The Parthian War (114-117 CE) proved to be a spectacular, albeit impermanent, success of Emperor Trajan (98-117 CE). In daring campaigns, vast tracts of land were briefly subordinated to the will of the Eternal City, including Armenia and Mesopotamia within the borders of the empire.

Being the first Roman commander to cross the Euphrates and Tigris basins, reaching the shores of the Persian Gulf, Trajan had the opportunity to visit places much older than Rome, dating back to the times of 3,000. BCE One of them was Babylon, the legendary pearl of Mesopotamia and one of the most important cities of the ancient Near East, the capital of such famous rulers as Hammurabi (1792-1750 BCE) or Nebuchadnezzar II (604 – 562 BCE), the great love of Alexander the Great (336 – 323 BCE), which had the honor of becoming the capital of his new empire. Roman historian Cassius Dio, who lived in the years ca. 163 – 229 CE, in his work entitled Historiae Romanae (Roman history), gave a short, but extremely compelling episode of Emperor Trajan’s visit to the city. Before discussing it, it is necessary – in order to carry out a comparative analysis of the emperor’s expectations and the image he finds – to outline the image of Babylon ruling in the Greco-Roman world.

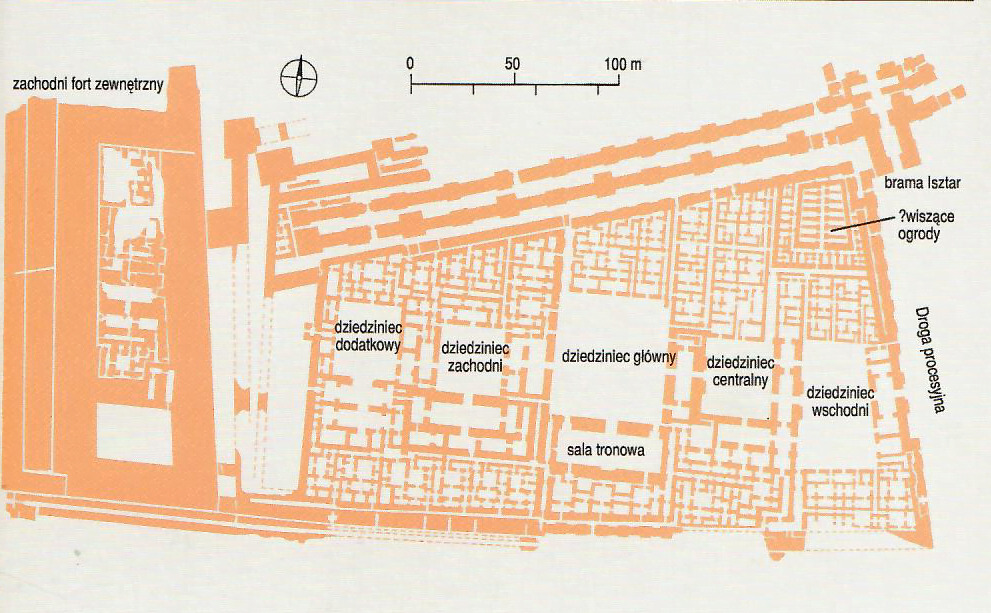

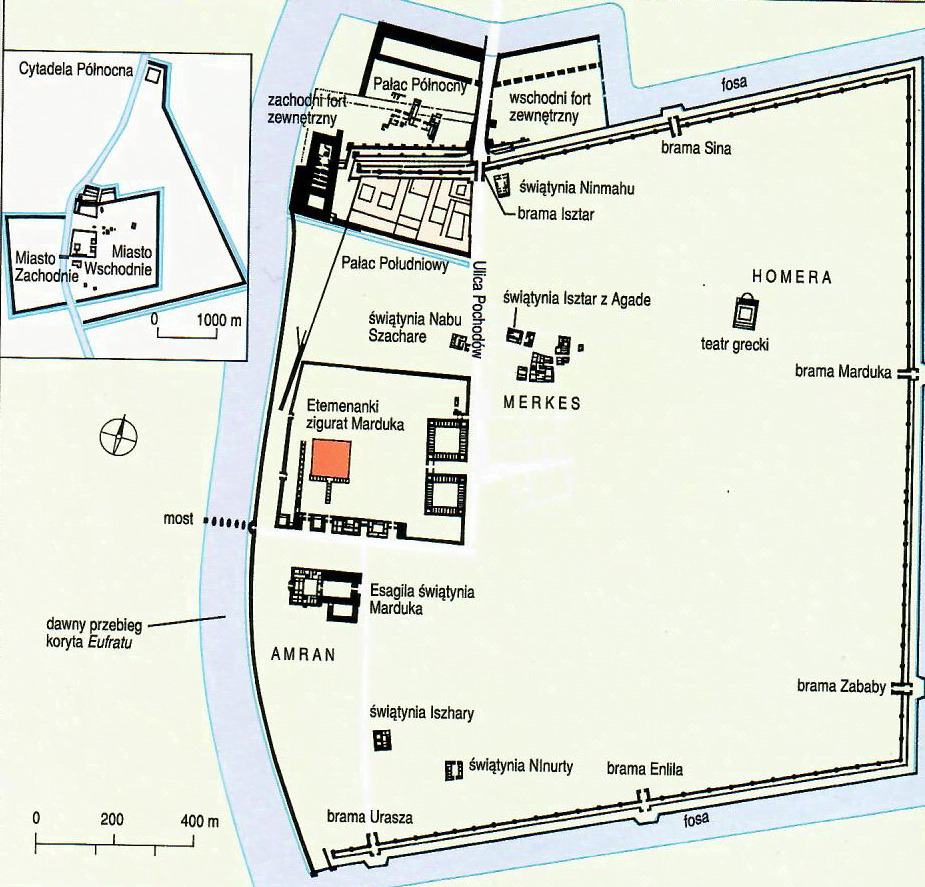

His most important description for this account, due to its direct connection with the story of Alexander the Great, a special authority for Trajan, who himself strove to repeat his unparalleled work, is the work of Quintus Kurcjus Rufus, preserved to our times (no certain data, ca. 2nd century CE) – Historiae Alexandri Magni (History of Alexander the Great). Moreover, it represents a version of history developed in ancient schools, and therefore quite commonly known to the Greco-Roman elite. According to her, it was not the fabulous wealth of Darius III, but the beauty and age of the city that captured Alexander’s attention. It was to admire the walls built of baked bricks combined with asphalt, 17 meters high, and so wide that two chariots could easily move along them side by side. There were plenty of miracles of technology foreign to the Greeks. The banks of the Euphrates flowing through the city were strengthened by huge embankments, behind which there were extensive retention reservoirs, protecting the city against the sudden withdrawal of the river from the bed. Above it, a stone bridge has been erected connecting the two districts of the city – the western and the eastern one, praised by ancient authors.

In turn, a mighty fortress towered over the city, at the top of which were the legendary Hanging Gardens, full of lush fruit trees with impressive trunks up to three meters wide. They were supposed to give the impression of a forest naturally growing on the mountain, an image completely surreal for the plain and treeless landscape of Mesopotamia, and in addition blended into the urban development of Babylon. At this point, we should also mention other ancient authors writing about the wonders of the city, incl. Herodotus, Antipater of Sidon, Diodorus Siculus, Strabo, Arrian, Plutarch. Interest was also aroused by the magnificent Etemenanki ziggurat, identified with the tomb of the legendary Belos. In the case of this monument, it was in ruins as early as Alexander’s time. Nevertheless, the shape of the stepped pyramid and its impressive size still aroused admiration for the craftsmanship of the builders. Such a beautiful picture of the city certainly created high expectations for Emperor Trajan, who was apparently unrecognized or simply unbelievable in the contemporary geographical literature about the current state of the city.

Babylon came under Roman rule as a result of the Second Mesopotamian Campaign in CE 116, when an invasion flotilla sailed down the Euphrates to conquer the Party’s heart – Lower Mesopotamia. No significant problems were encountered, the Romans were in the hands of Babylon, Seleukia and Ctesiphon, in which the throne was seized and the daughter of Osroes I (109–129 CE), the ruler of the Parthians, was seized. The emperor continued his victorious march – or rather, voyage – all the way to the shores of the Persian Gulf. On the way back, he visited Babylon, where the first disturbing information reached him. The situation at the front turned out to be critical, in most of the subordinated lands, and it was a huge area – from Armenia and Caucasian Albania, through Upper Mesopotamia and part of eastern Syria, to Lower Mesopotamia – revolts of the local population broke out. Roman garrisons were forced to flee or simply murdered, in both cases control of the main cities was lost. The universality and synchronicity of their outbursts, as well as the moment when it happened – the presence of Trajan in the very south of Mesopotamia, in the isolated, marshy watershed of the Tigris and Euphrates – strongly supports the hypothesis of the triumph of enemy intelligence. The party went offensive for the first time in this war.

Despite these events, the emperor completed his visit to Babylon. It was not only the urgent situation at the front that forced him to leave quickly. Also, what was left in the city did not speak for a longer stay in the unfulfilled capital of Alexander the Great. This situation is best illustrated by quoting the source material itself.

Trajan ascertained this in Babylon. He had taken the side-trip there on the basis of reports, unmerited by aught that he saw (which were merely mounds and stones and ruins), and for the sake of Alexander, to whose spirit he offered sacrifice in the room where he had died

– Cassius Dio, Roman history, 30.1

Expectations were beyond reality. The beauty of Babylon, both imaginary and real, celebrated by ancient creators, is long gone. Its place was taken by ruins of dubious glory. What was responsible for the existing condition of the city and the resulting occupation of the emperor?

Babylon’s fame was primarily due to the investments of the Chaldean rulers, who made the city the capital of the vast but short-lived New Babylonian Empire (626-539 BCE). During their reign, it experienced its greatest episode in history, and at the same time the best known by us. The source of this glory and riches was the seizure of power over the territories previously belonging to Assyria – Upper Mesopotamia, Syria, Phenicia and Palestine, the subjugation of which we know from the biblical history of the Babylonian captivity. Related to it is the unprecedented depopulation of Judea – the complete opposite of Assyrian deportations, which relocate different sections of the population while avoiding the creation of depopulated areas. The long list of construction projects evidenced in the royal inscriptions of Nebuchadnezzar II easily reflects the scale of accumulated wealth and the momentum to expand the capital of the empire. It was during his reign that the great Etemenanki ziggurat was renovated, a new royal palace (the so-called Southern Palace) was erected, a stone bridge over the Euphrates (probably), the city walls were expanded, the most remarkable monument of which is the Ishtar Gate, which has survived to this day, and numerous conservation works were undertaken. repair works over other structures, mainly over the temples of numerous deities of the Mesopotamian pantheon. The fall of the city’s political independence (539 BCE), with Achaemenid Persia seizing power over the entire Middle East, began the slow and steady process of Babylon’s impoverishment. Despite the honorable position of one of the capitals of the great Persian empire, the city had to compete for a leading role in the country with other eminent urban centers (including Persepolis, Susa, Ekbatana). A brief episode (331 – 323 BCE) of ambitious plans to restore the city was to make it the capital of Alexander the great’s ephemeral empire, nevertheless even his favors did not influence the later Seleucid decision to move the capital, first to Seleuca on the Tigris and second to Antioch Syria, leading to the historic end of the role of Babylon as the capital. During the Parthian rule (141 BCE – 226 CE), the city’s population reached the level of about 20-30 thousand. inhabitants, which was still a considerable number, unfortunately much less than approx. 180 thousand. inhabiting them in the 6th century BCE. This significant reduction in the population must have had a negative impact on the condition of the city.

The degradation of buildings was a long and complex process, in which many factors were driving each other – the problems of construction belonged to one of them. The main Mesopotamian building material – dried brick – was both a blessing and a curse on the local buildings. Easy to handle, widely available, and therefore cheap, it allowed for quick and trouble-free erection of buildings, unfortunately requiring constant repairs due to the instability of the material. Failure to do so resulted in a relatively quick disintegration of the structure, on the ruins of which, due to the cost of removing the ruins, another building was erected, which in the process resulted in the piling up of houses, and thus entire towns. The result of these activities are artificial hills (Arabic: tall), characteristic for the landscape of contemporary Iraq and Syria, hiding in their guts the traces of ancient civilizations. Therefore, there are no preserved monuments of former Mesopotamian architecture – unlike in Egypt, they have been almost completely absorbed by nature and time. Fired brick was a more durable building material, but the limited access to fuel – wood was a valuable material due to its lack in Mesopotamia – eliminated its widespread use. Nevertheless, it was used in monumental structures, such as temple or palace complexes, and as a reinforcement for extremely sensitive building elements. Durability and limited supply contributed to its re-use, which attracted the specter of material looting to the preserved buildings. This was the case with some of the projects of Nebuchadnezzar II – incl. Etemenanki zigguratu and the royal palace. Archaeological research has shown that the palace in question, unused by the central administration since its abandonment by the Seleucids, was developed in the 1st century BCE and stripped of valuable materials by the local population, using its space even for burial purposes (!). Consequently, it is uncertain whether Emperor Trajan visited the actual place of Alexander’s death. Who of the locals might know which of the looted, half-ruined palace rooms once constituted the bedrooms of the great conqueror? One of the most important Hellenistic monuments in Babylon, if not the only significant one, was a theatre erected for the local Greek-Macedonian diaspora by Alexander the Great or one of his successors, later restored by the Parthians (due to their Philhellenism, which persisted until the first military clashes with Rome).

The urban planning projects of the new rulers of the region, the Seleucids and the Parthians, turned out to be key in the process of the city’s degradation. Founded in its vicinity, Seleukia on the Tigris (305 BCE) and Ktezyfont (141 BCE) dominated the region as new urban centers of the ruling dynasties, and therefore of the state administration. Babylon became for them a natural source of people and raw materials, especially the aforementioned fired bricks. The problem is not limited to antiquity, at the dawn of the Middle Ages, the Arabs will use bricks from the Sassanid Ctesiphon to build Baghdad, thus continuing the Middle Eastern tradition of “recycling” materials. The same process affected numerous monuments of Roman civilization in the Middle Ages and the modern era. The outflow of inhabitants to more attractive urban centers, benefiting from the direct presence of the rulers, consisted of voluntary emigration and forced deportations (275 BCE to Seleuk on the Tigris). The definitive loss of the city’s capital function led to the limitation and finally the suspension of royal investments, formerly generously flowing to Babylon.

In addition to architecture and urban planning, cultural, political and military factors also contributed. Since the fall of the city’s political independence, the process of the disappearance of the Mesopotamian culture, and thus of the traditions linking the population with the place, has been steadily progressing, as are the other factors. In favor of Aramaic, the lingua franca of the then Middle East, the use of Babylonian in everyday life was discontinued, the last cuneiform tablets were issued at the end of the 1st century CE, and the extinction of the Marduk cult in Esagili – crowning the death of an ancient civilization – in the 3rd/4th century CE, the work of the Progressive was completed by acts of repression by the authorities (the results of rebellions during the reign of the Achaemenids – Darius the Great and Xerxes I) and the cases of the plunder of the city (310/9 BCE during the Diodeo Wars). To make matters worse, the city was likely to be subjected to cruel preventive persecution in 117 CE, designed to pacify the Mesopotamian Jewish diaspora, as only Eusebius of Caesarea mentions in Historia ecclesiastica (Church history).

Even before the imperial visitation, efforts were made to answer the question of what led to the fall of Babylon’s glory. Strabo’s Geographica hypomnemata – living in the years 63 BCE – ca. 21/25 CE – provides his own conclusions. Both the Parthians and the Macedonians were to be responsible for bringing to ruin the city found by Alexander, already then having its best times behind them. Contemporaries saw the fateful decision of the Seleucids to create a new capital on the Tigris, the aforementioned Seleuca. The state of Babylon at the time of the author, struggling with the problem of depopulation and ruins, is reflected in the punch line quoted in his description – “The great city is a great desert“.

The loss of people, funds and materials, with the constant need to renovate the buildings, led to the rapid abandonment and destruction of the city’s surviving buildings. The loss of the prerogatives of the city, resulting from being the capital of the previous conquerors, and the related insignificant role in the administrative systems of new empires strengthened the processes taking place. The main factors, already partially observed by the ancients, responsible for this situation were the urban projects of the Seleucids and Parthians. The turmoil of war over the centuries did not omit this place as well. The result of these processes was the image of Babylon by Emperor Trajan – a ruined and depopulated city with a wonderful past.