Chapters

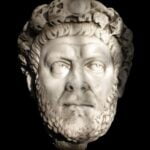

The life of Constantine the Great was not an easy one. He had to face more and more new problems, and the higher he climbed in his political career, the more of them there were. The emperor had an ambitious and clever woman at his side – Fausta. One time she saved his life by defending him from his own father. However, this made Constantine decide to get rid of her.

Background

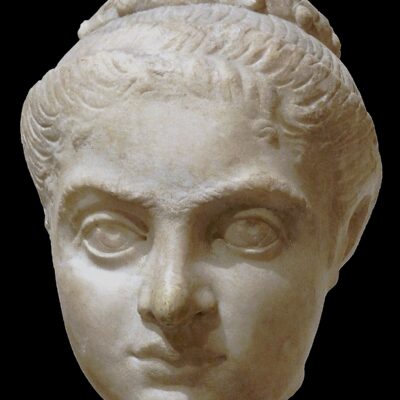

Fausta was the daughter of Emperor Maximian and his second wife Eutropia. Her older sister Theodora became the wife of Caesar Constantius I Chlorus, who, as Caesar, was subordinate to her father in the tetrarchy system then in force in the empire. Fausta also had an older brother – Maxentius.

Maximian co-ruled with Diocletian from 286. According to previous arrangements, both were to abdicate in 305, leaving the throne to their successors: Caesars Constantius and Galerius. Maximian, however, was not willing to give up the purple. He tried to persuade Diocletian to continue to wield power, but these attempts were unsuccessful. Maximian had to abdicate on May 1, 305 in Milan and then went to his estate in Lucania. However, this was only the beginning of the problems.

Constantius Chlorus died in Britain in 306 and, contrary to the applicable rules, the army proclaimed his son, Constantine, emperor. He was about 26 years old at the time and was in a relationship with Minervina, with whom he had a son, Crispus (born around 303). The young emperor tried to quickly legalize his power in Britain and Gaul and deal with the Frankish invasion on the Rhine. Also in 306, Maxentius usurped power in Italy and invited his father, Maximian, to co-rule. Chaos broke out in the empire. Galerius, the emperor of the East, had no intention of recognizing the usurpation and attacked Italy. He had previously recognized Caesar Constantine’s authority in Gaul and Britain. Fausta’s father and brother found themselves in a very difficult position. Maxentius set out to face Galerius, and old Maximian was about to ally with Constantine. At this point, Fausta appeared on the political scene.

Marriage

Maximian traveled to Trier to ally with Constantine, or at least to ensure his neutrality. The negotiations were very long due to the indecision of the young Caesar, but in the end it was agreed that Constantine would receive the title of Augustus (which gave him the highest, equal power with Galerius, Maximian and Maxentius) and the hand of Fausta. The wedding most likely took place on Christmas Day 307. For it to take place, Constantine had previously separated Minervina from him (this is strikingly similar to the action of his father towards Constantine’s mother – Saint Helena). Moreover, there are signs that the marriage of Constantine and Fausta was planned in 293 by Maximian and Constantius, but these plans were abandoned. In 307, Fausta became empress alongside Constantine, later called the Great.

Family disputes

Serious disputes quickly arose in the family system that ruled the western part of the empire (Maximian and Maxentius in Italy, Constantine in Gaul and Britain). Within a few months, Fausta’s father quarreled with his son and in 308 he attempted to overthrow him, which he failed. He fled from Rome across the Alps to his daughter and son-in-law. He received him with dignity, but had no intention of giving him any help.

The situation in the empire was tense: six emperors ruled at the same time. The meeting of the most important of them in 308, to which Diocletian himself was invited, did not solve anything. Maksymian had to give up the purple again and leave. However, the ambitious old man did not give up.

In 309, Constantine set out across the Rhine to launch a campaign against the Franks, leaving Fausta in Gaul. Her father quickly arrived there, waited for his son-in-law to cross the river with his army, and proclaimed himself emperor in his place, declaring Constantine dead. He also started handing out money to soldiers, who, however, were not fully convinced that the young emperor was dead. When Constantine learned about the whole situation, he immediately turned south, interrupting the campaign and trying to storm the city of Massilia, where Maximian was defending. The urban population betrayed the old man and opened the gates to Constantine. The son-in-law humiliated his father-in-law by tearing off his purple coat, but spared his life.

According to Lactantius’ account in the work De mortibus persecutorum, another drama took place immediately afterwards. Humiliated, old Maximian intended to take revenge on his son-in-law and seek power again. In 310, he wanted to persuade Fausta to cooperate in the assassination of her husband. She promised to help her father and leave the bedroom door open for him, but immediately warned Constantine. When Maximian burst into the bedroom and intended to kill his sleeping son-in-law, it turned out that one of the eunuchs was lying in his place. Fausta’s father was caught red-handed and then hanged on her husband’s orders (or committed suicide himself).

At the height of power

In 312, Constantine defeated Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge and took power in the Eternal City. War between Fausta’s husband and her brother was inevitable. However, Fausta always supported her husband – both in the dispute with her father and in the war with her brother. From 312, Constantine worked very hard to bring the political and religious situation in the empire under control. In 313, he issued the famous Edict of Milan together with Licinius, and then tried to resolve the dispute between Catholics and Donatists. He was tired and upset with the lack of results and stayed in Gaul for a while with Fausta. Their first son, Constantine II, was born in Arelate in 316. In the following years, Fausta gave birth to Constantius II, Constantina and Constantine. The names of the children clearly indicate the empress’s intentions to ensure the succession of her descendants. This, as we will see, will take her to her grave.

Fausta enjoyed a very strong position at court, and the pinnacle of her career was when she was awarded the title of Augusta in 323. Despite her enormous influence and undisputed place at her husband’s side, she was not liked by his mother, Helena. Moreover, it was Constantine’s firstborn son with Minervina who was considered his main successor. Crispus was about twenty years old in 323 and was the favorite of his father, the army, and the people. He held the title of Caesar and, from 318, commanded several successful expeditions against the Franks and Alamanni. During his father’s civil war with Licinius, Crispus won a great victory in a sea battle in 324. He was a capable and famous commander, had wide support, and already had a wife and a son. In Crispus, Constantine saw the future of the empire first. Jealous of her children, Fausta intended to change that.

Tragic end

Fausta’s enormous ambitions led to tragedy in the imperial family. After the end of the Council of Nicaea in 325, Constantine intended to return to Rome. Suddenly, in the spring of 326, Crispus was murdered in present-day Pula in Istria on the orders of his father. The hot-tempered Constantine ordered his son’s death after he believed Fausta when she accused Crispus of trying to seduce her. The Empress took advantage of her husband’s trust and his vehemence. However, the intrigue soon turned against her.

Constantine’s mother, Helena, could not come to terms with her grandson’s death and exposed Fausta’s plot. In the summer of 326, she convinced her son that Crispus was innocent. Constantine became very angry. He ordered his wife to be locked in a hot bath, where Fausta suffocated. She ended her life on the orders of her husband who hated her. The year 326 became the darkest page in the life of Constantine the Great, who first killed his son and then his wife. He also sentenced her to damnatio memoriae.

Legacy

Fausta’s intrigue, however, achieved the effect – although certainly not the one the empress expected. Her sons became the successors of Constantine the Great. In 337, Rome was divided between Constantine II, Constantius II, and Constans. None of them left a male heir, and the last one – Emperor Constantius II – died in 361, leaving the purple to his cousin – Julian the Apostate, son of Julius Constantius, who was the half-brother of Constantine the Great.