Chapters

Battle of Agrigentum (261 BCE) was a victorious clash of Roman troops over Carthage in the First Punic War. If Polybius is to be believed, the victory prompted the republic on the Tiber to completely remove the enemy from Sicily.

Historical background

First Punic War is associated with battles fought by fleets in the Mediterranean, the debut of Rome’s warships or a famous Roman invention – a crow thrown on board enemy ships. Relatively little attention is paid to another aspect of the conflict – the struggles on land, especially the first historically certified use of war elephants by Carthage.

The reasons for the outbreak of the First Punic War are complex. It was triggered by the growing power of both sides and, consequently, by growing mutual distrust. After the victory over Pyrrhus and his Greek allies, the sons of Wolf realized the efficiency of their army. They completed the conquest of all Italy, seizing the cities of Great Greece in the southeast of the peninsula. Over the centuries, Carthage has mastered large territories in northern Africa, Spain and the islands of the western Mediterranean basin. The Punics also conquered the western and southern areas of Sicily. Relations between the two powers began to deteriorate as Rome approached the Sicilian lands subordinate to the Punics, from which it was only separated by the Strait of Messina. For Roman politicians, the immediate vicinity of Carthage posed a constant threat to Italy, and therefore patres did not want to allow the entire Sicily to be taken over by its troops. Moreover, the capture of the island by Carthage meant the closure of the Tyrrhenian Sea to the Romans.

The direct cause of the conflict was the activity of the mercenaries from Samnium and Campania – the Mamertines, who served the tyrants of Syracuse. After the death of one of them – Agathocles, the Mamertines lost their source of income and conquered the city of Messana on the coast of Sicily, becoming enemies of the ruler of Syracuse Hiero. He defeated them in the Battle of the Longanos River but did not manage to conquer Messana, as he was beaten by the Carthaginians. The Romans also did not remain passive to the events on the island. Messana’s occupation disturbed them, and they sent their legions to Sicily. They made contact with the Mamertines who occupied the city, persuading them to capture its Carthaginian commander, which led to the withdrawal of Punic troops from here. The legions’ control of the fortress provoked Carthage’s protest, which demanded that the Romans withdraw from the city. Faced with a negative answer, the Punics began the siege of Messana from land and sea. However, consul A. Claudius, under the cover of night, led the army into the fortress and repelled many attacks by the Punics and their allied Hiero. In 263 BCE, the consul M. Valerius became the commander-in-chief of the Roman army in Messana, who finally forced Hiero to withdraw from the fortress, and then to the Punic army. The consul joined the new army of M. Otacilius, which was transferred from Italy. Both Roman armies launched a joint offensive deep into the island. Their procession was marked by successive successes, and many Sicilian cities moved to the side of Rome. They were followed by Hieron, who withdrew from the alliance with Carthage. The alliance with Syracuse allowed the Romans to obtain a base for the supply of their own army – the city was to provide the consuls with grain and fodder for horses.

Battle of Agrigentum 261 BCE

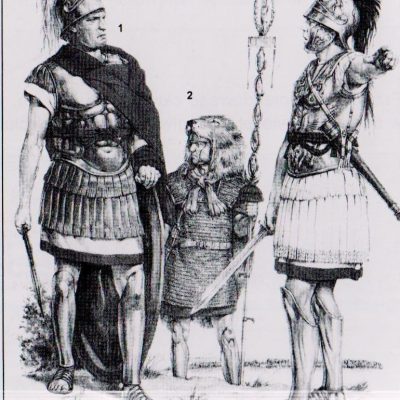

According to Polybius, after merging with Hiero, the Romans reduced their forces on the island from four to two legions in the hope of increasing resupply. While the previous victories were an incentive for them to continue the offensive, for the Carthaginians the domination of the Romans in Sicily was unacceptable. The Punics began to organize an armed expedition to the island. They enlisted many mercenaries from Spain and contingents of Gauls and Ligurians. In response to the mobilization of the enemy, the senate dispatched another four legions and two consuls to the island in 262 BCE. The main base for the Punic armies in Sicily was the city of Agrigentum (Greek: Acragas) on the southern coast of the island.

In the summer of 262 BCE, the Romans set out to the fortress. The combined forces of consuls L. Postumius Megellus and Q. Mamilius Vitulus, totalling about 40,000 people, approached the city during the harvest season. The commander of Agrigentum, Hannibal, son of Gisgon, managed to bring many inhabitants of the area behind the city walls before the siege. According to Polybius, its population has now increased to 50,000. However, the Agrigentum garrison itself was rather small. The Roman consuls camped a mile in front of the walls, and much of the legionaries scattered around the area to harvest the surrounding fields. A small detachment of armed soldiers was left to guard the camp, obliged under oath not to cease in the event of an enemy attack. The unarmed Roman legionaries, scattered across the fields and busy with their work, did not foresee an unexpected departure of the besieged. Hannibal took advantage of this situation and organized an excursion against the unprepared Romans and the enemy camp. Legionnaires sent for provisions could not resist the attackers and suffered heavy losses. The Romans guarding the camp put up a strong resistance, despite the great outnumber of the attackers. Despite heavy losses, the legionaries finally repelled the Carthaginian onslaught and drove the attackers towards the fortress.

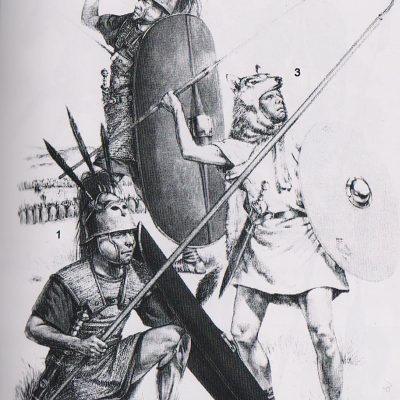

This incident forced both sides to be more careful. The Carthaginians gave up raids behind the walls, and the Romans appreciated the enemy more, better organizing the insurance of expeditions for provisions and setting up stronger guards at the camp. The mere conquest of such a large city by direct attack did not give great chances of success. It required technical skills and did not yet guarantee success. At this stage of history, the legions have not yet acquired experience in conquering great urban centres. The only thing left for the besiegers was to block the city and cut it off from outside supplies. As a result, a starved enemy would be more likely to surrender. This option was chosen by the consuls in 262 BCE. The Roman army was large enough to effectively cut off the city from external supplies. Agrigentum was surrounded by a ditch and small forts were built at regular distances along the moat. This system, called circumvallatio, surrounded the enemy from within. In addition, the second line of fortifications was erected behind the Roman positions – contravallatio, which were to prevent the supply of supplies to the city by field Punic troops. The city itself was situated on a plateau a few miles inland and had no port. So, only land forces were needed for the siege. Supplies – grain and cattle stored in the warehouses in Herbesus near Agrigentum, were provided to the Romans by allies. After five months of siege, the Carthaginian city defence commander began to see the problem of food shortages and sent out appeals for help. The Carthaginian authorities sent freshly formed troops to Sicily, which were concentrated in the town of Heraklea Minoa, where Hanno took command of them. According to Polybius, there were about 50 war elephants. Diodorus, referring to the pro-Carthaginian historian Philinus, gives the number of elephants at 60, the number of Hannon’s cavalry at 6,000, and his infantry at 50,000. The Carthaginians were thus numerically equal to the besieging Romans, and even slightly outnumbered them. Hanno first attacked and captured the Roman supply base at Herbesus, causing enemy communication lines to be cut.

As a result, the legions grouped under Agrigentum began to feel hungry, which led to an epidemic in the Roman camp. Hanno led his main forces out of Heraklea and ordered the Numid cavalry to engage the Roman cavalry in battle. As predicted, the equites took up the challenge, and when the Numidians retreated before the Roman cavalry, the enemy horsemen chased after them. As the Carthaginian cavalry neared the position of the rest of Hannon’s army, they turned back and pounced on the attacking Roman cavalrymen. They suffered heavy losses and fled towards their camp. Emboldened by this success, Hanno led his army 1 and ¼ mile from the Roman positions at Agrigentum and set up a fortified camp on a hill called Torus. According to Zonaras, the Punic chief set his forces in battle formation in front of the enemy, trying to persuade him to issue a battle. Remembering the defeat of their cavalry, the consuls did not dare to take up the challenge. After some time, however, the Romans, who felt more and more hungry, decided to face Hannon. As if stunned by the consuls’ increased zeal to fight, Hanno was now frightened of himself by the risk of a major battle. According to Polybius, the two armies stood close to each other for two months and were limited to exchanging missiles. Only the signals sent by the commander of Agrigentum to Hannon, showing the serious lack of food in the city and the growing number of desertions, forced the latter to battle. The Romans did a similar thing and, feeling hungry, decided to start. It is believed that the Carthaginian army consisted of two lines – the first consisted of infantry, the second was infantry and elephants. The cavalry has traditionally occupied the flanks. The Romans, in their custom, formed three lines – triplex acies. It is possible that the Punic chieftain’s intention was to exhaust and weaken the impetus of the legionary infantry. However, the prolonged struggle of the infantry of both sides brought an advantage to the Romans, who defeated and forced the first Punic line to retreat. The retreat of the first throw led to panic in the second Carthaginian line, which resulted in the final defeat of the entire army. Hannon’s camp and most of its elephants fell into the hands of the victors.

According to Diodorus, the Carthaginians lost 3,000 infantry and 200 cavalry, 4,000 were captured, 8 elephants were killed, and 33 were seriously injured. These data also take into account the losses suffered by the Punics during the initial driving battle. The losses of the Romans also had to be considerable. Zonaras gives a slightly different version of the events. According to him, Hannon’s attack was coordinated with the city crew’s foray. The consuls, having learned about this, simultaneously dealt with this action by the defenders of Agrigentum and with the Hannon’s army itself. According to Frontinus, Consul Postumius used a ruse to simulate his reluctance to fight a battle while remaining close to the position of the Carthaginian field army. The Carthaginians took this as evidence of their opponent’s weakness and decided to withdraw. However, they did not notice the trap set for themselves, because during this retreat, the Romans suddenly attacked them and carried out a pogrom.

Regardless of which version we consider to be true, all accounts agree on the decisive victory of the Romans. The members of the fortress’s crew, having lost hope of rescue, slipped out of the city at night. They filled the moat and broke through the positions of the besieging Romans, drunk with their victory and deprived of vigilance. After seven months of the siege, Agrigentum passed into the hands of Rome.

Summary

The victorious struggles at Agrigentum were of great importance for the Romans and their further plans. If Polybius is to be believed, the victory prompted the republic on the Tiber to completely remove the enemy from Sicily. Part of this plan was to build a fleet in order to undermine Carthage’s naval advantage around the island and in the Mediterranean in general. As for the battle itself, Carthage used elephants for the first time in combat. However, their proper guidance was impossible due to the lack of knowledge of the commanders and the inability to coordinate various army groups.

The newly enlisted Carthaginian mercenaries needed more time to train, integrate throughout the army, and get to know their commanders. It took some time for the elephants to play the role of a real “armoured fist”. In the case of the Romans, the biggest problem was the organization of the siege at the beginning and end of the fight. First, the insurance of the troops acquiring provisions failed, and in the end, the city crew was allowed to break the battle lines due to the complete lack of discipline of the victorious army.