Chapters

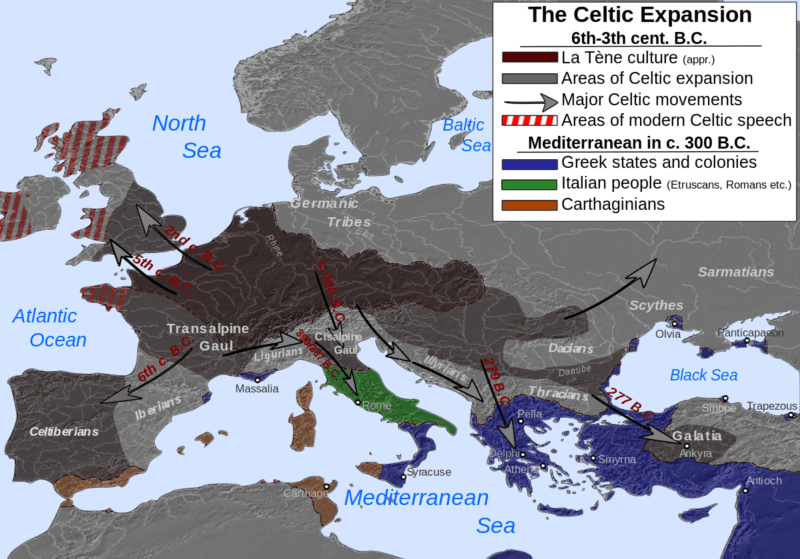

The battle of the river Allia fought in 390 BCE (according to the Roman calendar) or 387/6 BCE (according to the Greek calendar), between the Romans and Senones (one of the Gallic tribes), ended in the humiliating defeat of the Roman army. Consequently, a few days after the battle, the Gauls occupied Rome, which they plundered completely.

Background of the conflict

The Senones were one of the many Gallic tribes that invaded northern Italy. Then they settled on the Adriatic coast, around the city of Ariminum (now Rimini). According to Livy, they were called to the Etruscan city of Clusium (now Chiusi) by Arruns, who wanted to take revenge on Lucom for having seduced his wife. However, Lucom was very influential and Arruns knew that he would need outside help to take revenge. Gallic tribes were to be the tool of his revenge. When the Senones appeared, the inhabitants of Clusium fell pale in fear and asked Rome for help. The Romans sent three ambassadors, who were the sons of Marcus Fabius Ambustus, who was one of the most influential Roman aristocrats. The three brothers warned the Gauls that the attack on Clusium would lead to war because Rome would defend the Etruscans. In this situation, peace negotiations began. The Senones were ready to make peace, provided that the inhabitants of Kluzjum offer their land. During the negotiations, however, fights broke out, to which Roman MPs joined, and one of them even killed a Gallic chief. This was a violation of applicable laws, as ambassadors should be neutral. The Gauls suffered a defeat and trumpeted the retreat to consider a further action plan. Some of them wanted to march to Rome at once, but the tribal elders said it would be best to send MPs to the Romans and demand that the chief killers be handed over to them. When the deputies presented their case to the Senate, he on the one hand agreed with them and decided that the Fabius brothers, as ambassadors, should not participate in any fighting, but at the same time, he did not want to expose himself to the Fabius family, which had great influence in Rome. The Senators, not wanting to take responsibility, referred the matter to the national assembly for consideration, which in turn not only failed to accuse the Gauls (because they also preferred not to endanger the influential family), but additionally chose three Fabius brothers as new military tribunes. Enraged by such behaviour, the Gauls left Rome, threatening to open war. When the tribal elders learned that not only were the murderers not handed over to them, but they were also honoured, among the Gauls:

In the mean while the Gauls, on hearing that honour was even conferred on the violators of human law, and that their embassy was slighted, inflamed with resentment, over which that nation has no control, immediately snatched up their standards, and enter on their march with the utmost expedition. When the cities, alarmed at the tumult occasioned by them as they passed precipitately along, began to run to arms, and the peasants took to flight, they indicated by a loud shout that they were proceeding to Rome

– Titus Livy, Ab urbe condita, V.37

In view of the failure of peace talks with Rome, the Senones decided to move to Rome. The chief commander of the war expedition was Brennus.

A slightly different story describes Dionysius of Halicarnassus. According to him, Lukom was the king of the city and before his death, he gave Arruns the protection of his son. When he grew up, he fell in love with Arruns’s wife and seduced her. The betrayed husband went to Gaul to sell olives, wine and figs. The Gauls, delighted with these goods, were to ask Aruns where such goods could be found. He said to them that in a very fertile land, which is large and very sparsely populated, its inhabitants are poor warriors. He also advised them to invade this place, expel the current inhabitants and settle there themselves, which the Gauls did. The Romans sent ambassadors, and one of them, Quintus Fabius, was to kill one of the Gallic chiefs. The Gauls sent envoys to Rome and demanded that the assassin and his brothers be handed over so that they could carry out vengeance. The Roman Senate refused these demands because he did not want to expose himself to the influential and rich Fabius family. On the other hand, the senators admitted that the ambassadors were at fault and had no right to meddle in any fights. So they offered Gallom financial compensation in exchange for the death of the chief. Gallic diplomats were enraged by this and left Rome, declaring that this was reason enough for war. Chief Seon Brennus, to whom MPs reported the talks, felt humiliated by the Senate’s proposal and decided to start a war with Rome.

Battle of the Alia river

According to Livy, the Romans completely ignored the threat from Senones. Even more than usual conscripts were carried out. So they were very surprised when they learned that the Galls were within the “eleventh milestone” (i.e. sixteen kilometres). The tribunes, terrified of no laughing matter, gathered the army in haste and marched against the aggressors. Livy claims that when preparing for the battle, the tribunes made shameful mistakes. They misplaced the army, did not build fortifications or fortified the camp and, worst of all, they did not sacrifice to the gods and did not consult the soothsayers:

There the military tribunes, without having previously selected a place for their camp, without having previously raised a rampart to which they might have a retreat, unmindful of their duty to the gods, to say nothing of that to man, without taking auspices or offering sacrifices, draw up their line, which was extended towards the flanks, lest they should be surrounded by the great numbers of the enemy. Still their front could not be made equal to that of the enemy, though by thinning their line they rendered their centre weak and scarcely connected.

– Titus Livy, Ab urbe condita, V.38

Thus, the centre of the Roman grouping was Roman troops, while the wings were occupied by allied troops. Seon chief Brennus decided that the centre of Roman formation would tie his warriors in combat, while the wings at the same time would bypass his army and hit the rear. To avoid this situation, Brennus first attacked the flanks of Roman chic. It turned out to be an effective manoeuvre because the very sound of battle caused the Romans to panic and rush to flee. The sight of escaping main forces meant that allied troops also decided to desert. The Gauls chased after killing their enemies without mercy. However, the Alia River, which is a left-bank tributary of the Tiber, stood in the way of the refugees. Many of them attempted to cross the river and died in the depths of the armour due to the weight of the armour and fatigue caused by escaping. Despite the defeat, however, a large part of the Roman forces managed to escape without major losses and reach the lands of Wejhes, from where they did not send messengers to Rome, with information about their situation. The rest of the Roman forces reached the city, where the news of the defeat caused terror among the inhabitants. The Gauls themselves were surprised by their easy victory and at first, they did not move, fearing that the sudden escape of the enemy was only a strategic trick.

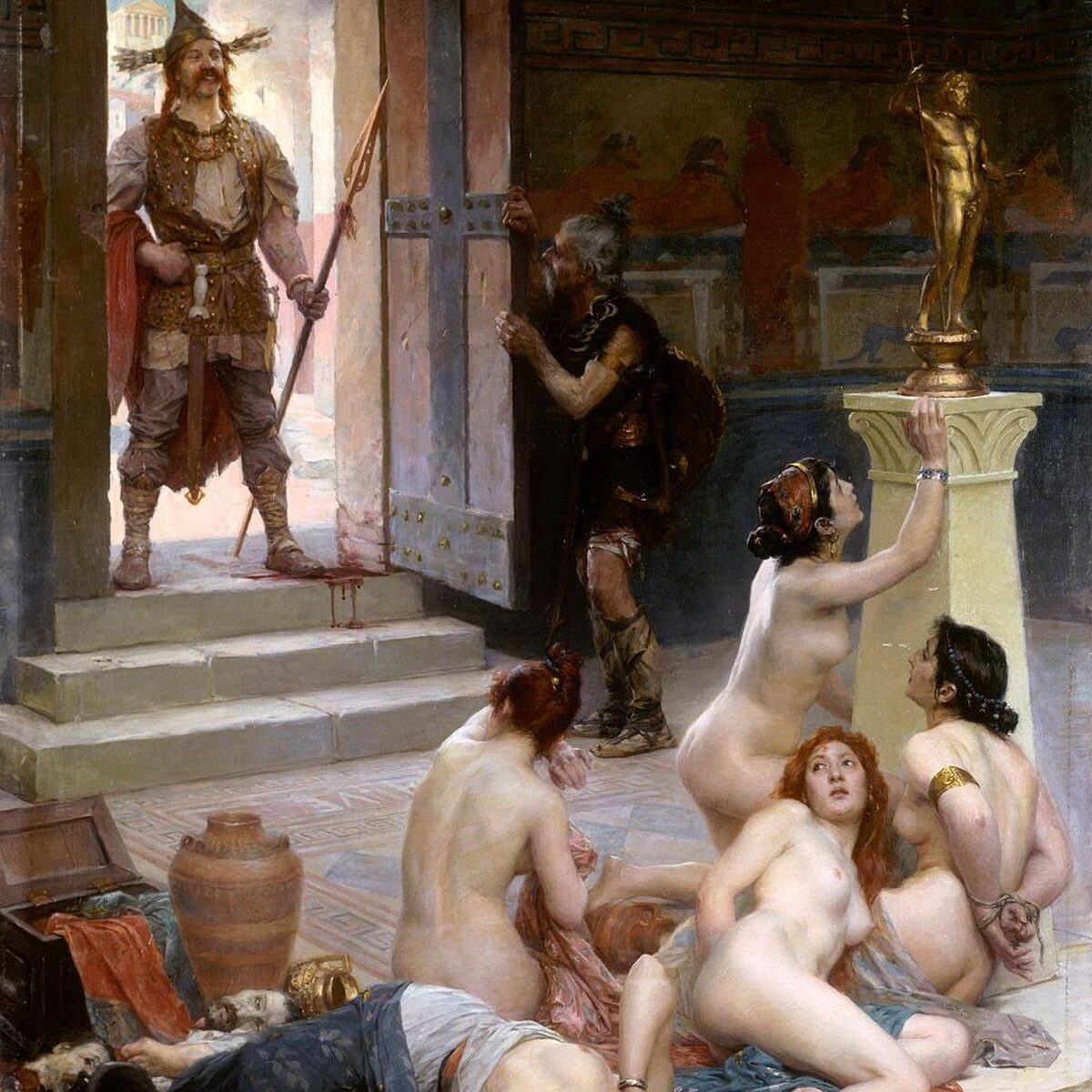

Capture and plunder of Rome

Livy described that at first, the Gauls were very surprised by their easy victory over the Roman army. For some time they did not leave the battlefield, fearing that the enemy had ambushed them somewhere. The victorious warriors devoted this time to plundering fallen enemies. Finally seeing that the enemy was not coming, they decided to continue their march on Rome. They reached the city just before sunset and here they were surprised by another view because they found wide-open gates and vacant walls. The Gauls decided to avoid a night battle in an unknown place and camped between Rome and the River Anio, postponing the morning entry into the city. Meanwhile, the inhabitants of Rome were not aware that most of their forces managed to escape to the lands of Wejhes after losing the battle. They were convinced that only the survivors who had reached the city survived the defeat. Everyone was terrified. The Romans, aware of their vulnerability, decided that the survivors of the battle, young people capable of carrying weapons, as well as young senators and their families, would take refuge on Capitoline Hill, which was turned into a defensive point. The Flamines, priests and Vestals were to take “state holiness” as far as possible from the city and ensure that the worship of the gods continued. The situation was so tragic that many old people who formerly held important state offices decided to stay in the city. Many of them followed their sons to the Capitol, but most decided to stay in their homes. Almost the entire population, for which there was no place on the Capitoline Hill, left Rome and went to Janikulum, and then dispersed into neighbouring villages and cities. Priests and vestals could take only some of the “state saints”. They buried the rest in the chapel near the house of priest Quirinus, and then left the city, along with the refugees. Then a plebeian, Lucius Albinius, spotted them, who was taking his family out of the city in a cart. He decided that it was not proper for vestals to walk, carrying precious relics. So he ordered his family to get off the cart and placed priestesses and the saints they carried, and took them to Cera, the Etruscan city that was Rome’s ally.

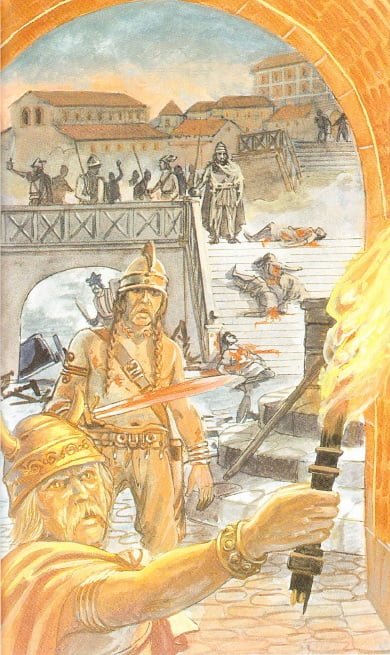

Old men who were too weak to run away decided to stay in the city and wait for their fate with dignity. Those of them who previously held high state offices waited for the Gauls in their homes, dressed in the best robes, with signs of their offices and dignity. The next day, as the sun rose, the Gauls entered the city. They passed the open gates and entered the Roman Forum. The warriors left a small squad to keep an eye on the Capitol crew, and the rest of them scattered around the city, looking for loot. Everywhere, however, empty streets and empty houses greeted them. The only ones they met were the elderly, sitting quietly in their homes. At first, the Galls were surprised and amazed at their calmness. However, this changed quickly:

Afterwards being terrified by the very solitude, lest any stratagem of the enemy should surprise them whilst being dispersed, they returned in bodies into the forum and the parts adjoining to the forum, where the houses of the commons being shut, and the halls of the leading men lying open, almost greater backwardness was felt to attack the open than the shut houses; so completely did they behold with a sort of veneration men sitting in the porches of the palaces, who besides their ornaments and apparel more august than human, bore a striking resemblance to gods, in the majesty which their looks and the gravity of their countenance displayed. Whilst they stood gazing on these as on statues, it is said that Marcus Papirius, one of them, roused the anger of a Gaul by striking him on the head with his ivory, while he was stroking his beard, which was then universally worn long; and that the commencement of the bloodshed began with him, that the rest were slain in their seats. After the slaughter of the nobles, no person whatever was spared; the houses were plundered, and when emptied were set on fire.

– Titus Livy, Ab urbe condita, V.41

Livy, however, argued that the fires were not too great, since probably Galom was more about intimidating the Capitol crew than the actual destruction of Rome. However, this had the opposite effect, because the view of burning and collapsing houses and the sounds of murder, further mobilized the defenders to fight. A few days later, when the Gauls realized that by destroying the city alone they could not break the spirit of the defenders, they decided to launch an attack on the Capitol. However, they were repelled and suffered considerable losses. This experience effectively discouraged them from further attempts to conquer the hill by storm. From that moment, the Gauls divided their forces into two parts. The first was to besiege the Capitol, and the second to plunder the nearest neighbourhood to obtain food for the army. Refugees, as well as the crew of the Capitol, in advance, stripped the city of food, and what they could not take, was destroyed by the Gauls themselves when they started the fires. Some of the Gauls reached Ardea, where an ex-Roman military leader, Marcus Furius Camillus, who was accused of embezzlement, was in exile. Camillus mobilized the inhabitants of Ardea to fight and completely destroyed the Gaul forces in the night attack. The few who survived the fight fled to Ancjum, where they were surrounded and completely killed by the local people.

Meanwhile, relative peace reigned in Rome. The Senones led a “dead” siege and only made sure that none of the defenders of the Capitol tried to sneak between their outposts. There was also an unusual incident. One of the Romans, Gajus Fabius Dorsuo, dressed in a solemn robe, left the fortified Capitoline Hill and went to Quirinale, where he made a traditional annual sacrifice, and then returned un detained to his own. Why didn’t the Senones do anything to him? Livy decided that they were either surprised by the courage and boldness of the young man or very moved by the religiosity of the Roman who, despite the tragic situation, wanted to worship his gods:

(…) Gauls being either astounded at such an extraordinary manifestation of boldness, or moved even by religious considerations, of which the nation is by no means regardless.

– Titus Livy, Ab urbe condita, V.46

Meanwhile, the soldiers who fled to the territories of Veii regrouped and chose the centurion Quintus Cedicius as their leader. They even managed to smash the Etruscan troops, which, using the confusion, tried to invade Veii’s land. From day to day, Cedicius’ strength grew, he was joined by refugees from Rome, as well as volunteers from Latium. The Centurion decided to summon Camillus and give him command, but the Senate had to agree to this because the former commander was still officially in exile. The brave Roman soldier, Poncjus Kominiius, undertook the mission of getting besieged the Capitol and obtaining permission from the Senate to dismiss Camillus from exile. He managed to sneak through the Gall posts and get to the besieged hill, where he presented the senators with the whole matter. The Senate unanimously released Camillus from exile and gave him the position of dictator, thanks to which he was able to lead the Roman army.

Meanwhile, the Senones again attempted to storm the Capitol. Probably because they discovered a not-so-steep ascent to the hill that Pontius had previously used. Under the cover of the night, they made an attempt to climb the mountain and almost managed to get behind the fortifications of the enemy. Their climb frightened the holy geese of Juno, who immediately began to make noise and woke one of the Roman soldiers, Marcus Manlius. He raised an alarm and thanks to his courage and vigilance, the Gaul attack was repelled. With this “brave” feat, the geese also saved themselves, because the hunger among the Romans caused many of them were already looking at birds with a covetous looks. The incident with the Gauls, however, caused the geese to be highly respected, and thus avoided conversion to food for the defenders.

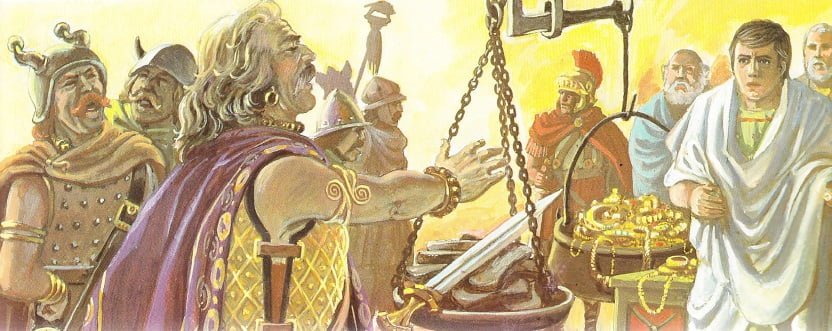

Over time, however, hunger began to oppress both besieged and besieged. Seon was additionally plagued by the plague. For their camp they chose a low place, lying between the hills, where there was malaria, so many of them died of diseases and heat. In addition, they did not bury their dead as needed, which also did not affect their health. So Brennus began negotiations with the Romans, urging them to surrender. He also noted that in exchange for the ransom, he could leave the city himself. The leaders of the Romans, who were waiting for the relief of Camillus, initially refused, but because of the pressure of their people, they finally had to agree. Brennus and the tribune, Quintus, the Superintendent, sat down for talks and, after negotiations, set the ransom amount to one thousand pounds of gold. Here, however, the Romans awaited another humiliation. During the weighing of gold that took place during the payment of the ransom, it became apparent that the Galls had provided forged weights that were heavier than they should have been. When the Romans pointed this out, Brennus just laughed and threw his sword on the scales, saying “Vae victis,” or “woe to the defeated.”

Paying the ransom to Senones in exchange for leaving the city was a humiliation for the Romans, but Livy claimed that eventually no tribute was paid because, during a quarrel when weighing gold, Camillus appeared at the head of his army. He told me to take gold and stop all fairs. Brennus tried to object, claiming that the agreement had already been concluded, but Camillus stated that the military tribune could not make such a decision without his consent, because according to Roman law if a dictator was chosen, all other officials could act only on his order because he stood at the highest hierarchy. So since the military tribune had an agreement with the Gauls without his knowledge, he had no legal force. Then Camillus challenged Gallom and defeated them in two battles. Liwius writes that it was a crushing defeat for Senones, and it gave Camillus himself much fame and prestige:

At the first encounter, therefore, the Gauls were routed with no greater difficulty than they had found in gaining the victory at Allia. They were afterwards beaten under the conduct and auspices of the same Camillus, in a more regular engagement, at the eighth stone on the Gabine road, whither they had betaken themselves after their defeat. There the slaughter was universal: their camp was taken, and not even one person was left to carry news of the defeat. The dictator, after having recovered his country from the enemy, returns into the city in triumph; and among the rough military jests which they throw out [on such occasions] he is styled, with praises by no means undeserved, Romulus, and parent of his country, and a second founder of the city.

– Titus Livy, Ab urbe condita, V.XV

Diodor Sicilian gave a slightly different version of the events. According to him, the Senones spent the first day after the battle of Alia on the battlefield, cutting off their heads, which, according to Diodor, was their custom. Then they spent two days camping outside the walls of Rome, whose inhabitants panicked because they thought that all their army had been destroyed. Many Romans fled the city, while leaders decided that food, gold, silver and other goods should be taken to the Capitol, which was turned into a defensive camp. At first, the Senones did not try to break into the city, because they thought that the noise coming from it meant that the Romans were preparing an ambush. Eventually, on the fourth day, they broke down the gates and invaded the city they had plundered, although Diodorus claimed that they had not harmed the civilians who remained in it. Then for several days they attempted to capture the Capitol by storm, but each time they were repelled, suffering heavy losses. The Gauls understood that they would not conquer the hill by storm and decided to carry out the siege.

Meanwhile, the Etruscans invaded Wejów lands, capturing slaves and spoils. Roman soldiers who took refuge in those areas ambushed them and crashed them. At the same time, they captured their camp, regained their plundered property, freed prisoners of war and acquired a huge amount of weapons. This victory increased the morale of the Romans, who began to regroup their forces, expanding them to include men who had fled Rome. They quickly decided to take Rome from the hands of the Gauls. A Roman soldier, Kominius Poncjus, sneaked to the Capitol to tell the defenders that the Roman army was waiting for a counterattack. Interestingly, Diodorus does not mention Camillus at all in his account. Pontius was to cross the Tiber and reach the Capitol, climbing a steep cliff. When he passed his message to the besieged, he returned to the lands of Wejsu along the same path. However, the Gauls had to find traces of his climbing, because they tried to get to the Capitol in the same way as Pontius. The Romans, because of the steepness of this place, did not guard it very closely and, as in Liwius’s account, they were saved from defeat by the “intervention” of the holy geese of Juno. After this event, the Romans began negotiations with Gauls, who at the price of a thousand pounds of gold, agreed to leave the city and withdraw from the Roman territories. After paying tribute to them, they kept their word and left. On the way back, however, they were attacked by the Etruscans on the Trauska plain and completely destroyed.

Plutarch, in turn, presented a much more dramatic picture of the capture of Rome. The Gauls arrived in the city three days after the victorious battle. They found open gates and vacant walls. They were to enter the city through the Kolin Gate. Brennus left some of the warriors near the Capitol to stop his crew from attacking and went to the Roman Forum. There, the Senones were surprised to see ancient Romans sitting in front of their houses, dressed in the best robes and with signs of former offices. Initially, the Gauls were afraid to approach and touch them, considering them to be supernatural. In the end, one of them gained courage and stroked the chin of one of the Romans. He hit him in the head with his stick in reply. The Gauls went on a rampage, they began to kill everyone who fell into their hands, not sparing the women and children who remained in the city. They also plundered houses and initiated fires which were to last for several days. They also attempted to storm the Capitol, but they failed. Plutarch also wrote that the Gauls entered Rome in February (i.e. February 13) and the siege of the Capitol lasted seven months.

According to Plutarch, part of the Gauls reached Ardea. Camillus, who was there, was prepared for this and broke their forces. As news of this victory spread, volunteers and remnants of the Roman army from Alia arrived from neighbouring regions and cities. They all wanted Camillus to become their leader and lead them to Rome. He refused, arguing that he was coming into exile and could become a leader only with the consent of the Senate. Plutarch also repeats the story of Pontius, who sneaked into the Capitol and obtained permission from the Senate to assume the role of a dictator Camillus. Together with allied troops and Roman forces, Camillus was to have about 20,000 soldiers under him.

After the episode with the Capitoline geese, the Gauls were less and less eager to besiege the hill. They were short of food and worried about rumours of Camillus’s army that were marching on Rome. Seon was also afflicted by diseases because they camped among the ruins and did not bury the bodies of those killed, which began to rot. Breathing was also hampered by the wind, which was constantly blowing ashes. They also warmed because of the Mediterranean heat, which they were not used to. For these reasons, the death rate in the Gallic army was very high, and everywhere in their camp lay the bodies of the dead, which could not be buried.

However, the defenders of the Capitol did not receive any messages from Camillus, because the Gauls carefully guarded the entire hill. Hunger worsened the situation. In the end, they felt cheated and decided to pay Senones a ransom in exchange for leaving the city.

When Camillus arrived in Rome, he ordered all gold to be removed from his weight and told the Galom that the ransom payment agreement was illegal because he, as a dictator, did not agree to it. The Gauls tried to object and there was almost a fight between them and the Romans. Bloodshed was only stopped by the fact that both armies could not develop battle ranks in the ruined city. Eventually, Brennus took his warriors and left Rome at night. At dawn, however, they were caught up by Camillus. The battle ended with a Gallic pogrom. The survivors who escaped the massacre were mercilessly hunted down and killed by the inhabitants of the surrounding cities and villages.

News of the capture of Rome by the Gauls even reached Greece. Plutarch mentioned the inaccurate history recorded by Heraclides of Pontus and Aristotle. When the latter wrote about the capture of Rome by the Gauls, he stated that the city was saved by “a certain Lucius”, not Camillus.

Contemporary controversies

Reports about the battle of Alia and the plunder of Rome were written several centuries later, and their credibility is questionable. This is especially evident in the discrepancies between Livy and Diodorus regarding the plunder of the city.

Information about the city’s reflection by Camillus is perceived by many contemporary historians as an addition to the story, since neither Diodorus Sicilian nor Greek historian, Polybius, mentioned it. Diodorus stated that the Gauls were defeated by the Etruscans on the Trauska plain (a place unidentified to this day) when they returned from southern Italy. Strabon wrote that the Gauls were defeated by the inhabitants of Cera (the Etruscan allied city with the Romans, where the vestals had found refuge), who also recovered gold, which the Romans paid tribute to Senones in exchange for leaving the city. Thus, it contradicts the version that Camillus did not allow the payment of the ransom. As already mentioned, Plutarch claimed that according to Aristotle, Rome was saved by “a certain Lucius”. This may refer to Lucius Albinius, who helped the vestal on his way to Cera. The role that the inhabitants of this city played in defeating the Gauls is unclear. It cannot be ruled out that it was larger than Roman sources describe.

The question is also what the Senones did at all in central Italy. Diodor Sicilian wrote that the Gauls came to Italy because they were looking for new lands because, in their former homeland, bad conditions prevailed. So they armed their youth and sent them to look for new territory to settle. That is why they invaded Etruria and plundered the areas of Kluzjum. However, some consider this doubtful. Attention is drawn to the fact that all sources mention only troops of warriors and there is no word about the presence of women and children among them, which is characteristic of migrating peoples looking for new lands to settle. Therefore, it cannot be excluded that the Gauls who conquered Rome were mercenaries. A few months later, the tyrant of Syracuse, Dionysius I, hired Gallic mercenaries for the war he fought in southern Italy. That would explain why the Senones wandered south. It is also likely that they might have been smashed on the way back.

It is also possible that the Gauls came to Clusium because they were rented by one of the two political factions that were fighting for power over the city. The other party could then ask Rome for help, which became the source of the entire conflict, and the story of Arruns, jealous of their seduced wife, could be a mere myth.

Consequences of the invasion

The defeat of Alia and the plunder of Rome were severe and humiliating defeats for the Romans. It also weakened his status in Italy. The defeat emboldened other Italian peoples with whom Rome had to wage war for the next thirty-two years to regain and consolidate its position. As a consequence, they led to a significant deterioration in Rome’s relations with the Latin League.

A few years after the ransacking of Rome, the city was surrounded by new walls, which were built of hewn stone, imported from the territory of the Wejhes. It was a great undertaking because the new walls were eleven kilometres long. The original wall was made of local tuff, which was of poor quality and easily cracked and crumbled. The new wall was of much better quality, although the stone for its construction was harder and therefore more difficult to process.

The plundering of Rome was also rooted in the Romans’ long and deep fear of the Gauls. In 350-349 BCE, unidentified Gauls, who were probably marauders, invaded Latium twice. During the second invasion, Marcus Valerius Korwus fought a Gallic leader and killed him:

And at that time vast forces of Gauls had encamped in the Pomptine district, and the Roman army was being drawn up in order of battle by the consuls, who were not a little disquieted by the strength and number of the enemy. Meanwhile the leader of the Gauls, a man of enormous size and stature, his armour gleaming with gold, advanced with long strides and flourishing his spear, at the same time casting haughty and contemptuous glances in all directions. Filled with scorn for all that he saw, he challenged anyone from the entire Roman army to come out and meet him, if he dared. Thereupon, while all were wavering between fear and shame, the tribune Valerius, first obtaining the consuls’ permission to fight with the Gaul who was boasting so vainly, advanced to meet him, boldly yet modestly. They meet, they halt, they were already engaging in combat. And at that moment a divine power is manifest: a raven, hitherto unseen, suddenly flies to the spot, perches on the tribune’s helmet, and from there begins an attack on the face and the eyes of his adversary. It flew at the Gaul, harassed him, tore his hand with its claws, obstructed his sight with its wings, and after venting its rage flew back to the tribune’s helmet. Thus the tribune, before the eyes of both armies, relying on his own valour and defended by the help of the bird, conquered and killed the arrogant leader of the enemy, and thus won the surname Corvinus.

– Quadruptor, fragm. 12 (Peter), quoted by Aulus Gellius, “Noctes Atticae”, 9/11/9/11/09.

After the duel, there was a battle in which the Romans won. Polybius wrote that they had made peace with the Gauls who had not returned for the next thirty years. Although Rome defeated Senones at the Battle of Sentinum during the Third Samnite War, widespread fear of the Gauls continued. In 228 BCE, 216 BCE and 114 BCE, the fear of their invasions were so strong that the Romans made human sacrifices, burying a few Gauls and Greeks alive, although human sacrifice was not a Roman custom. Probably, however, they were supposed to beg the gods for protection against another Gallic invasion.