The purpose of this text is to introduce a little symbolism and also to take a closer look at one of the most terrifying punishments of the Roman judiciary. Poena cullei, or the so-called punishment of the sack, is most commonly known as the one suffered by patricides in ancient Rome. The condemned man was sewn up in leather sackcloth with the company of four animals – a dog, a monkey, a snake and a rooster. Then the sack, along with the live contents, was thrown into the river. But this is just one of the harsh faces of Roman justice administered through poena cullei. What else do we know about it?

Although nowadays it is most often referred to as the penalty for patricide, in practice it was a sentence issued to a person responsible for killing any of his immediate family. The course of poena culleiwas not always the same. The first mentions of her say that the unfortunate man was sewn up in sackcloth with snakes only. It was only with time that the four animals I mentioned above appeared and were modified. During the reign of Emperor Hadrian, there was also an alternative to the punishment of the bag – the murderer could die by throwing it to wild animals. Naturally in the arena, to the delight of the public.

In the nineteenth century, historian Theodor Mommsen set out to re-examine the intricate history of punishment that many think of as a ritual rather than a mere administration of justice. It is also not surprising that the various descriptions are not consistent; the punishment must have evolved over nearly seven centuries (from the 1st century BCE to the 6th century CE). But where did the idea for sewing the convict in a leather sackcloth, in addition to such an unusual company come from?

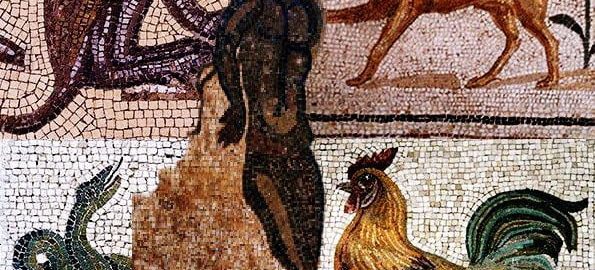

An analogy is sought in the ritual called procuratio prodigii, i.e. the so-called drowning of monsters (Maciej Jońca writes more about this in the article Poena cullei. Kara czy rytuał?). It referred to the removal of beings, creatures that were crippled or distorted. It was believed that these were obvious signs that on the god-people plane things were not going well, and by getting rid of such peculiarities, good order and order would return. At this point, the image begins to clear slightly. The killer of a relative must have been an unscrupulous creature, not fully rational. Therefore, it was necessary to get rid of it, so that it would not be a weak and dangerous link in the bond with the gods. Here, too, the issue of the selection of animals that were sewn up in the sackcloth along with the convict begins to become clearer. The monkey was associated with low instincts, it was considered a caricature of a man who did not know exactly what he was doing. The rooster symbolized the lack of attachment to anyone and anything. The dog evoked respect in its own way – it was he who travelled the world with Hecate, he guarded in Hades, and his head was often portrayed as Charon’s carrier. The serpent, on the other hand, was identified as an ancient creature. Deprived of ears and limbs, he crawled around the world and killed. The monstrous Medusa had this snaky swirl on her head. On the other hand, it was the snake who looked after the welfare of the family. Perhaps it is no wonder then that he should punish with death the one who committed the murder of someone from his own family.

Before the execution, the condemned man was put on a sack made of wolfskin, which was to symbolize his animal, feral nature. Wooden shoes were put on his feet, because it was believed that wood was an insulating material, cutting off the murderer from the ground. Before sewing the bag, the executioners whipped the naked unfortunate with poles the colour of blood, some stories also mention rods. The very process of throwing the sack into the river was also symbolic – returning to the water from which you were born (a common denominator is sought with the amniotic waters). The victim could not be buried under any circumstances; the final fulfilment of the punishment was the mixing of the bones of the convict with the bones of the accompanying animals.

As we can see, poena cullei does not have a single and clearly defined pattern, it was not punished for one specific offence, in history, it went and returned, it was accompanied by various alternatives. There is no doubt, however, that each version produces a strange mixture of horror and fascination in us. Many wonders to what extent the punishment of the sack should be called another form of administering justice, and to what extent a disturbing ritual, which should also be a warning to all viewers. The very fact that the punishment could have been inspired by the ritual elimination of cripples and uneducated organisms prompts some reflection. Here, however, is nothing but another secret of the invaluable and vast world and history of the ancient Romans.