Chapters

The Marcomannic Wars is a series of wars that the Roman Empire waged in the years 167-180 CE with barbarian tribes living in the areas neighbouring its northern borders. During the entire period of the conflict, many ethnically different barbarian tribes took part, such as the German Longobards, Marcomannians, Narists, Quads or Boers, but also the Celtic Kotyns, the Danish Kostobok and finally the Sarmatian Iazyges and Roxolani.

At various times in this period, barbaric tribes crossed the borders of the Empire on the Rhine and the Danube and carried out extremely bloody, raiding raids deep into its territory, which eventually gave rise to the feedback and brutal reaction of the Romans. However, the most active role among the tribes attacking the Empire was played by the German Marcomanni (hence the “Marcomannic Wars”) and the Quadi supported by the Sarmatian Iazyges. These three tribes throughout the entire Marxian wars gave rise to the Empire and the subjugation of these three tribes required the Empire’s greatest military effort1.

The Marcomannic Wars were mainly during the reign of Emperor Marcus Aurelius and were fought with varying degrees of success for Rome. After initial defeats and pushed to the defensive (167-170), however, the Empire managed to take the initiative and the next period of the Marcomannian wars (171-180) was characterized by the transfer of major warfare to the enemy’s territory by Rome. The impermanence of the coalitions concluded by the barbarian tribes to attack the Empire, concluding peace after their defeats only so that, when the opportunity arises, immediately break it and fight again, causing the conflict to be characterized by varying intensity and sudden twists. Let us present, therefore, one such twist in the ongoing conflict, in which the participant (alongside the Romans) was the Germanic people of the Quadi2.

Briefly about the Quadi and their participation in the Marcomannic Wars

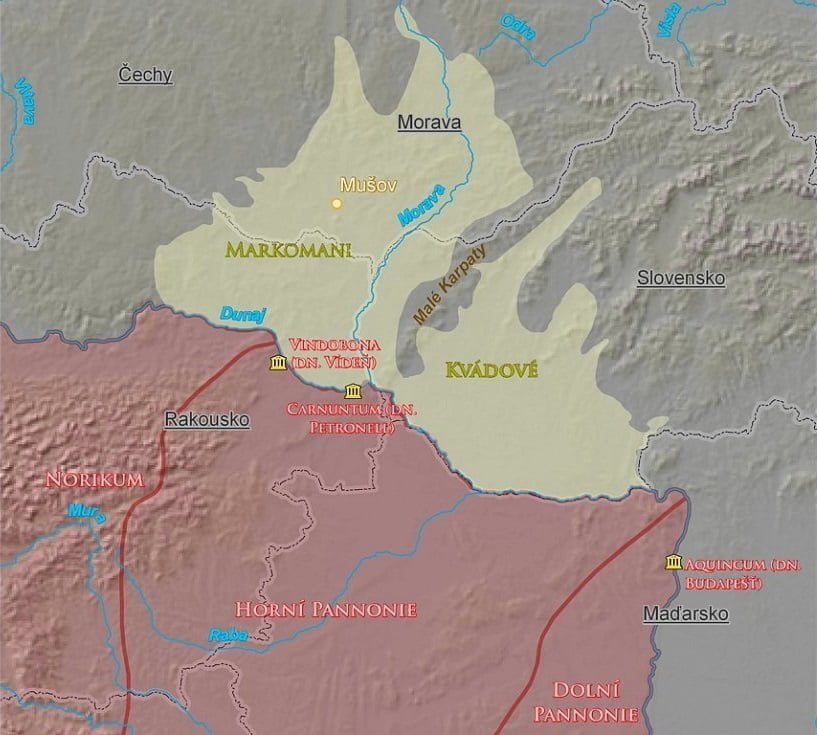

The Quadi (also known as Suebi) were a Germanic tribe that originally lived on the Main River. However, war campaigns conducted by Emperor Octavian Augustus to conquer and join Germany to the Empire of the lands of Germania located between the Rhine and the Elbe caused, however, that at the beginning of the first century CE the related Marcomanni and Quadi tribes left their headquarters on the Main and moved eastwards, i.e. to the north of Lower Austria, southern Moravia and southwestern Slovakia. As for the Quadi themselves, on the eve of the outbreak of the Marcomannis wars, they bordered on the west with a related tribe of Marcomanni, as well as with Germanic Narists located at that time over the central Danube at the mouth of the Morava. It is assumed that the border between Marcomannicy and Quadi was the Little Carpathians range (see Fig. 1). In turn, the Quadi bordered on the east with the Sarmatians (Sarmatian tribe of Iazyges) and Germanic Boers. Whereas in the north and northeast with the dependent Celtic tribe of Gotini. And finally, the southern border of the Quadi settlement was marked by the borders of the Roman Empire3.

Author of quotation: Unknown. Source: https://breclavsky.denik.cz/zpravy_region/obdobi-zmen-keltove-odchazeji-zacina-era-germanu-20120710.html.

During the Marcomannic Wars, the Quadi were one of their most active participants and one of the fiercest opponents of the Romans. The Marcomannic Wars themselves began in 167 with the invasion of the Upper Pannonian Germanic tribes of the Lombards and Obi and the parallel invasion of the neighbouring Pannonia province of Noricum by Marcomanni, Quadi and Jazyg assisted by several other minor tribes. In a fairly large battle that took place in Pannonia, the barbarians were beaten by the Romans and in the same year they withdrew from Roman territory asking for peace. Peace was concluded with a barbarian delegation representing as many as ten tribes who arrived for its conclusion, which only then showed to the Romans that the raiding invasion was not accidental but was a coordinated action of barbarian tribes aimed at the Empire. The concluded peace did not last long, however, as the next year, i.e. 168, there were further attacks by barbarians on the northern borders of the Empire. Of course, the Quadi also took part in these attacks. The invaders were repulsed. However, the Quadi lost their current King Markomar in the fighting. For a moment, there was peace on the part of the Quadi (cooperating with Marcomannians). The next 170 years went down in the history of the Empire as extremely bloody and marked by disasters. In the spring of 170, the Marcomanni and Quadi family anticipated the counter-offensive prepared by the Romans and abolished three Roman legions in a quick rally. The losses of the Romans are about 20 thousand. of the fallen and the borders of the empire open to barbarians. After this success, the attackers felt so confident that they crossed the Julian Alps and approached the border of Italy alone besieging Aquileia (an ancient city near present-day Venice). A well-fortified and supported seaside, it resisted the siege (Fig. 2). Then the attackers rolled her siege to attack and capture the small city of Opitergium (today’s Oderzo). Opitergium was first plundered and then destroyed. Barbarians murdered the entire Opitergium population with4. The year 171 is considered to be the beginning of the Roman counteroffensive and the consistent removal of invaders from its territory by the Romans. In the same year, the Romans beat somewhere over the central Danube Marcomanni and Quadi returning from a plundering expedition and taken from the spoils they transported. As a result of the emperor’s intervention, the spoils taken away from the Roman army by the barbarians were returned to their owners, which, due to the unusual nature of such conduct in the war, probably was the reason for the fact that the ancient source5noted it. After fierce battles with the Romans, the Quadi asked for peace. Perhaps it was then that the Romans gave the squares of the dependent King Furtis. The next year – 172 – brings the transfer of hostilities to the enemy’s territory. Having broken up the Marcomanni-Kwadzian alliance, Marcus Aurelius decided to pacify the Marcomannians. Soon they were beaten and in the same year peace was made with them (Fig. 2). Unexpectedly, however, the conflict with the Squares resumed. The most important reason for the renewal of the conflict was their banishment of King Furtis, given by the Romans. Instead, the Quadi chose their own king named Ariagaesus – belligerent for the Romans. After the selection, the barbarians turned to the emperor for his recognition. Being confronted with a fait accompli, Emperor Marcus Aurelius did not acknowledge Quadi’s arbitrary choice of the king. In addition, it turned out that despite the condition obliging the Quadi not to contact Marcomannicy, they provided, during military operations against the latter, help to consist in hiding on their territory their fugitive or wounded warriors. In addition, they failed to comply with the condition of returning all captive Roman captives and entered into a defence alliance with the Sarmatian Iazyges. Marcus Aurelius was still trying to negotiate with barbarians wanting to avoid a renewed conflict. He demanded from the Quads only to restore power to the overthrown King Furtis. However, they rejected the emperor’s demands. In response, the emperor set a high reward for providing him with living or dead King of Ariagaesus, and at the same time began warfare. In 173, the large-scale Roman offensive6was launched against Quadi (Fig. 2).

Author of quotation: Unknown. Source: https://www.archeologiemusov.cz/en/educational-trails-and-museums/educational-trail-1/panel-1/.

The miracle of rain and lightning miracle

Three legions were mobilized to fight the Quads, among which was the XII legion shifted from Melitene in Cappadocia, Asia Minor (currently Malataya in Turkey). The fights were bloody and fierce. In the summer of the same year, a battle took place, which probably took place somewhere on the border of the headquarters of the Quadi and Celtic Kotyns, i.e. a tribe neighbouring and subordinate to Quadi. During the battle, the Roman army was surrounded and at some point the struggle was close to defeat when suddenly an unusual event occurred that changed the fate of the battle. This event was confirmed in numerous ancient sources and went down in history as a “miracle of rain and lightning miracle” (or “wonder rain battle”)7. The most important ancient sources confirming them include: a short, though containing interesting facts, mention of Iulius Capitolinus contained in the work entitled Historia Augusta, a picturesque account of a Roman Greek historian, Lucius Cassius Dion Kokcejanus, contained in the work entitled Roman history and the equally picturesque account of the Christian bishop and historian Eusebius of Caesarea in Palestine contained in his work entitled Church history. It is worth mentioning that although the battle and the extraordinary events that accompanied it were confirmed by the accounts of the abovementioned of histories, however, their descriptions have not only common or complementary elements but also divergent elements as to the reason for the occurrence of these extraordinary events that accompanied the ongoing battle.

This is how the “miracle of rain and lightning miracle” was reported in the mention of Iulius Capitolinus8:

By his prayers he summoned a thunderbolt from heaven against a war-engine of the enemy, and successfully besought rain for his men when they were suffering from thirst

– Iulius Capitolinus, Marcus Aurelius Philosopher, 24, 4, in Historia Augusta

However, this battle of an unusual ending was described in work by Cassius Dio9:

(A great war against the people called the Quadi also fell to his lot and it was his good fortune to win an unexpected victory, or rather it was vouchsafed him by Heaven. For when the Romans were in peril in the course of the battle, the divine power saved p29 them in a most unexpected manner. The Quadi had surrounded them at a spot favourable for their purpose and the Romans were fighting valiantly with their shields locked together; then the barbarians ceased fighting, expecting to capture them easily as the result of the heat and their thirst. So they posted guards all about and hemmed them in to prevent their getting water anywhere; for the barbarians were far superior in numbers. The Romans, accordingly, were in a terrible plight from fatigue, wounds, the heat of the sun, and thirst, and so could neither fight nor retreat, but were standing and the line and at their several posts, scorched by the heat, when suddenly many clouds gathered and a mighty rain, not without divine interposition, burst upon them. Indeed, there is a story to the effect that Arnuphis, an Egyptian magician, who was a companion of Marcus, had invoked by means of enchantments various deities and in particular Mercury, the god of the air, and by this means attracted the rain.

– Lucius Cassius Dio, Roman History, LXXI, 8.

And finally the “miracle of rain and lightning” on the pages of Church history of the bishop and also the Christian historian Eusebius of Caesarea is as follows10:

It is reported that Marcus Aurelius Cæsar, brother of Antoninus, being about to engage in battle with the Germans and Sarmatians, was in great trouble on account of his army suffering from thirst. But the soldiers of the so-called Melitene legion, through the faith which has given strength from that time to the present, when they were drawn up before the enemy, kneeled on the ground, as is our custom in prayer, and engaged in supplications to God.

This was indeed a strange sight to the enemy, but it is reported that a stranger thing immediately followed. The lightning drove the enemy to flight and destruction, but a shower refreshed the army of those who had called on God, all of whom had been on the point of perishing with thirst.

This story is related by non-Christian writers who have been pleased to treat the times referred to, and it has also been recorded by our own people. By those historians who were strangers to the faith, the marvel is mentioned, but it is not acknowledged as an answer to our prayers. But by our own people, as friends of the truth, the occurrence is related in a simple and artless manner.

Among these is Apolinarius, who says that from that time the legion through whose prayers the wonder took place received from the emperor a title appropriate to the event, being called in the language of the Romans the Thundering Legion.

– Eusebius of Caesarea, Church history, V, 5, 1-5.

On the basis of the abovementioned ancient sources, it is likely that the following course of the battle of the Romans with the Quadi during the 173 summer campaign against them can be deduced. Well, it can be deduced from the description of Cassius Dion that the Roman army conducting war against the Quadi – which also included this from Melitene in Cappadocia, Legion XII – was surrounded by overwhelming opponent forces. We do not know whether the Romans’ position was due to the fact that they fell into the trap set by the barbarians or was the result of an inaccurate assessment of their own military capabilities involving the battle against a larger opponent in adverse terrain conditions. Either way, during the ongoing battle, the legionaries were surrounded by an outnumbered opponent. The fight was apparently in close quarters with tightly-knit ranks, as evidenced by a fragment of Diona saying that legionaries “bravely defended themselves by combining shields”. At one point in the battle, the barbarians apparently realized that the surrounded legion does not have enough strength to break out of the encirclement and instead of bleeding out in the fight against the bravely defending and probably better coping Roman legionaries, they abandoned the fight and proceeded to block the immobilized legion. They apparently decided to take advantage of the fact that the legion was immobilized by them in an open flat area without access to water. In addition, the extremely hot day when the legionaries had to fight, gave the Quadi legitimate hope that exhausted by the fight and the heat pouring from the sky, their wounds and the inability to quench their thirst by humans and animals – the Roman army would have to either give up and go into slavery, or if she does not want to give up, then due to exhaustion and low morale, sooner or later it will be destroyed by, for example, storming her position. In each of these situations, the Quads would have achieved a military victory over the Romans, and if the Romans had surrendered, they would have humiliated the Empire by capturing Roman troops sent against them. For now, however, the struggle continued. It is very possible that the Romans took advantage of the break-in the battle to take refuge in the hastily prepared fortified marching camp, i.e. the kind of camp they used to put up at the end of each day’s march (Latin castrum aestiva)11. Although the above sources do not mention it directly, this can be deduced from the fragment saying that the barbarians “put the guards everywhere and surrounded them so that they could not get water anywhere” while the Romans “stood sun-scorched on the battle line and in several posts”. In addition, since the legionaries could not break through the lap and a blockade was established around them by a larger opponent, sheltering the army behind a dug ditch and an erected embankment would be the most logical consequence of the situation. The immobilized legion would eventually find dusk sooner or later, and all the soldiers could not stand up all night and stand by. An unexpected night attack by the quad army could break down tired soldiers and lead to a rapid pogrom of the army. In contrast, the trenches and earth embankments that the Roman army always used to surround the campsite were part of a simple, but highly effective (despite a certain provisional) perimeter defence of its resting place at night12. Although not disturbed at the moment, the situation of the Roman army was still difficult due to the fact of the lack of access to water, which in the long run neither people nor animals could withstand. One of the ancient descriptions indicates that the barbarians most likely also took advantage of the break in the fight, leading preparations for the assault on Roman positions, in the case in which it would turn out that the Romans would not give up and would fight until the end. This is indicated both by the further course of the battle, but above all by the mention of Julius Kapitolinus saying that the Suebi had some kind of machine. Interestingly, the mention of Kapitolinus is the only ancient written source that indicates the use of siege machines by barbarians against the Romans. They were probably some kind of simple platform construction or siege towers, which, led to the periphery of the Roman camp, in the event of an assault on the Roman positions, would allow the transfer of Suebi warriors in several places at the same time for encamping this camp13. It does not seem that the barbarian army was carrying these war machines with them to the place of battle because in the summer of 173 the war was already underway in barbaricum. At that time, the Suebi on their own territory was de facto on the defensive, and they would not need siege engines – and for what purpose – conducting defence activities.

And here, when it seemed that the end of the Roman army was near and nothing could reverse the fate of the battle, suddenly it became overcast and rain began to pour from the sky. Cassius Dion reports that the legionaries immediately began to drink rain falling from the sky, turning their faces directly upwards. Water was also caught in everything that gave it the possibility of storing it, e.g. in raised shields, helmets and probably in all other vessels that were at hand. Having collected water, it was given to tired and thirsty animals so that they could drink too. The Suebi, realizing that heavy rain would refresh the forces of the surrounding Romans, wanting to prevent it, and also taking advantage of the confusion that inevitably had to sneak into the ranks of the thirsty and at the same time drinking Roman army began the attack. Some of the legionary drinkers resisted the attackers, but the confusion in the Roman ranks must have been quite large since Quadi almost failed to gain the position defended by the Romans. In this circumstance, Cassius Dion not without reason notices that “most of them [i.e. legionaries – note author]was so busy drinking that an enemy attack could cause great damage. “So, when the defeat seemed to be close again, and the barbarians break the Roman defence, an extraordinary event has once again occurred. Here, because the unleashed storm began to be accompanied by lightning, and in addition,, hail began to fall on the heads of the fighters. What’s more, the lightning striking, again and again, hit the charging Suebi killing and wounding, as we can imagine, some part of the Suebi warriors crammed in places where they tried to break the Roman defence. Lightning also destroyed at least one of the siege machines used by the Suebi. On flat, exposed terrain, the siege towers built by Suebi warriors were probably the highest of the points protruding above the terrain and thus were the most exposed to lightning. In this situation, the attack on Roman positions collapsed, and the Swabian army was demoralized by the losses suffered, and probably also by the fact that the forces of nature favoured its opponents – it fell into disarray. The lost battle would seem to have ended for the Romans not only (as ancient writers believe) by a miraculous rescue, but also a complete victory.

When presenting the “battle of the miraculous rain,” one cannot ignore the issue of interpretation of this event in ancient accounts, if only because they formed the basis of how it is determined today. It is quite obvious that the use of the concept of a “miracle” by modern historians (the first works using this term originated in the nineteenth century) in relation to an event that was a mere battle (although, of course, with changing happiness for both parties involved) – was a direct result of the ancient authors’ explanation of this event14. However, among the reasons for this “miracle” given by ancient histories, there are several interpretative variants to explain it. The ancient sources cited above represent three main interpretative variants of the miraculous ending of the described battle, and they are in conflict with each other15. One such variant is an attempt to attribute a wonderful end to the battle of the causative power of Emperor Marcus Aurelius himself. In this direction, a brief mention goes to Julius Capitoline, who in the passage quoted above (through the use of the words “won his requests”) recognizes “the miracle of rain and the lightning miracle” as a work of the will and power of Marcus Aurelius16. Another attempt to explain the “battle of the miraculous rain” is to look at its extraordinary course in a pagan religion (Latin interpretatio pagana)17. For example, Cassius Dion is a representative of the pagan tradition. According to Cassius Dion, the wonderful rain was prayed by the Egyptian magician Arnufis19(the most historical figure) who was in Roman ranks and in his prayers addressed various gods, in particular Hermes Aerios, whose Roman counterpart Mercury. And finally, another way to explain this event is to try to explain it based on the evolving Christian religion (Latin interpretatio christiana). This tradition is represented, for example, by the above-quoted account of Bishop Eusebius of Caesarea, who attributes the praying of a miraculous rain to legionaries who are Christians and who served in the XII legion of Melitene. For clarification, it should be noted that at that time the presence of Christian soldiers in the legion, which was stationed first in Syria and then in Melintene, Cappadocia, was most likely19.

Ending the account of the “miracle of rain and lightning miracle” it is worth emphasizing that the above-mentioned Eusebius of Caesarea indicates in his account one more interesting circumstance related to the battle. He states, in relation to the participating in the victorious battle of the XII legion with Melitene, that “the legion, which through its prayer caused this miracle, received from the emperor in remembrance of that event the significant Latin name of the legion thunderer”. He uses the Greek word keraunobolos, whose Latin equivalent is fulminatrix, which can be translated for this legion as “thunderbolt”20. The above mention, however, is considered a mistake of this historian, because the name of the Legion XII of Melitene was already confirmed in sources and since the time of Octavian Augustus she had the Latin nickname fulminata, whose Greek equivalent is the word keraunoforoswhich can be translated as “carrying lightning”. This nickname was supposed to come from the individual sign of this legion, which was the image of lightning21. Therefore, since Eusebius of Caesarea was mistaken and twisted the nickname of the Melitean legion from Fulminatto Fulminatrix, mistakenly believing that it was given to this legion only in memory of his participation in the “battle of miraculous rain” – Is it not unusual in the whole story that participation in the “miracle of rain and miracle of lightning” fell to the legion whose sign and the nickname was anyway … lightning.

Marcus Aurelius gracious and triumphant

Shortly after his victory, the king of usurper Ariagaesus was captured. The victorious battle and the capture of the king of Quadi had the effect that soon the Suebi asked for peace. The room conditions were harsh. Quadi was ordered to release all Roman prisoners and was forbidden to settle within ten miles of the Roman border on the Danube (i.e. about 15 km). They were also forbidden to enter the Roman markets located in the adjacent zone, which was an economic sanction striking one of the foundations of the existence of the Suebi tribes, i.e. trade with the Romans. In addition, the Quadi were obliged to provide their own recruits to the Roman army. The latter were immediately incorporated into various Roman units (the so-called numerii)22. And what happened to the Quadi’s king-usurper, for whom the emperor appointed a prize and whose usurpation led to the resumption of war with Quadi? The answer to this question is given to us by Cassius Dion, who in his work presented the fate of the former King of Quadi – Ariagaesus: “Marcus was so fierce at Ariagaesus that he issued a proclamation proclaiming that whoever would bring him alive will receive a thousand pieces of gold, and that, who will kill him and show his head – five hundred. However, in other cases, the emperor used to treat even his most vicious enemies humanly: for example, he did not kill, but only sent Tiridates, a satrap, to Britain, which caused a riot in Armenia (…). So this shows how great his anger at Ariagaesus was. However, when this man was later captured, he did not hurt him but sent him to Alexandria”23. Thus, although Ariagaesus was banished to Alexandria in Egypt, he kept his head, and his pardon by the emperor should be considered an extraordinary circumstance at a time when captured enemies of Rome graced the triumphal parade of the victorious leader so that after his end he would usually be ritually strangled24.

However, it was too early for the triumphal march. After making peace with the Quadi, in the same year 173, the Romans began the war with the Yazygs. They decided to retaliate for the participation of this Sarmatian tribe in the invasions of Roman territory. Starting the war against the Yazygs, the emperor also wanted to weaken them permanently, because so far they have not suffered more severe losses in the fighting and thus were a constant spark of the revolts of the remaining, seemingly subdued, Germanic tribes. On the other hand, the Quadi, despite losing in the “battle of miraculous rain” and peace, they still did not give up anti-Roman policy. Initially, they unofficially supported their Sarmatian allies (Iazyges) fighting the Empire. “The battle on the frozen Danube”) broke the peace of 173 and again began regular military action against the Romans. In April 175 exhausted by fighting, they again turned to peace. The emperor agreed to peace, thus weakening the Iazyges, whom they assisted they were militarily (Fig. 2). The conditions of the new peace with the Quadi were relaxed compared to the peace conditions of 173. For example, they were banned from settling in the border zone from the previous ten miles from the Roman border (i.e. about 15 km) to five miles from the Roman border (i.e. about 7.5 km). Thus, the Iazyges remained alone in enter the fight. Soon, in June 175, the exhausted and lonely Iazyges also asked for peace. Initially, the emperor refused to make peace to the Yazgi, intending to wage war until their complete destruction, but these plans were thwarted by the rebellion in Syria. Most likely due to the false news of the emperor’s death in 175, Gaius Avidius Cassius, the commander of the Eastern legions and the superior of the whole East proclaimed himself the emperor. The Senate declared him an enemy of Rome, and the righteous emperor Marcus Aurelius was forced to go against the usurper. Unwillingly, the emperor interrupted his hostilities against the Yazygs to avoid war on two fronts. In this way, peace reigned in the northern parts of the Empire in 175. After suppressing the revolt of Avidius Cassius in the East, the emperor inspected the eastern borders of the empire and returned to Rome at the end of the following year25. The victories won by the emperor over the Germans and Sarmatians in the course of prolonged fighting were finally crowned with a solemn triumph, which the emperor (and his son Commodus) made on December 23, 176.26

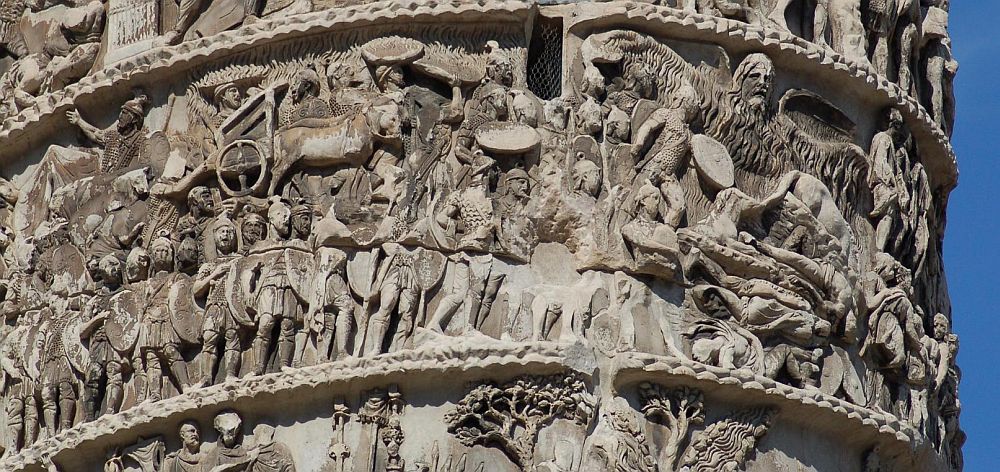

Most likely, also at that time – i.e. in 176 – a relief decoration was designed to commemorate the events of the Marcomannic Wars, which was then carved on a specially built column. It should be clarified that this column, although it was completed by 193, and therefore after the death of Emperor Marcus Aurelius (the emperor died in 180), it is due to the fact that its relief decoration curling in the form of a ribbon on the column stem, it shows almost exclusively the Roman counteroffensive from 171-175 (without 177-180) allows to conclude that the whole had to be designed shortly after the conclusion of the said room in 175. The column of Marcus Aurelius (because it is also so-called nowadays) is the basic iconographic source about the Makoman Wars27. Interestingly, the “miracle of rain and lightning miracle” was among the events depicted on the stem of the column in the form of two separate scenes. Scene No. XVI presents the “miracle of rain”. Scene No. XI – “lightning miracle”. With the ribbon wrapping around the core of the column, the “lightning miracle” scene (number XI) precedes the scene showing the “miracle of rain” (number XVI). This gave rise to historians’ ongoing and unresolved disputes since the nineteenth century, whether both events should be combined with each other as occurring during one battle, or whether they are separate, unrelated battles, accompanied by supernatural events28. The expression of this distinction and ongoing disputes of modern historians is somewhat the cited above concept of “the battle of miraculous rain”, limiting the supernatural events accompanying the ancient battle only to the “miracle of rain”. Either way, in scene XVI referring to the “miracle of rain” one can see, among others a legionary figure with his arms raised and looking up at the sky. It looks as if the legionary was either begging for the help of the gods, or he was thanking the gods for the miracle in the form of rain falling on him. Above the legionary, there are neither arms nor wings of a semi-human bearded figure floating in the air. Streams of water flow from the long beard and wings of arms (or maybe shoulders) of this menacing-looking character. With this water, Roman soldiers and animals quench their thirst. It is also seen that some legionaries catch rain falling on inverted shields (see Photo 1).

Author: Cristiano64. Title photo: Il miracolo della pioggia sulla Colonna di Marco Aurelio (Polish: Miracle of rain on the column of Marcus Aurelius). Fig. licensed under CC BY-SA (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/). Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Miracolo_della_Pioggia.JPG.

This scene also shows a pile of bodies of killed barbarians and their horses. The bodies of the dead pile up below the mysterious figure looking at them from above, which is supposed to suggest that it was she who contributed to their destruction (see Photo 1 and Photo 2). It is assumed that this bearded figure is the highest of the gods of the Roman pantheon, that is, Jupiter with the nickname Pluvius(Latin “sending rain”). The “battle of the miraculous rain” presented in the manner described above on the Column of Marcus Aurelius is maintained in the current interpretatio pagana, although in a slightly different version than the version presented by Cassius Dion. It is in vain to find a bas-relief of the emperor and Egyptian magician Arnufis, whom Cassius Dion mentioned in his account, which in turn contributes to the current scientific considerations whether the emperor personally participated in this battle29.

Author photo: Barosaurus Lentus. Title photo Detail from the Column of Marcus Aurelius in Rome (Detail from the column of Marcus Aurelius in Rome). Fig. under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/). Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Column_of_Marcus_Aurelius_-_detail2.jpg.

In turn, in scene XI presenting the “lightning miracle” you can see Roman legionaries locked in a fort besieged by barbarians. The fort is besieged by siege engines. One of them is broken and burning, and smoke coming out of it rises to the sky. Around the burning siege machine,, you can see killed Suebi warriors. From the smoke rising up towards the sky another lightning emerges, which in a moment will strike against the Swedish army again (see Photo 3). Scene XI on the Column of Marcus Aurelius is, therefore, the second ancient source (of course iconographic) which, next to the written mention of Capitoline, indicates that during the battle the barbarians used siege machines against the Romans – most likely siege towers. It is a source which, being the closest to the presented events, may even be regarded as primary in relation to the above-mentioned written mention of Julius Kapitolinus, which, due to the time of the creation of the work in which it was found (turn of the third and fourth century), maybe a secondary source30. On the other hand, the use of siege towers, documented by the Germans against the Roman army caught by them in traps, clearly shows that since the wars led by the emperor Octavian Augustus in Germania from the beginning of the first century, the barbarians learned a lot in the field of war art. It was not a good omen for the Empire for the future31.

Author: Helen Simonsson. Title photo: The Column of Marcus Aurelius, CE 180-192, Rome (Polish: Column of Marcus Aurelius, 180-192 CE, Rome). Fig. licensed under CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/). Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/hesim/6306369810/in/album-72157648227403581/.

The peace of 175 did not, however, end the Marxian wars. After two years of fragile peace, in 177, fighting over the Danube broke out with new strength. The Quadi (but also the Marcomanni and Sarmatian Iazyges) broke up again to fight against the Empire. At one point, the emperor even considered the creation of two new provinces of the empire in pacified barbarian areas – “Marcomannia” on Marcomannii-Quadi trains and “Sarmatia” in the area inhabited by Sarmatian Iazyges. There are several reasons for this. Marcomanni and Quadi after a dozen years of conflict were already very exhausted and basically completely pacified. Their territory was occupied by about 20 thousand. Roman soldiers deployed in a dense network of fortified camps covering them. They were also not chosen (i.e. Marcomanniom and Quadi) clientele rulers. It is worth mentioning here that the creation of new provinces to approximately cover the areas of today’s Austria, the Czech Republic and Slovakia would not only romanise these new areas but would also have the effect that Roman science and culture would directly affect Germanic tribes inhabiting the areas adjacent to this new province, that is to the central part of the then barbaricum. Perhaps it would radiate even further north to the Vistula and Odra river basins, which could permanently (in a positive way) change the history of this part of today’s Central and Eastern Europe32. Anyway, the implementation of these possible plans was hindered by the death of the emperor, which took place on March 17, 180 in the Vindobon Danube military camp (today’s Vienna, Fig. 2). Son and successor of Marcus Aurelius on the imperial throne – Commodus – after a short campaign, six months after the death of his father, he made peace with both Germanic tribes. The room imposed certain restrictions on the barbarians (according to some historians, they were not very strict in relation to the condition they were in at the time). However, the peace treaty also provided for the withdrawal of the Roman army from its barbaric territory. The northern border of the Empire remained unchanged33. So, if Marcus Aurelius actually planned to create two new provinces that would shift the borders of the Empire further north, leaning them against the arch of the Carpathians, these plans with his death were irretrievably lost, and the history of Central and Eastern Europe took a course known to us.