Chapters

Tents were in use already in ancient times. The ancient Romans used them mainly in marching camps (castra aestiva), which were pitched during military campaigns every day. We owe much information about their construction to the excavations at Vindolanda or Newstead, where leather materials have been preserved. Information about the use of tents by the Romans in war is also provided by reliefs from Trajan’s column in Rome, where selected moments of the Dacian War are depicted.

Tents are primarily associated with the contubernium – the smallest organised unit in the Roman army, which consisted of eight legionaries. The soldiers of such a unit were called contubernales. In reality, there were two additional people in the unit – servants or slaves who did the packing or cooking. Officially, they were not included in the unit. It is worth mentioning that the soldiers taking part in the campaign were called sub pellibus (“under the skin”), because of the leather tents in which they slept. Each contubernium had its own tent, which was about 3 m wide and 1.5 m high. The tent was transported by a mule, assigned to the troop. The animal carried on its crest: two tent poles, a folded leather tent, pegs, ropes, two baskets (used for digging the camp ditch), digging tools, a small stone mill for grinding grain and extra food. As mentioned the tent could accommodate up to 10 people and clothes or more useful items that needed to be protected from the rain. Other items and weapons were located behind the tent. The tents of the contubernia were numerous and therefore certainly adjoined each other in the camp. The tents belonging to the century were in one row, and at the end was the centurion’s tent of relatively similar dimensions (Cornelius, 2012).

Artefact description

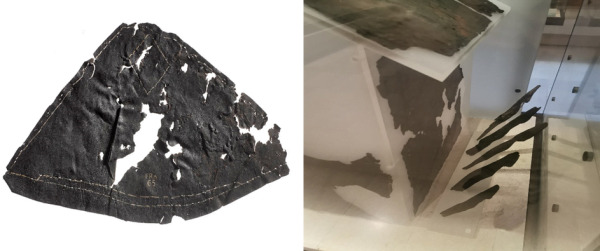

The Roman army tent found in Newstead has been dated to 80 – 180 CE (NMS). The find consists of thin fragments of skins (Figure 1) and tent pegs (Figure 3), which when assembled give an outline of the tent’s appearance. A closer look at the individual irregular pieces of leather reveals traces of sewing where the pieces were joined together, as seen at the cone-shaped top of the tent (Figure 2). The tent pegs were carved in such a way as to make it easier to drive them into the ground, and they ended with hooks that prevented the tent ropes from slipping. This finding is remarkable considering that organic materials such as leather and wood preserve poorly in the deposition material, being prone to rapid decomposition, where much of it has deteriorated over the centuries, including the rigging.

Roman impact in Scotland

The Newstead find demonstrates widespread military activity within Scottish territory. The finding of the tent indicates that the Romans employed the same tactics used elsewhere in Europe. Mobile troops arriving at favourable positions were originally stationed in such constructions, which were later replaced by more durable structures made of wood and stone. By examining the location of the pegs during the excavations, the researchers were able to determine the size of the encampment, which consisted of twenty tents, standing in two rows of ten along a constructed road (Curle, 2004: 66). The presence of this tent at Newstead is evidence of the continuity of military tradition and the discipline of the army even in such remote lands as Scotland and testifies to the mobility of an army ready to face adverse weather conditions.

The exhibition

The Newstead tent forms part of a larger museum exhibition on ancient Romans. The area of the museum where the exhibition is located (Figure 4) forms the story of the Roman invasion of Scotland, where we can learn about the warfare techniques used by the invaders, their daily life or trade with other peoples, shown in the artefacts they left behind. In the adjacent showcases, we can see elements of the equipment of Roman soldiers, armour, helmets, weapons, footwear or horse accessories. Inside the showcase that contains the tent (Figure 1) is a scaled-down reconstruction of the size and shape of the tent, on which stretches of tent skin were overlaid. Next to the tent are the pegs in the position they could have been used when setting up the camp (Figure 3). The exhibition is accompanied by a short description placed at head height behind the tent, and a time scale with the dating of the find. The exhibition is easily accessible and clear to visitors, although the dilapidated tent itself does not attract as much attention being surrounded by magnificent items made of colourful metals.

Conclusion

The Newstead tent, despite its age, has survived in good enough condition to allow its identification and reconstruction. It is an inseparable, strategic element of a soldier’s equipment giving him the possibility of survival in unfavourable conditions in distant lands during numerous military campaigns conducted by the Roman Empire. Its presence on the archaeological site allowed us to estimate the size and the number of troops of the garrison and proves the continuity of the military tradition. Today, preserved and restored, it forms part of the National Museum of Scotland’s exhibition on the Roman presence on Scottish soil.