Probably each of us has heard of Pontius Pilate, the most famous Roman prefect of Judea and one of the most famous in the entire history of ancient Rome. However, outside the NT, few people know that there are other sources about this character.

Overall, however, little is known about Pilate. The sources for him are the four New Testament Gospels, the Message to Gaiusby Philo the Jew of Alexandria, and The Jewish War and The Old History of Israel by Josephus. Other sources include the Annals of Cornelius Tacitus and the Ecclesiastical HistoryEusebius of Caesarea, a church historian. Pontius Pilate is also mentioned in some other writings, the so-called Apocrypha1.

Was Pilate really a good steward of Judea? Let’s look at some situations during his reign. The first of them will be the scandal described in The Jewish War that the prefect caused. The reason for the scandal was the bringing to Jerusalem by a cohort of legionnaires of the so-called imagines(images of the emperor). Josephus believes that it was done with pure premeditation, while Dr Adrian Goldsworthy, a researcher of ancient Rome, believes that it was not a provocation on the part of the prefect, but rather an ignorance of social moods; he probably thought that the Jews would accept it as a mere insignia of power and that only the fiercest opponents of Rome – the Zealots2 would eventually raise some voices of discontent, which would quickly die down. The fact that it was not a provocation is also evidenced by the fact that imagines were introduced into the city at night, and not ostentatiously during the day. The researcher also points out that after the legation from Jerusalem showed with their attitude how much these banners offended the Jews, Pilate ordered them to be removed3.

On another occasion, Pilate used money belonging to the Jerusalem Temple to build an aqueduct, bringing clean water to the city; instead of gratitude, he met with protests[note id=”4″].

Yet another example is the setting of golden shields in Herod’s palace. Researchers do not know exactly why they offended Jews. They probably contained some inscription about the divinity of the emperor, although no source states exactly why these shields caused such outrage. Only after the sons of King Herod wrote a complaint to the emperor, did he rebuke Pilate and order the shields to be removed.

Dr Adrian Goldsworthy argues that the accounts of Pilate are exaggerated, pointing out that his greatest critics, Philo of Alexandria and Josephus, can point to only a few incidents that are not as clear-cut as the above Jewish authors portray.

The incident with imagines, which were brought in at night, can be interpreted as Pilate’s deliberate action to spite the Jews under the cover of night and bring them to a fait accompli, or as a desire to pay respect to the emperor while avoiding misunderstandings and brawls from the followers of the Jewish religion. No one knows why the golden shields offended the Jews, and the construction of the aqueduct with the money from the Temple of Jerusalem was dictated by the need for the city to be better supplied with clean water. After all, no source unfavourable to the prefect mentions that Pilate built the road to the Temple of Jerusalem, discovered in 2019, to make it easier for pilgrims to get there5.

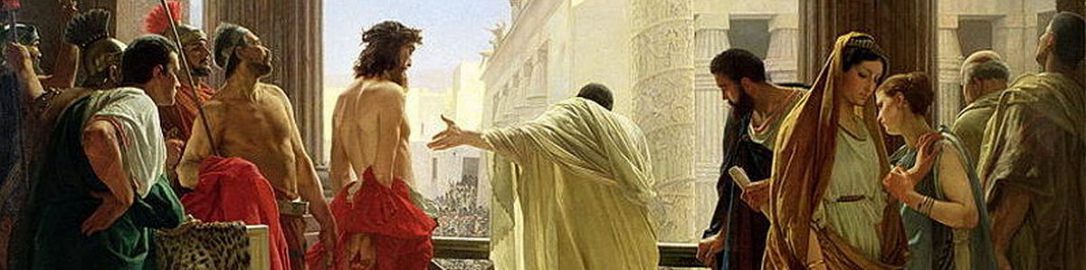

Pilate, like any other representative of Roman power in Judea, had no easy task. He was pragmatic and had to reckon with the fact that the Jews never got over the loss of their sovereignty and looked hostile to anyone who helped the Romans6. He could not be too compliant or too brutal, especially during Passover, when Jews from all over the world flocked to Jerusalem, and every decision was connected with the spectre of a clash with a discontented crowd. Dr Goldsworthy concludes that Pilate was a good prefect, he did not seek unnecessary conflict, relented when the situation called for it, and used violence when necessary. He had to skilfully manoeuvre between Rome and Judea, maintaining a balance between the rule of a firm hand and certain concessions.