Chapters

Roman Senate (Senatus) was a legislative and executive body during the republic, and only a legislative body during the Roman Empire. The Roman Senate was theoretically only an advisory body to officials elected by the people. However, its role expanded significantly during the mature republic. From the 1st century BCE, its importance declined decisively, and eventually, as an organ, it was only relegated to an honourary position during the empire without significant power.

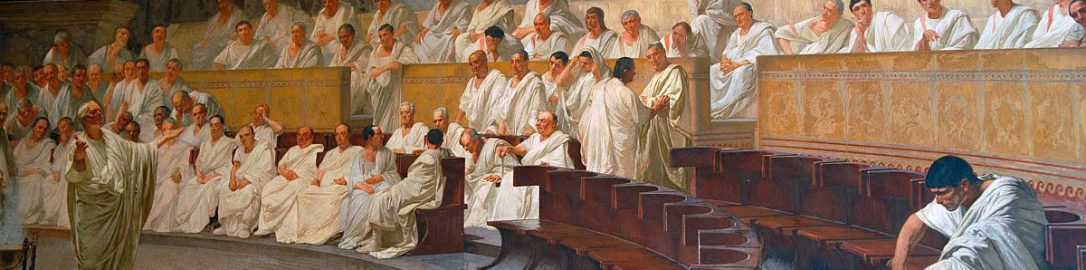

Senators were called “fathers” (patres) because of their position in the Republic and their overwhelming importance (auctoritas). The senators wore a purple tunic belt (latus clavus) and a purple leg garment with an ivory crescent-shaped buckle (mullei cum lunula) and a gold ring adorned with a precious stone (cancelus aureus). Senators’ shoes were called calcei. Regardless of the period of your country, senators have always occupied the best places in the theatre and circus.

The period of the republic

During the early republic, there were 100 senators on the council. However, this number was changed frequently. In the 2nd century BCE, the body was increased to 300. In 80 BCE under Sulla’s dictatorship 600 representatives were appointed, to increase to 900 under Caesar. Senators were elected from adult men from the most influential and wealthiest patrician families of the so-called senatorial families. The senate was open to Roman citizens of impeccable opinion who were over 45 years of age and owned a land estate of at least 400,000 sesterces. The position of a senator was for life unless a given senator was stained with disgrace and was expelled from its composition by the senate. Senators also died often in factional battles.

During the early republic, candidates were proposed by the consul and approved by the entire Senate. At the end of the 4th century BCE, the function of the consul was taken over by the censor. The selection was called lectio senatus. Former and present officials, who were entered on the list of senators, sat on the benches of the senate. The list of the senate was drawn up according to the rank of offices, i.e. from the highest one: consuls, praetors, aediles, tribunes and quaestors. The first on the list was always one of the consuls, called princeps senatus.

Decisions were made by open voting with a simple majority of votes. Senators, whether or not they walked across a line drawn on the floor of the chamber, were for or against the motion. During some important votes, there were scuffles or forcing reluctant senators to go to the right side. The quorum was different, depending on the matter discussed. If the war was debated, the validity of the deliberations required 1/?of those entitled, and if on the less important topic only 1/?of all senators were needed.

Each senator was entitled to speak once on a given matter. By law, he was not allowed to interrupt unless he had stopped giving his speech. He also had the right to say what he wanted and for how long before he got down to it. This was sometimes used to block proceedings with endless speeches. Various factions formed in the Senate, some permanent and others only to support the project. There were two permanent parties in the republic’s political system:

Optimates (optimates), or “the best”, who represented the interests of the wealthiest and influential families of Rome. It was established in the second half of the 2nd century BCE. They had support in the Senate and sought to maintain control of the state by overseeing the administration and finances of the state. In order to maintain their position, they resisted any attempts to change (democratize) the republic’s system. This party includes Pompey the Great, Cicero, Brutus.

Populares (populares) represented the interests of the commoners and the peasantry. The beginnings of the party’s activities date back to the times of the Grakch brothers (second half of the second century BCE). Its representatives did not manage to create a single program. Initially, the populares used the office of the people’s tribune to submit a veto. Populares opposed the policies of the former aristocracy. They were in favour of: agrarian reforms, the distribution of grain (bribing the proletariat by the state), rights for Italians, cancellation of court debts and the transfer of courts to equites in extortion cases in the provinces. In the later period of the republic, the leaders of the popular figures were people descending from nobles, such as the Grakch brothers, Gaius Marius or Julius Caesar. The optimists fought particularly fierce with the popular during the reforms of the Gracchus (133-121 BCE).

Senators could |

|

Senators couldn’t |

|

The meeting place of the Senate was mainly Curia (Curia Hostilia), although the deliberations were sometimes held at the temple of Jupiter Stator on the Palatine, the temple of Harmony, the temple of Castor and Pollux, as well as in private palaces.

Sessions, preceded by fortune-telling, were convened by the praetor, consul or people’s tribune, and it was the official summoning the deliberations who was the senate’s leader. It was he who, with the help of a herald, gave the senators the announcement (edictum). They were held on the first, thirteenth and fifteenth day of each month. It was possible to convene the body additionally, but only in exceptional circumstances, and the sessions could not take place during religious holidays. The assembly of senators usually lasted from sunrise to sunset, but sometimes when an important matter was discussed, the deliberations were extended until the night. Apart from senators, secretaries, messengers and liqueurs could participate in the meetings. The meeting closed with the words: The Senate and the Roman People passed (Senatus populusque Romanus decrevit).

Senate resolutions were originally not legally binding (lex or plebiscitum) and were only decisions of the senat (senatus consultum). However, along with the expansion of the senate’s powers, it gained the right to issue resolutions with the force of law. Having secured an advantage in the state, the Senate was able to take care of its interests, ie the group of great landowners whom it represented, without fear. For this purpose, he could have prevented the adoption of a motion that was inconvenient for him. In exceptional circumstances, the Senate had the opportunity to declare a state of emergency in Rome on the basis of a special resolution senatus consultum ultimum. This right suspended the activities of the authorities and allowed the consuls to take appropriate steps to restore order in the city. This facility was used many times by the Senate during the crisis of the republic in the 1st century BCE.

Empire period

After the establishment of the empire, the importance of the Senate declined significantly. It completely lost its political significance, and the election of the senator became only a kind of ennoblement. Over time, the formula of the so-called adlectio, involving the inclusion in the senate of a person who did not hold office, guaranteed entry to this institution. Apart from Rome, other important cities founded by the Romans (municipalities) had their senates. It is worth mentioning here, for example, the senate in Constantinople, which during the fall of the Western Roman Empire gained a significance comparable to its Roman counterpart.