Chapters

Ludus latrunculorum (also called latrunculi or latrones or milites) was a Roman board game that was extremely popular. Most likely, two players took part in the game.

The term latrunculi literally means “rogues” or “robbers”; therefore, the game can be called rogue/robber game. The game was seen as a tactical clash of two armies, as evidenced by Latin military terms often used in sources. The earliest Roman source – Varro (116-27 BCE) – indicates that the game was played on a board that was divided by intersecting lines. Players’ pieces, in turn, moved around the fields between them. In the poem Laus Pisonis of unknown authorship we learn, in turn, that latrunculi enjoyed great popularity in society, as evidenced by the large audience in the clash in which the glorified Senator Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso took part. We also know that players had different pawn colours, e.g. white and black. Ancient authors also used different terms for game pieces: miles, latro or bellator – however, according to scientists, this may be due to the desire to avoid repetition. In Europe, archaeologists have found countless game pieces – made of glass, ceramics, bones and other materials.

To this day, however, no more detailed antique descriptions of the game have survived. Information about the game can be found in the mentioned Varro or Martialis, Ovid or Macrobius; the last mention is from the 4th century CE. The Roman game was a variation of an earlier Greek game called petteia (other names: pessoí, psêphoi, poleis or pente grammaí). Latrunculi did not survive the fall of Rome, but a similar game was still present in Persia in the 10th and 11th centuries. According to specialists, the gameplay resembled modern chess or checkers.

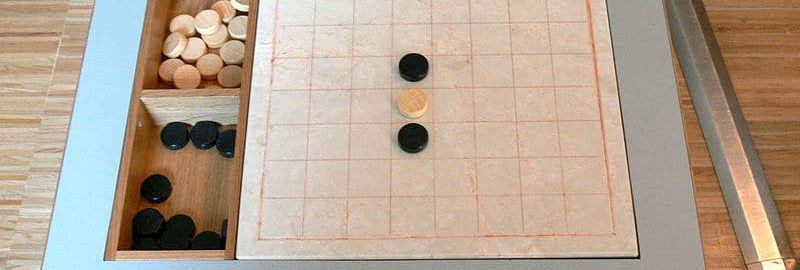

However, thanks to archaeological discoveries, we are able to slightly recreate the appearance of the game board. Boards with dimensions of 7×7, 7×7, 7×8, 7×10, 8×5, 8×8 or 9×10 have been discovered in Britain. In other regions of Europe, 9×9 boards were found. This proves that the appearance of the latrunculi board was not fixed.

Players set the number of pieces. For boards 8×8 and 8×9, 16 to 24 pieces were used; for 7×7 or 7×8 boards from 14 to 21 pieces were used. At the beginning, each player set the pieces (called vagi by Isidore of Seville) on the board in free spaces – at this time there was no beating1. Then came the right game. Players decided among themselves which one to start first. Pawns (at that time called ordinarii by Isidore of Seville) could be moved in any direction (horizontally or vertically) by any number of boxes2, but they could not be moved above the pawns or land on them. Beating took place by capturing (i.e. adding your pawn to the opponent’s pawn in such a way that on the other side of the enemy pawn stood another own pawn). Seneca the Younger proves, however, that immobilizing the pawn did not mean immediately removing him from the board – related to this were more complicated game rules, such as loss of turn. Played until all pieces were captured.

Many people have tried or are currently trying to reconstruct the rules of the game, including Ulrich Schädler (2001), RC Bell (1960-1969) and Edward Falkener (1892). Roman gameplay suggestions differ then in terms of rules, number of fields and pieces.

Let’s play latrunculia!

It really doesn’t take much to try this ancient game yourself. According to the Ulrich Schädler version, a board with 8×8 fields should be prepared. We need to set the number of pieces that will participate in the skirmish: from 16 to 24 for each player. Of course, we can increase the board, but then the number of pieces must be increased. Of course, player pieces must also be different. Game rules:

- Each player spreads, alternately, their own pieces on empty fields of the board. According to Izydor from Seville, such pieces were referred to as vagi. At this stage, naturally, there is no “catching” of enemy pawns.

- When all the pieces are on the board, players choose the person who will start first. The game starts and players move their pieces (now referred to as ordinarii) one by one horizontally or vertically. A player’s pawn may jump over any adjacent pawn, provided that the next space is empty. There is no limit to such moves.

- If your own pawn was between two opponent’s pieces, then it is blocked and referred to as alligatus (or according to Isidore incitus).

- In the next turn, the blocked pawn is removed from the board and no longer takes part in the game. A blocked pawn can move when one of the blocking enemy pawns is also blocked.

- A player may move his pawn between enemy pawns only if one of them is blocked.

- A player who has only one piece on the board loses.