Chapters

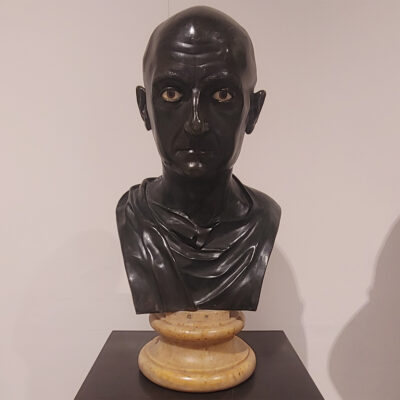

African Scipio the Elder was born in 236 BCE in Rome as Publius Cornelius Scipio (Publius Cornelius Scipio). Publius came from the old patrician family of Cornelius, more specifically from their line nicknamed Scipio. He went down in history as a brilliant commander and defender of Rome against Hannibal.

He was the elder son of Publius Cornelius Scipio, a former praetor and consul for 218 BCE, and Pomponia, who came from a plebeian family. His younger brother was Lucius Cornelius Scipio Asiaticus.

Military and political career

As he came from a good and significant family, he had a good education and career prospects in Rome. His favourite reading was the descriptions of the campaigns of Alexander the Great, whom he admired and wanted to imitate. He spent the entire period until his adolescence studying Latin, Greek and the art of oratory. In addition, like any young man of his condition, he had to explore the secrets of military art, which he liked the most.

In his youth, Scipio used to go alone to the temple of Jupiter in the Capitol, where he sat alone, devoting himself to meditation. He later openly stated that his actions were sometimes guided by dreams sent by the gods.

When the Second Punic War broke out in 218 BCE, Scipio, like many other sons from good families, accompanied his father who was elected consul for this year. Such practice was considered a good way of gaining military experience by young aristocrats and a significant step in their political careers.

Despite being only 18 years old, he took part in the battle on the Ticinus River, where he was supposed to save his father from death, and on the Trebia in 218 BCE Scipio the Younger gained valuable experience despite two defeats by the Roman army and in 216 BCE, at the age of 20 he was appointed as a military tribune in the Second Legion, one of eight such units jointly commanded by the consuls Lucius Emilius Paulus and Gaius Terentius Varro. Scipio received the position due to family connections because he was married to Paulus’ daughter, Emilia.

On August 2, 216 BCE, Scipio took part in the great battle of Cannae. There, Hannibal’s army encircled and almost annihilated the overwhelming power of the republic. The number of victims was enormous, especially among senatorial families, and consul Paulus himself was left on the battlefield. Scipio was one of the four stands to be among the survivors in the nearby town of Canusium.

As few tribunes were left alive, the command fell to Scipio and Appius Claudius. The scale of the defeat was so great that one group of survivors of the slaughter led by Quintus Cecilius Metellus began to think about desertion and fleeing the country. It was only under the influence of Scipio’s vigorous and honourable behavior that they changed their minds and came under his command.

Gradually, nearly 10,000 survivors from the battle gathered in one place and put themselves at the disposal of Scipio.

After conquering Carthago Nova, Scipio received a beautiful girl as war booty. Upon learning that she was engaged, he returned her, intact, to his parents with generous gifts for his fiancé.

From 216 to 213 BCE, it is not very clear what happened to Scipio’s political career. It is possible that he still served in the army and collected volunteers for the war. In 213 BCE it is known that he was elected to the post of curule aedile, and in 211 BCE his father and uncle died in Spain. Unable to reach an agreement on the appointment of a commander in the Iberian Peninsula, the Senate decided to settle the matter through elections and convened a comitia centuriata. At first, there was no one, until finally, unexpectedly, Scipio submitted his candidacy and was elected unanimously. In 210 BCE he made a speech and, having received the post of the proconsul, was sent to Spain.

Initiative of the Romans

The twenty-six-year-old commander landed in Emporion, a Greek colony in Spain, already allied with Rome before the war. He brought 10,000 reinforcements with him, which increased the strength of the Roman army in the province to 28,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry.

In Spain, during this period there were three Punic armies, which, however, operated at great distances from each other, which did not allow them to cooperate. So Scipio got a sense of his chance, but the fear of too long stalks and waiting for his rival prompted him to change his plans. He decided to attack Hannibal’s main base in Spain, New Carthage. He obtained it in 209 BCE using the knowledge of local fishermen. Knowing that the lagoon separating the city from the mainland is very shallow, he decided that some legionaries would enter from this side, completely surprising the enemy. The rest he ordered to simulate an attack on a heavily defended isthmus. The Romans quickly crossed the lagoon and climbed the walls. The Carthaginians did not expect an attack from this side and were completely taken by surprise. The 3,000th crew was almost to the leg. The loss of New Carthage with its port and nearby silver mines was a powerful blow to the Punics. After this victory, the Roman commander began extremely intensive training of his soldiers, turning them into real killing machines.

Having a well-trained army, Scipio in 208 BCE set off against Hasdrubal Barcaras, the younger brother of Hannibal. He defeated him at the Battle of Baecula and forced him to leave the Iberian Peninsula. When Hasdrubal regained his confidence and joined forces with Magnon Barkas, he set off against Scipio. In 206 BCE, the two armies met at the Battle of Ilipa, where 40,000 Romans faced nearly twice as many Hasdrubal’s army of 72,000 and 32 war elephants. Scipio noticed that the enemy’s wings were formed by weaker units of Gallic mercenaries, and there he directed the strikes of his best units. The Punics were completely smashed, and their losses amounted to 68,000 killed. The manoeuvre used by Scipio during the battle is called the “inverted Cannae”.

Scipio’s campaign, which resulted in Carthage losing control of Spain, was a turning point in the Second Punic War.

After an amazing campaign in Spain, Scipio decided to go to Numidia on a diplomatic mission. There he also tried to get Prince Syfax and Masynissa to his side. It ended with partial success because Masinissa was turned to the side of the Romans, hungry for vengeance on Syphax, whom Carthage supported against him in the competition for the throne.

Scipio’s brilliant successes earned him the post of consul in 205 BCE and the right to govern Sicily. In addition, the Senate agreed to his plans to attack the enemy homeland in North Africa.

In 204 BCE, 30,000 of the best Roman soldiers landed under the command of Scipio near Utica, north of Carthage. The troops trying to fight them off were destroyed. The Romans were soon joined by the Numidians of Masinissa, consisting of light cavalry. Successive Carthaginian troops blocked Scipio in his camp called Castra Cornelia. However, by pretending to be willing to make peace talks, he lulled the vigilance of his enemies. One night he launched a surprise attack on their positions. His men set fire to the tents of the Carthaginians. Almost all Punic soldiers died in the flames.

Meanwhile, Hasdrubal gathered a new army of 30,000, but in 203 BCE he suffered a terrible defeat at Bagrades. The Romans took over the area around Carthage. The terrified Punics agreed to peace on tough terms. However, when Hannibal arrived in Africa with the remnants of his army, peace was broken. The two great leaders clashed at Zama in 202 BCE, Scipio had about 35,000 men and Hannibal about 38,000. However, the Carthaginian army was mostly composed of inexperienced recruits, and the hundred young elephants were not properly trained. Thanks to this, the Roman forces finally won, forcing Carthage to accept the new terms of peace.

After returning from Africa, Scipio made a spectacular triumph and took the name Africanus, meaning African, in memory of his achievements. In 199 BCE he reached the highest level in the Roman magistrate, the office of censor.

In 194 BCE, when he became consul for the second time, he led an army against the Gallic tribes in northern Italy, without engaging in heavy fighting.

In 190 BCE the conqueror of Carthage, at the request of the Senate, headed an expedition against the Seleukid king Antiochus III, receiving a consulate with his brother Lucius. He directed the crossing to Asia Minor and developed a campaign strategy. Shortly before the decisive battle of Magnesia in 190 BCE, Scipio fell seriously ill and had to hand over the command to his younger brother Lucius Scipio. He shattered Seleucid’s army despite her overwhelming superiority in numbers, largely due to advice given to him by his older brother, who was serving as the most senior subordinate, legatus.

Forgetfulness and death

After returning from the war in 188 BCE, both brothers became the heroes of a scandal. They were accused of embezzlement of state funds during the campaign. Scipio’s incompetent political appearance during the trial in 187 BCE and the scandal caused by the attitude of the senate led to his withdrawal from public and political life. The chief left Rome, going to his estate in Liternum, on the coast of Campania, near Naples. Formerly adored, now abandoned, he lived there for the rest of his life.

He died forgotten in 183 BCE.

Marriages and children |

|