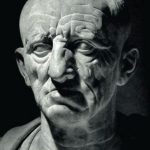

In ancient times, the Romans originally did not have great respect for doctors. Their knowledge and possible remedies came from rural life. Treated with simple home remedies. Cato the Elder writes that the father of the family – pater familias should have the appropriate knowledge.

This is how Plutarch shows his approach to medicine :

He himself, he said, had written a book of recipes, which he followed in the treatment and regimen of any who were sick in his family. He never required his patients to fast, but fed them on greens, on bits of duck, pigeon, or hare. Such a diet, he said, was light and good for sick people, except that it often causes dreams. By following such treatment and regimen he said he had good health himself, and kept his family in good health.

– Plutarch of Caesarea, Cato the Elder, 23

The first doctors were often Greek slaves (servi medici). It was not proper for a Roman to pursue this profession. There were also plenty of charlatans, ignorant quacks and magicians.

In the 2nd century BCE the success of Archagatos’ wound surgeon paved the way for other doctors, but due to his actions, which were associated with severe pain in patients, he was nicknamed Carnifex, meaning “executioner”.

Roman society was highly distrustful of foreign doctors. Cato the Elder presented his opinion on the Greek doctors. In his letter to his son, he writes:

In due course, my son Marcus, I shall explain what I found out in Athens about these Greeks, and demonstrate what advantage there may be in looking into their writings (while not taking them too seriously). They are a worthless and unruly tribe. Take this as a prophecy: when those folk give us their writings they will corrupt everything. All the more if they send their doctors here. They have sworn to kill all barbarians with medicine—and they charge a fee for doing it, in order to be trusted and to work more easily. They call us barbarians, too, of course, and Opici, a dirtier name than the rest. I have forbidden you to deal with doctors.

– Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 29.13-14

Many Romans used the services of suspicious medics offering mysterious ointments, elixirs or praying to the gods. Over time, in the Roman state, a kind of competition arose between doctors who, wanting to gain fame, prescribed various types of medicines and recommendations for the sick, which often ended in death for him. An interesting fragment was left by Pliny the Elder.

(…) man who swept away all the precepts of his predecessors, and declaimed with a sort of frenzy against the physicians of every age; but with what discretion and in what spirit, we may abundantly conclude from a single trait presented by his character — upon his tomb, which is still to be seen on the Appian Way, he had his name inscribed as the “Iatronices” — the “Conqueror of the Physicians”. (…)

Hence those woeful discussions, those consultations at the bedside of the patient, where no one thinks fit to be of the same opinion as another, lest he may have the appearance of being subordinate to another; hence, too, that ominous inscription to be read upon a tomb, “It was the multitude of physicians that killed me.– Pliny the Elder, Natural History XXIX, 5