not rocks or bricks, as we might have guessed, but concrete. In addition, we must realize that the construction was not only about pouring concrete but also about preparing the ground for this building, making square towers every 100 Roman feet (or 29.6 m), additionally creating many arrowslits, placing 13 gates and 116 latrines (on average one per 164 meters) and countless chambers and warehouses. The Romans decided not only on practice but also on aesthetics, where the uninteresting façade of the wall was covered with brick.

… and numerous tricks

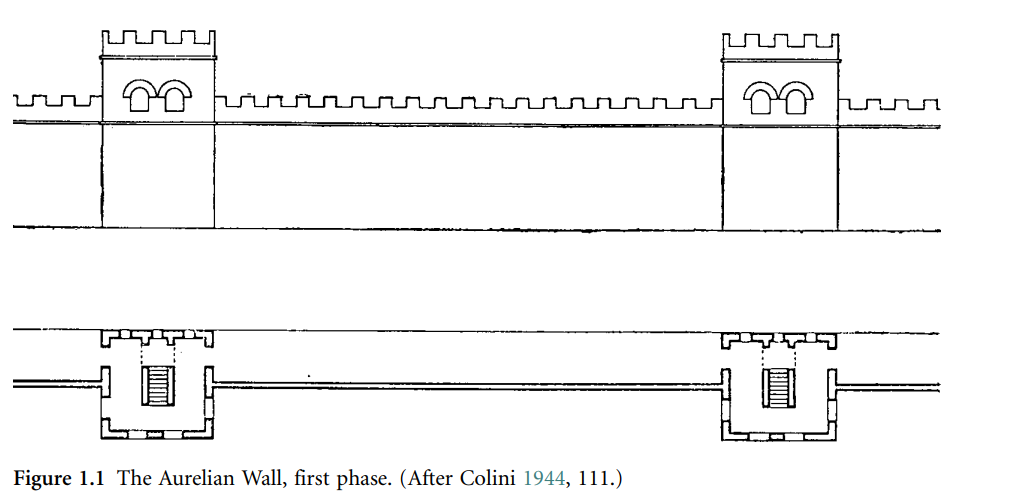

It is certain that for the most part, the wall had a solid concrete core, but at the top of the wall, you can find many different solutions for walkways and arched galleries. Basically, the scheme of the wall can be presented in the figure below.

In order to construct such a colossal structure in such a short time, many tricks and solutions were used to use the existing infrastructure. For example, in the vicinity of the Ponta Maggiore and Ponta Tiburtina gates, the wall is built just behind the arches of the aqueducts, to which the wall was added by filling the empty spaces between the arches of the aqueduct structure. As a result of this procedure, the wall in this place is up to six meters thick.

Savings – or Roman pragmatics

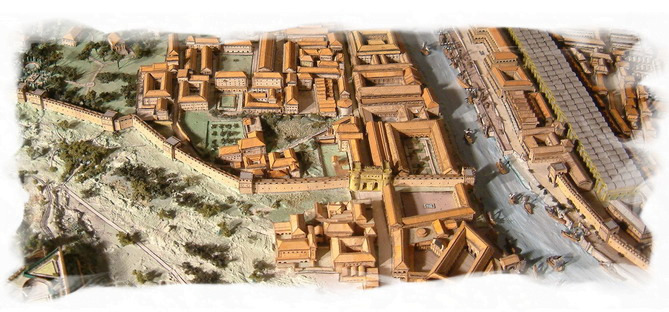

Moreover, the practical nation of the Romans did not put up a wall according to the above scheme. Where the threat was less or the terrain more difficult, the Romans made fewer towers and the wall had a lower height. We are talking here, especially about the areas on the Tiber, often flooded and difficult to conquer, even without walls. In the model below you can see the course of the wall by the Tiber River.

The wall as a defensive structure

Securing such a huge city as Rome in the 3rd century CE requires not only erecting a high wall but also organizing places of active defence. This task was fulfilled by towers on a square plan, which, as mentioned earlier, were located every 100 Roman feet. These towers were 7.5 to 7.75 m wide and protruded 3.5 to 3.75 m from the face of the wall, which means that the towers were embedded in the wall. The structure of the towers was also made of concrete. The thickness of the walls was two Roman feet (about 60 cm). Each of the towers had five windows, two at the front and on the sides, and one at the back. The windows allowed the use of defensive machines, including ballistae. Interestingly, the number and location of windows and curtains (narrow openings in the wall for archers) differ, which is the result of work carried out by several dozen working groups, which may have had limited contact with each other.

Pira-mur? The only combination of wall and pyramid in the world!

Roman pragmatics? Well, it wasn’t always like that. In Augustinian times, Rome was swept by a wave of Egyptomania related to the conquest of Egypt by Octavian Augustus, who considered himself a descendant of the Egyptian pharaohs. This started a new fascination with ancient Egypt. Obelisks and Egyptian-style architecture and sculpture were installed in the Roman forums. The cult of Isis, the Egyptian mother goddess, had a huge impact on the entire empire. One of the most impressive buildings is the pyramid of Cestius, a tomb located at via Ostiensis, leading to the port of Ostia. This building was erected around 12 BCE for Gaius Cestius, praetor, tribune of the people and member of the college of epulones, i.e. the college responsible for organizing cultural events in the city. After the fall of Rome, for a long time, it was believed that the pyramid was the resting place of the mythical Remus. The building has been immortalized many times in drawings and sketches. An interesting picture of the state of the monument in the 19th century is the watercolour by Wiktor Nicolle presented below.

[picture_frame img=”106259″ alt=”Cestius’ pyramid” imgw=”600″ float=”center”]Cestius’ pyramid[/ramka_ze_zdjeciem]

As it turns out, the tomb more than two hundred years later became a problem because it stood in the way of the wall. Instead of demolishing the existing monument, it was decided to add a wall to it.

Gates to Rome

In the beginning, the Aurelian Wall had thirteen gates; then five more were added. The four largest and most important are Portae Flaminia, Appia, Ostiensis and Portuensis, all of which almost certainly had two arches of travertine (a porous sedimentary rock composed mainly of calcite and aragonite, called Egyptian alabaster), one each for incoming and outgoing traffic, surrounded semi-circular brick towers. These gates underwent constant changes and reconstruction. Currently, the facades bear little resemblance to Aurelian’s times and are the result of many beautifying treatments; however, there is still ancient concrete under a thick layer of ornamental stone. Below is a picture showing the area around the wall with Porta Portuensis.

What’s next for the wall?

Today, more than two-thirds of the walls are still where they were placed nearly two thousand years ago, reminding us of the genius of Roman engineers.