Hadrian’s Wall (Vallum Hadriani), also called the Roman Wall or Picts’ Wall, was built in the following years 121 – 129 CE by Hadrian Emperor. It was a symbolic northern border of the Roman Empire in Britain. The fortifications ran from Bowness on Solvay Bay to Wallsend on the Tyne River for about 70 Roman miles or about 118 km. The rampart crossed the island from sea to sea.

The idea that the wall was a defensive structure and was supposed to stop barbarians from invading is nowadays strongly questioned by scientists. It is assumed that the wall marked the border and was a symbolic rather than a defensive barrier – it was certainly difficult to prevent the dykes from being crossed on such a length.

The height of the wall was about 4.5 metres in most sections. It crossed the peninsula in a very narrow place and protected against attacks of mountain tribes from the area of today’s Scotland. Contrary to its name, it was not an earth rampart. The eastern part of the wall was built of stone and brick, and the western part of the wall was built of turf.

Every 500 meters there are watchtowers and every 1,5 kilometres there are small forts. In the background there were roads, and in the foreground there were moats. 750, 000 m3 of stones were used to build the monument.

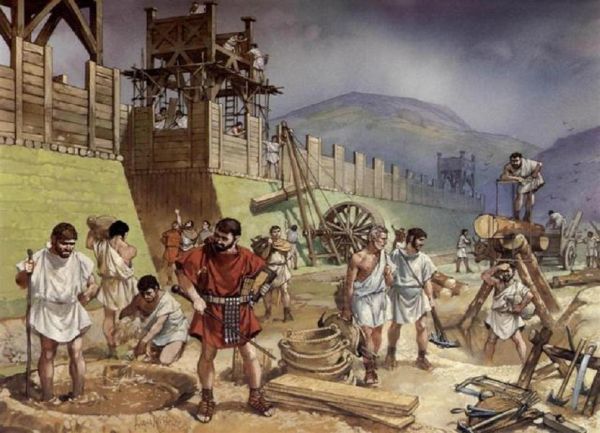

This impressive work of military engineering was built in just a few years. The main builders were legionaries (3 legions) and auxiliary units stationed there, as the army was used to work at the borders. The Hadrian border became home to 10, 000 soldiers.

The main purpose of the Hadrian Wall was different from the traditional city walls. Hadrian’s embankment was not just a barrier to the pressure of the northern tribes but also had an important political function. It prevented warring Brigands from coming into contact with the Caledonian tribes, mainly Selgogies, by controlling access to the border zone.

The Hadrian’s rampart consisted of 6 elements: a wall with a ditch from the front; mileage watchtowers (bourgeois) placed every 1 Roman mile; watchtowers – 2 for each mile; castelli, or stronghold camps for auxiliary units; vallum, i.e. a double embankment divided by a free space and a deep ditch; a military road beyond the Wall.

Running parallel to Stangate Line (in the mid-eighties of the first century CE the construction of the defence and communication system began, located on the border of today’s England and Scotland) flat-bottomed ditch, several meters deep, was crossed by dykes connecting the forts of the Stanegate Line back-up facilities with the forehead of the fortifications of the Hadrian’s Wall. The ditch was adjacent to the ditch from the north, several metres high and at least 2. 5 metres wide stone wall (this applies to the eastern and central sector of the defence line in question), or a peat-stone embankment in its western sector.

Mileage watchtowers (bourgeoisie) could accommodate 30-50 people in the barracks, while watchtowers fulfilled observation and signalling functions, although they could also provide shelter for patrol forces.

The military route was probably not part of the original scheme, but a later addition (the earliest milestone dates back to 213 CE). It ran through the northern embankment vallum which proves that this element ceased to perform its previous functions. Construction works were carried out by legions and to a small extent by fleet units. Originally, the 76-mile embankment consisted of a 45-mile (approx. 66 km) eastern stone sector, 3 m wide and 6. 1 m high, and a 31-mile (approx. 46 km) section of wood and land, 4. 5 m wide and 3. 6 m high. It was not until later that 4 miles (about 5. 9 km) of the so-called “narrow rampart” were built in the east. (2, 4 m wide by 3, 6 m high), running up to Segedunum (Wallsend). At that time, a 5-mile (7. 4 km) section of the timber and land dyke was replaced by a “narrow dyke” to the west of Irthing. In the west, where the Wall of Hadrian crossed the territory of the Brigades, 4 of them were protruded beyond it castella: Blatobulgium (Birrens), Castra Exploratorum (Netherby), Banna (Bawcastle) and Broomholm – as control posts over that part of the Brigades’ territory which remained outside the Roman province.

The Hadrian’s Wall was complemented by the coastal defence system on both flanks. From the western end of the Embankment at the “Maia” (Bowness-on-Solway) to St. Bees Head, a system of mileage bourgeoisie and watchdogs stretched over an area of almost 40 miles (approx. 60 km), reinforced by 4 castella: Bibra (Backfood), Alauna (Maryport), Gabrosentum (Burrow Walls) and Tunnocelum (Moresby) built around 128 CE. At the same time, or slightly later, the rest of the timber-earth rampart was replaced by a stone wall (the so-called “average rampart”, 2. 8 metres thick). The east coast defence system turned from Segedunum (Wallsend) towards the Tyne River and along its southern shore to Arabei (South Shields), where stationed ala driving and fleet department.

The original defence system of the Wall consisted of 12 camps, including the bridgehead one castellum in Pons Aelius (Newcastle) for 500 people. After extending Wall to Segedunumand complementing its centre with 4 camps – Aesica, Brocolitia, Magnis, Uxellodunum– their number increased to 17; in total, the garrison consisted of about 9500 people.

The units of this garrison came from northern Britain and Wales, from where some of the camps were evacuated. Unless the crews of the mileage bourgeoisie (30 people on average) were separated from the crew castellum but from other troops, the total number of troops on Hadrian’s Embankment should be increased by about 2400 people.

The wall of Hadrian became a model for similar buildings erected by the Romans in other parts of the empire, such as on the Rhine in Upper Germany or north of the River Aluta near the Carpathians. In North Africa, at the beginning of the third century CE, a thousand kilometres long was created limes Tripolitanus, it was perfect protection of Roman estates against desert tribes.

Hadrian’s wall lost its meaning and began to fall into disrepair when Hadrian’s successor, Antoninus Pius, built new fortifications north of it, called Wall of Antoninus. However, later the Romans pushed out of the Antoninus’ rampart returned to Hadrian’s rampart, which they renewed. Finally, the wall of Antoninus conceived as a dam against the warring tribes Picts from Caledonia, he never fulfilled his hopes.