The city walls of Pompeii were not built by the Romans, but by a local Italic people, an Osco-Samnite population, long before the formal incorporation of the city into the Roman state after the Social War (1st century BC). During this war, the Samnite fortifications allowed Pompeii to resist – perhaps with success – the legions of Lucius Cornelius Sulla. What did the fortifications look like and what do we know about their centuries-old history?

In ancient times, the first thing people could see as they were approaching the cities in Italy were the city walls. This was also the case of Pompeii, which we usually do not associate with fortifications, as we focus all our attention on the interior of the city. The walls can be partly seen immediately at the entrances to the archaeological site, but they are best preserved on the north side of the city.

The exploration of Pompeii’s fortifications began in the first half of the 19th century, when the entire area occupied by the ancient city was bought by the state – the Kingdom of Naples – thanks to the efforts of Caroline Bonaparte, wife of Joachim Murat, king of Naples (1808-1815). However, the complete unveiling of the walls was made only in the 1930s by Amedeo Maiuri, the well-known archaeologist, director of Pompeian excavations in the period 1924-1961.

The Pompeian city walls preserved to our times are a pre-Roman structure, build in the Samnite period, when the region was inhabited by an Osco-Samnite population. Like many other Italian communities and cities, Pompeii formally and actually became Roman only after the Social War (90-87 BC). Earlier, the city had the status of a Roman ally, which means that it was not directly part of the Roman state, it had local autonomy, and its inhabitants, Italics, did not have Roman citizenship. In the Samnite period, a fully developed urban structure of Pompeii was created, largely modelled on Hellenistic cities; the city grew according to a certain plan adopted by local authorities, not spontaneously. Many houses, including large residences (like the House of the Faun – Casa del Fauno), and monumental buildings such as temples, baths and one of the two theatres (Teatro Grande) were built during the Samnite period.

The walls that have survived to this day were built in the 4th or at the turn of the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE, during the Samnite Wars. But their history goes back to earlier times, the beginnings of Pompeii, founded as a small settlement, most probably by the Osci, in the 8th-7th cent. BC. Archaeologists have distinguished three main construction phases of Pompeian city walls. Interestingly, their course was almost unchanged throughout their existence. Initially, a large part of this area may have been occupied mainly by gardens, orchards and vineyards.

The oldest identified remains of the walls in pappamonte (soft lava) date back to the beginning of the 6th century BCE (phase A). The phase B walls were built at the end of the 5th century BC. These double walls made of blocks of limestone were stronger, but still relatively low, their outer wall being about 4 m high. It’s not entirely certain who they were built by. According to one of the hypotheses, the phase B walls would have been the work of the Oscans, modelled on the Greek art of fortifications. The Greeks were present in Campania from the 8th century and their influence was very strong in this region. According to another hypothesis, these walls were erected by the Etruscans, masters of a large part of Campania in this period (7th-5th centuries BC). Today, the most widely accepted opinion is that the B-phase walls were built by the Samnites who arrived in Campania and settled there in the 5th century BC.

The Samnites also rebuilt and strengthened the existing walls during the wars with the Romans at the end of the 4th century BCE (phase C walls). Initially, it was a single wall made of limestone blocks, about 10 m high and 0.8 – 1 m thick, reinforced on the town side with an earth embankment (agger). During the Second Punic War, an internal wall of tufa was added. It was a few meters higher than the outer wall. The space between the two lines of walls, about 5 meters wide, was filled with earth, and a new inner agger, from the town side, was added, on the top of which a road for guards and troops run.

The enceinte of Pompeii was renovated and strengthened at the end of the 2nd and early 1st century BC. During the Social War, Pompeii sided with the Italian allies and resisted the besieging Roman troops under the command of Sulla (in 89 BC). The city may have capitulated, but it is not entirely certain. Some scholars assume that Sulla did not capture it during bellum Italicum. They argue that during the Civil War between Sulla and Marius Pompeii sided with the latter and that Sulla besieged the city a second time in 82 BC. Only then would he have forced Pompeii to surrender. One thing is certain: Pompeian walls did not suffer much damage. Sulla punished the city for resistance, like a dozen other Italian cities, establishing a Roman colony there. When Roman veterans were brought there (80 BC), Pompeii actually became a Roman city.

The length of the walls surrounding Pompeii is 3.25 km. In their structures, there were 7 or 8 city gates and 12 towers. The names of the gates used today do not correspond to the ancient ones. The original Oscan names of some of the gates are known from the painted inscriptions from the period of the Social War. The towers had numbers, which we also know from the inscriptions. In the north, near the place the Vesuvian gate was located, traces of missiles from the period of the siege by Sulla can still be seen.

- Partly reconstructed Tower XI – view from the city side, Via Mercurio.

- Porta Marina – Sea Gate, present entrance to the excavation site from the Circumvesuviana Railway Station “Pompei Scavi – Villa dei Misteri”.

- Nola Gate – Porta di Nola (on the eastern side of the city).

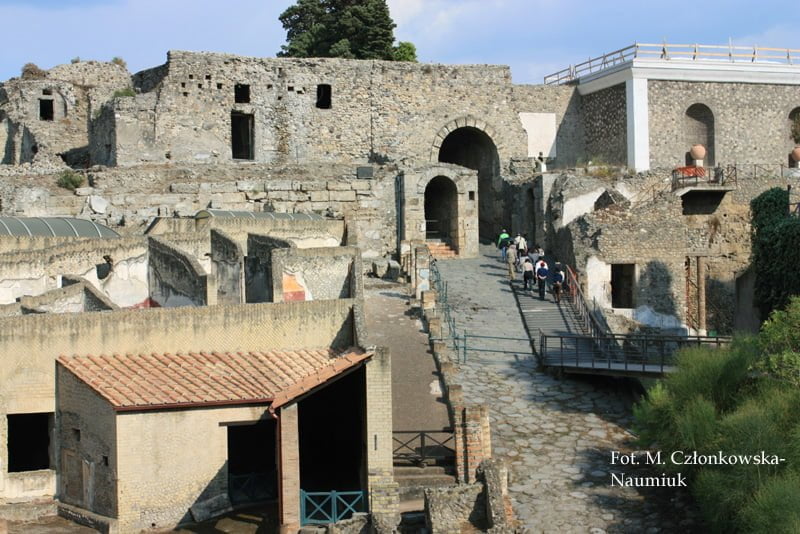

- View of the city from the north

- Tower XI and the city wall, view from the north. The towers were covered with white plaster imitating large stone blocks.

- Partly reconstructed Tower XI – view from the city side, Via Mercurio.