The origins of the Jewish people have been a topic of discussion throughout history, characterized by complexity and sometimes bias. In today’s era, armed with numerous historical sources, we can more accurately trace their ethnic roots. However, in the early days, especially during the classical period, historians grappled with the challenge of unraveling this enigma. Tacitus, a prominent historical figure, delves into this question in his significant work The Histories, Book V, composed around 110 CE. In this narrative, Tacitus explores various theories and possible interpretations of Jewish origins, including some less emphasized ones that offer intriguing classical perspectives. While the final explanation provided by Tacitus is often cited, these lesser-known interpretations provide a nuanced and complex view of classical thought on the Jewish exodus, adding an interesting layer to a forgotten past.

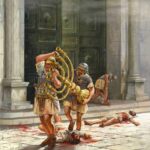

In his book The Histories, Book V, written c. 110 CE, Tacitus gives his rendition of the history of the Jewish people. Tacitus’s rendition of history has been proven to be a mix of facts, fiction, and anti-Semitic rhetoric. Preceding his discourse on the 70 CE collapse of the Second Temple, Tacitus unfolds his interpretation of the Jewish origin. Striving for impartiality, he engages in thorough analysis, presenting diverse arguments for the genesis of the Jews before ultimately crystallizing his definitive assertion in (5:2):

Plurimi auctores consentiunt orta per Aegyptum tabe quae corpora foedaret, regem Bocchorim adito Hammonis oraculo remedium petentem purgare regnum et idgenus hominum ut invisum deis alias in terras avehere iussum. (Tacitus 5:2)

This assertion posits that the prevailing notion attributes the migration to a sweeping epidemic in Egypt, prompting the ‘race of men as hateful to the gods,’ namely the afflicted, to seek refuge in distant lands, ultimately leading them to Judea. Expanding on this foundation, he explores his argument, offering various criticisms against the Jewish people. Subsequently, he delves deeper into the intricacies of their characteristics. However, Tacitus, prioritizing this viewpoint in his writing, has led to neglect of other verses about the origin of the Jewish people, though these verses carry a certain fascination. One such theory proposed by Tacitus concerns the exodus of the Jewish people from the island of Crete.

Iudaeos Creta insula profugos novissima Libyae insedisse memorant, qua tempestate Saturnus vi Iovis pulsus cesserit regnis. (Tacitus 5:1)

The direct translation could be roughly interpreted as some experts arguing that Jews were fugitives from Crete. According to this interpretation, they arrived on the nearest coast of Africa when Jupiter displaced Saturn from his throne using his power. Tacitus supports this perspective with the following pieces:

Argumentum e nomine petitur: inclutum in Creta Idam montem, accolas Idaeos aucto in barbarum cognomento Iudaeos vocitari. (Tacitus 5:1)

The root of the argument stems from the mountain “Ida,” and the neighboring tribe, the Idaei, whose name eventually morphed to become “Judaei.” However, almost all classical sources go against this generalization. Contrary to what Tacitus suggests, the mountain seemingly got its name from the term Ἵδη (Ida), mentioned in Iliad (Iliad, 2.821), which translates to a “wooded hill.” This, in turn, was related to the Minoan mother goddess religion. Thus, the people who lived in the vicinity, the Idaeil, also most likely got their name from the mountain and do not correlate with the Jewish people at all. Reinach posits that this perspective, while intriguing, should be contextualized within the Cretan origins of the Philistines. However, the linkage between the Jews and Saturn, drawn from mythological references, yields scant historical information. Classical evidence does attest to a Jewish presence on Crete, as elucidated by Josephus Flavius in his comprehensive works (Vita, 427), recounting how he “married a wife who had lived at Crete, but a Jewess by birth.” While there is historical documentation of Jews dwelling in Crete during antiquity, it fails to substantiate Tacitus’s imaginative correlation between the mountain and the Idaeil tribe. Tacitus, nonetheless, advances an alternative perspective on the potential origin of the Jews:

Quidam regnante Iside exundantem per Aegyptum multitudinem ducibus Hierosolymo ac Iuda proximas in terras exoneratam. (Tacitus 5:1)

A rudimentary interpretation of the passage suggests that some believe that the reign of Isis, Hierosolymus, and Judas led an overflowing population from Egypt into neighboring countries. This perspective posits Jews as a colonial force originating from Egypt, an uncommon view lacking substantial evidence, notably highlighted by Diodorus Siculus’s Library of History.

The argument presented contends that Egyptians claim their ancestors dispatched numerous colonies globally, attributing it to the pre-eminence of former kings and a substantial population. However, lacking precise proof, these claims fail to garner support from credible historians, leading to their exclusion from recorded accounts, as observed in Siculus’s rejection of such assertions. Applying a comparable standard, it becomes evident that Tacitus’s hypothesis on the Jewish colonial exodus from Egypt lacks substantiating evidence. Tacitus’s third perspective introduces the notion of Jews being of Ethiopian origin, expelled by their neighbors to seek new lands during the reign of King Cepheus, as indicated by the following quote:

plerique Aethiopum prolem, quos rege Cepheo metus atque odium mutare sedis perpulerit (Tacitus 5:1)

The mention of King Cepheus noticeably shifts the narrative towards the myth of Andromeda, prompting a persistent debate regarding whether the myth unfolded in Jaffa or Ethiopia. This debate appears to find its roots in the mention of King Cepheus. While Jaffa is a seemingly preferable location, supported by a 5th-century B.C. fragment from a comedy by Cratinus linking Syria and Perseus, Tacitus, in this context, likely refers to Ethiopia as a means of bridging the initial and the third arguments. Consequently, the third argument can be dismissed, given the lack of validity in the first proposition. Consequently, the assertion of Jewish origin from Ethiopia lacks a discernible basis.

Sunt qui tradant Assyrios convenas, indigum agrorum populum, parte Aegypti potitos, mox proprias urbis Hebraeas- que terras et propiora Syriae coluisse. (Tacitus 5:1)

Tacitus’s second to last argument is more in line with biblical accounts than any of the other of his proposed arguments. This suggests that a diverse group of landless Assyrians took residence in a portion of Egypt, subsequently establishing their cities. They settled in the territories belonging to the Hebrews and the adjacent regions of Syria. The Assyrian heritage was a large popular claim, upheld most notably by Nicolaus of Damascus and Pompeeius Trogus. The trek to Egypt and the return to Hebrew lands is also largely by the bible. This is the most probable of all of the suggestions that Tacitus has put forward so far. Extensive proof shows a Jewish history stemming from Mesopotamia, and various DNA tests have not excluded that potential possibility. All in all, there is not enough data to accurately conclude to what extent Tacitus was right, if there is any truth to this claim at all. The last of Tacitus’s theories proposes Jews as the Solymi—a nation renowned in the poems of Homer. According to this account, they founded a city named Hierosolyma, derived from their name.

Clara alii Iudaeorum initia, Solymos, carminibus Homeri celebratam gentem, conditae urbi Hierosolyma nomen e suo fecisse. (Tacitus 5:1)

While the concept positing the Jewish identification with the Solymi may bear literary or mythological significance, its lack of empirical verification necessitates a cautious assessment. E.J. Bickerman, a prominent scholar in Greco-Roman history and the Hellenistic world, contends that this identification likely does not stem from a Jewish source. Josephus Flavius, who used the term Solymi in his work Contra Apionem, is mentioned in footnotes, pointing out a clear difference between the Jews and the Solymi. This suggests that the term might refer to the Solymi of Pisidia rather than the Jews in Judea. Without supporting evidence, the credibility of this claim is questionable. While scholars generally agree with a well-established historical narrative about the Jewish exodus and its origin, it’s still essential to explore unsuccessful accounts. These less successful perspectives provide an alternative yet instructive angle in historical discourse.