Chapters

Everyone has heard something about Punic wars, everyone knows something. It was called the war of the Roman Republic with Carthage, a Phoenician colony that became a separate state. Qart Hadasht (New Town) was the capital of the North African country. A country that possessed great wealth, mainly thanks to its excellent fleet and well-developed trade, was second to none because of the merchants of Carthagina. But why do we call the Rome-Carthage wars the Punic? Well, because in Latin the word Punicus meant Carthaginian.

The Roman Republic and Carthage are two strongly developing countries. The Romans gained dominance on the Apennine Peninsula, while the Carthaginians were in northern Africa, as well as in Spain. Both countries soon became the dominant forces in the Mediterranean and confrontation was inevitable. The authorities of these countries were also well aware of this.

First Punic War

The First Punic War was always caused by problematic Mamertini. They were called the Italian bandits living outside the law, once hired in Campania as Agatocles’ units. The word Mamertini in their own dialect meant people of the god of war. They were stationed in Messania (today’s Messina). As I said, they caused problems forever: once they started extorting payments from Sicilian cities, other times they troubled Phyrrus (just fighting on the side of the Roman-Carthaginian alliance), but this time they had strained relations with the Greek king of Syracuse – Hieron II. So the Mamertines turned to Carthage for help against Hieron. Having achieved their goal, they decided to get rid of the Punic garrison. What did they do They asked the Romans for help. They were aware that, despite the not-so-old alliance with Carthage (made against Pyrrus), this is still a great threat. A threat that is very close, because just behind the narrow Messina Strait. The opportunity to eliminate Carthaginians from the fight for primacy in the Mediterranean basin seemed very tempting and the Romans decided to use it. They made a covenant with the mottines, who, encouraged by an alliance with a strong state, expelled the Carthaginians from Messania. In this arrangement, the Carthaginians began to cooperate with Hieron II. Their troops launched an attack on Messania. In that case, it can be said that then the war had already begun. Its full beginning, however, turned out to be the arrival of the Roman army to Sicily under the leadership of the then consuls. Forces of the Republic wanted to free an allied city from the attacks of an enemy army.

Two extremely interesting and extraordinary situations are associated with the Punic Wars. Carthage, which had most of its mercenaries and its own troops, did not have enough, gave two very capable leaders, namely Hamilkar and his son Hannibal, from the Barkid family. In turn, Rome, having virtually no maritime traditions, hastily built a more powerful than Carthaginian fleet. How did this happen? There are two versions of this event: the first says that the Romans found the wreck of the Punic five-rower and based on it (almost serial) production of their penthouses. The second says that Hieron of Syracuse, after entering into an alliance with the Republic, gave the Romans important advice on shipbuilding, and also provided his own five-rowers for copying.

Let’s return to the course of events. The Roman army, led by two consuls – Appius Claudius Caudex and Manius Valerius Maksimus freed Messania from Carthaginians, and Maximus was given the nickname Messall. After the beating of the Carthaginian and Syracuse forces, the cautious Hieron II abandoned the Carthaginians and joined the alliance with the Romans in 263 BCE. In 262 BCE, the Roman army captured Segesta in the northwest of Sicily. However, it was not the end of the march through the island. After a heavy siege, under Roman pressure Akragas (Agrigentum) fell – a city in southern Sicily. However, the Punites did not want to step down and the Romans understood that they would not win this war if they did not become a worthy rival for the Carthaginians at sea – because Kart Hadast is in Africa, so Rome would not pose a direct threat to the enemy. This is the situation I discussed earlier – the rapid building of the fleet by the Romans. The work was wonderful and the effort great. If we should learn something from Rome, it is determination and relentless pursuit of the goal. For how, without these two features, could a state with virtually no maritime traditions build a fleet more powerful than that of Carthage’s naval power in a short time?

The Roman fleet had 160 ships. In addition, the Romans equipped their ships with so-called ravens, about which in a moment. Gajus Duilius was the commander – in 260 BCE, Polybius said that when Gaius Duilius learned about the ravaging of the enemy army by the enemy army, he led the entire fleet there. The Carthaginians were in great moods, they sailed their own way, with the strength of 130 ships. Very confident, they behaved like a lion getting ready to eat. After all, an antelope will do him no harm. However, the Romans entered the battle with respect, regardless of the 30 ships’ superiority, it can be said that Carthage was the favourite for victory. However, she made a serious mistake – disregarding her opponent. The Punnians did not even line up for battle. As they approached, they saw the bizarre bridges raised up ahead of the ships. They were ravens. They did not care too much, “land people” will not be able to defeat maritime power. They attacked the Romans with full boldness and exaggerated faith in their own strength. At that time, these bizarre (from the Carthaginian perspective) bridges fell on their ships. In turn, Roman soldiers began to run after them, the infantry, which probably exceeded all the infantry of the world at that time. Punnians, surprised, we’re unable to resist the Romans in the fight on board. They didn’t match them in this craft. They died or gave up. They lost 30 ships with the crew, also the ship of the chief – Hannibal, son of Giskon (not to be confused with Hannibal Barka, son of Hamilcar). Hannibal managed to escape on a small boat. Meanwhile, more Punic ships came in. Seeing the fate of their predecessors, sailors strayed from the road to avoid ravens. They wanted to attack enemy units from the side or from the back. However, Roman ships with these bridges were almost everywhere. If the Carthaginians came closer, they were immediately attacked and caught. The Carthaginians accepted the severe defeat, all the more overwhelming since it suffered at sea. They lost 50 ships, and the commander along with the rest of the property sailed to Carthage. The Romans won a great victory. The great first sea victory over the mighty Carthage. For the winners, this was proof that the enemy could be defeated, while for losers – a cold shower. Very cold, I would say cold. However, this was not the end of the catastrophes that fell on the great Carthage. In 256 BCE, another great sea battle took place at Cape Eknomos on the southern coast of Sicily. And again the Punnians’ fleet was devastated, even more so than under Mylae, because the Carthaginians lost as many as 80 ships. What shock the politicians in Carthage must have been when they learned that they, the sea empire, were experiencing another humiliating defeat at the hands of their greatest enemy and a sea rookie in addition.

However, the Romans decided to follow the blow and wanted to destroy the city of Carthage with victorious impetus, which is why in the year 256 BCE the Romans blew up their troops on the coast of Africa. Army of the Republic began to wander to the enemy capital. This time, however, the Carthaginians did not ignore the rival, whose greatest strength was the fight on land. Using their vast wealth resources, they employed the talented Spartan chief Xantippos. He trained the Punic army and it represented much more combat value than before the training. In 255 BCE there was a battle in which the Carthaginians defeated the invaders led by Consul Regulus. Roman infantry was surrounded by Carthaginian cavalry and smashed by it. Regulus was taken, prisoner. As if the misfortunes were not enough, the storm shattered the fleet, which the Romans sent to save the survivors of Regulus’s army.

In 254 BCE, the Romans attacked and captured the Sicilian city of Panormos (today’s Palermo) belonging to Carthage, located on the north coast of the island. The fights that took place during the First Punic War were very fierce. Four years after the loss of the city, the Carthaginians launched an attack aimed at rebounding Panormos, but it was repulsed by Lucius Caecilius Metellus, who after the victory moved into a counterattack and encircled two West Sicilian cities, and they were called Drepana and Lilybaeum (located on the western cape of Sicily about the same name as the city). In 249 BCE the tide of victory again tipped over. Publius Claudius Pulcher tried to capture the city of Drepana by an attack from the sea, but he failed to do so, moreover, the storm crashed the rest of the Roman fleet on the southern shore of Sicily. Later, however, the Romans began to win again. They conquered the mountain and the city of Eryks in the west of Sicily. The capture of Eric caused Drepana to be cut off from land roads. Returning, however, to the fortress in Lilybaeum, the Romans besieged and tried to capture this city for a very long time, for as long as 9 years, i.e. until the end of the First Punic War. Above all, dominating the sea was crucial to the course of this war. Because the Romans besieged Lilybaeum did not have to end the war yet. They knew this, without forgetting, of course, that they had to face the mighty Hamilarek Bars – an excellent commander, whose disregard or let him flash a genius could have tragic consequences. So it was necessary to set up a new fleet and cut off Hamilkar from possible meals from the capital of his country. The new fleet, because previous storms have suffered numerous storms. It was built in 242 BCE. Gajus Lutacjus Katulus, who was then a consul, took command. He decided to issue a great battle of the Punic fleet, which appeared near the Aegean Islands on the west coast of Sicily in 241 BCE. I will just say that the Carthaginian fleet was completely broken up, and this was probably on March 10.

As soon as the Carthaginians found out about the defeat, another one, they sent a bishop to Hamilkar to tell him that from now on Barkas has the full right to decide, he became the most important figure of Carthage. According to Polybius, Hamilkar did bravely and correctly. As long as there were no chances for a positive outcome for the Carthaginians, he fought hard and resisted the Romans. However, when everything that Barkas had in store failed and there were no prospects for success, he sent deputies to Lutacjus. They were to convey that Carthage wanted peace. Lutatius agreed for Rome seemed to be wary of the constant struggle against Carthaginians. However, he reserved the Roman that his decision must be confirmed by the consent of the Roman people, then it will be binding. And so ended a long and tiring (264 – 241 BCE) war called the first Punic War. However, this is not the end of my story, because it is worth mentioning the difficult conditions of peace that Rome imposed on the lost Carthage. The Carthaginians had to leave Sicily completely, not wage war against Hieron II, as well as against Syracuse, which he ruled, as well as their allies. The Carthaginians were also to give the Romans all prisoners without ransom and pay a gigantic contribution – 3200 talents of silver (within 10 years). Assuming that talent weighs 26, 12 kg, one can count that Carthage had to pay about 83.5 tonnes of silver. The Punnians were a rich nation, but this amount had to impress them.

After the First Punic War, both countries returned to their problems. It can be said that they would immediately take advantage of their rival’s weakness, but they had to deal with their own troubles. And so the Romans managed to hit the Carthaginians quite hard. So let’s talk a little about the troubles of the Carthaginians. A mercenary revolt broke out. In another country, there would be no tragedy from it, however, as we know in Carthage, they constituted the backbone of the army, so the problem that arose was a problem of a very large calibre. Carthage survived the uprising only thanks to Hamilcar’s commanding skills. Carthaginian mercenaries from Sardinia were summoned there … Romans who took the island. When the Carthaginians began to protest, the Romans hypocritically threatened Carthage with war and forced it into something of a kind of unconditional surrender, Corsica and another 1,200 silver contributing talents to give up the island of Sardinia. However, Hamilcar saved his homeland from a collapse that might have resulted from a rebellion. His name slowly became legendary, but he never gained much fame as his legendary son, Hannibal. After the First Punic War, Syracuse retained independence, which was connected with Rome by an alliance. Now let’s move on to Rome’s troubles because these were not small ones either. In the north of Italy, more battles with the Gauls were undertaken. The Romans also had to subjugate the Illyrian queen, because she, instigated by Macedonians, extended her power to the south and actively supported piracy, as it was the backbone of the Illyrian economy. Of course, Rome did not profit from Illyrian piracy, it brought considerable losses, so this practice had to be curtailed, which was done by the extremely consistent Romans.

In 238 BCE, relations between Rome and Carthage again became very tense. The merchant power realized the strength of the Romans at sea and ceased to expect eternal peace. Carthage was getting ready for war. Great Hamilkar, with his talented young son Hannibal, who was beginning his great history, appeared on the Iberian Peninsula, where they began to expand Punic influence. They occupied the city outside the city, conquering new areas making Carthage an increasingly stronger state. Hamilcar treated Iberia not only as an area of economic expansion but also as a military base from which it would be good to strike Rome. Great Hamilkar, however, fell. Maybe in battle, maybe it was a murder, we won’t find out. In any case, the young angry Hannibal, still in his father’s lifetime, promised him eternal hatred of Rome and that he would do his best to destroy his greatest enemy, the greatest superpower of the world at that time – the Roman Republic. Hannibal walked and occupied everything in Iberia that got in his way. His hatred of Rome was burning in his mind. Actually, he did everything to hate Rome, which gave him strength. On his way through the Iberian Peninsula, he finally came across Saguntum – a city with trade links with Massilia and an alliance with the Romans. Saguntum resisted for 8 months, then gave up. The conquest of Iberian cities lasted a long time, because in the years 237-219 BCE In the meantime, young Barkas married the Iberian princess, which, however, did not prevent him from defeating the local tribes. Hannibal knew that by his actions he had attracted the attention of the Romans. So he decided to strike before Rome reacted.

Hannibal ante portas!

Hannibal neglected Iberia. At the head of 35-40,000 men, he headed for the Rhone. He also ran elephants. We all know that Hannibal marched with his army across the Alps. It was a great and extremely risky undertaking. With this crazy manoeuvre, he wanted to surprise the Romans, who expected that Barkas would walk along the coast. Hannibal counted on the fact that he would feed his army with the help of the Gallic tribes occupying the lands through which he crossed. The Gallic tribes, however, had different relations with the Punic chief. Some helped, and some tried to resist the great army marching through their territory. The tribe who lived in the Rhone valley, the place where the Carthaginians wanted to cross, also had an unequal attitude. The inhabitants of the west bank helped as much as they could, even building all sorts of boats for Hannibal to get his troops across. Already at this point, it was getting interesting because the Gauls from the eastern bank of the Rhone were blocking the Carthaginians’ crossing. For the brilliant Barkas, however, it was not a major problem, he dealt with them in an effective manner. He sent a small detachment of Bomilkar to the other side, led by friendly Gauls. They crossed the Rhone a day’s journey upstream where the island lay in the middle of the stream. The cavalry has gone on rafts, and the Iberian infantry has gone … on their own shields. The entire operation was carried out at night so that the opponents would not find out about it. As Hannibal’s main force began their crossing, the hostile Gauls realized that they had been surrounded by Bomilkar’s unit. They began to run away in panic. The Carthaginians crossed the Rhone. Only three days later, the Roman army under the command of Scipio (who was the father of the legendary African Scipio) landed in Massilia. The Romans counted on the capture of Barcaras, but the Punian camp was already empty. Scipio decided not to pursue the Carthaginians, but to go to Iberia to cut Hannibal from any reinforcements that could be provided by the garrisons left in the Iberian Peninsula by the young Punic chief.

The March through the Alps is an epic tale, full of drama and maybe even twists and turns. Hardly anyone could be tempted to such an undertaking, but Hannibal proved that with his genius he also does not lack a note of madness. Barkas was ready to risk everything just to destroy Rome. Despite his young age, the Punic chief was impressive with his incomparable intellect. He has shown many times that he is willing to take great risks. If I were to compare Hannibal’s literary hero to some, it would be certainly Richard Rahl with the “Sword of Truth” by Terry Goodkind. Both of them did not treat the surrounding ± more reality ś you in terms of “possible” and “impossible.” Hannibal was famous for unconventional and non-standard thinking. Certainly, soldiers often asked Barkas the question: “How will we surprise the Romans, since they know that we are here and confidently set the road?” Hamilcar’s son would certainly answer: “They blocked all passages? Let’s go where there is no passage!” Summing up some information about the psychological profile of Hannibal, it can be seen that he was an extremely brave, creative and risk-taking man, but above all, he was extremely hateful to Rome. As for crossing the Alps, even Livius, who was not famous for his favour with Carthaginians, was very impressed with this achievement. Historians from ancient times argue about the place of crossing the Rhone and the Alps by the Carthaginians, so we can not clearly assess where it took place. It is certain, however, that Hannibal did not march to the Alps by the shortest route. Carthaginians went up the Rhone for four days. After this time, they managed to gain the support of one of the Gallic tribes. This was because Barkas successfully settled the dispute over the succession of tribal leadership.

It is estimated that Hannibal lost over 25% of his army while crossing the Alps. When at school it was told how Carthaginians crossed the mountains and how many died at the same time, before my eyes appeared the image of soldiers who were bravely marching through narrow passes, who suffered from the great frost. A strong wind blew their faces, throwing snow at the same time, and huge avalanches fell from the slopes, huge masses of snow pushed hundreds of soldiers into the ice chasm of the Alps. However, it was not like that. The cause of death for so many people was definitely more military. Certainly, some soldiers died from exhaustion or because of slipping and falling into the abyss, but very many people lost their lives as a result of the betrayal of Carthaginians. Climbing the northern slopes of the Alps, the Carthaginians were betrayed by the Gauls, who set a tragic trap for marching soldiers. I immediately point out that in this article I will not include descriptions of the battles, because for this purpose I will write a separate work, in which I will say something about this trap, as well as about the battles, among others on Trebia or the Ticinus River.

The Carthaginians descended to the Italian side with the first autumn snow. Landslides, gulfs and great frost hindered the army’s march. It was really miserable when the road was blocked by a large rock. Carthaginians, however, chopped wood and lit a large bonfire. The soldiers also poured their rations of sour wine onto a hot boulder to crush it. Further on, Hannibal’s people descended along the bends on the mountainside. The Carthaginians arrived in Italy five months after leaving Iberia. The hell of crossing the Alps lasted 15 days. When it comes to the number of soldiers carried out by the mountains, the ancient descriptions are not the same here. Polybius, drawing data from the inscription left by Hannibal in northern Italy, says that it was 20,000 infantry and 6,000 cavalries. Livius is based on the data of the historian Lucius Cincius Alimentus, who for some time was a prisoner of Barkas. However, he believes that the numbers of Alimentus, or 80,000 infantry and 10,000 rides are exaggerated. As I have already mentioned, it is estimated that Hannibal lost about 25% of the army during the march through the Alps, and maybe more. It is certain, however, that even such large losses were not treated as preventing further campaigns, especially for such a brilliant and motivated by such a great hatred leader, which was Hannibal Barkas. As a fact, it can also be said that for the next 15 years of fighting in Italy, despite the fact that Hannibal’s genius on the battlefield shone brighter than most of the Milky Way stars, the great problem of the Punic chief was the recruitment of soldiers, was finally on enemy territory. Barcids’ other troubles were no less serious, as it was about acquiring allies and receiving new supplies – such a large army would not feed itself.

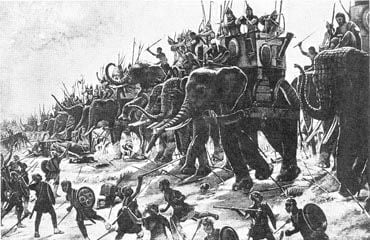

In 218 BCE, the consul, Publius Cornelius Scypion, sent the army under the command of his brother Gnejus to the Iberian Peninsula, while he himself went to northern Italy, where he took command of the legions. He encountered the invasive army of Hannibal, which had already occupied the area of today’s Turin, in the corner formed by the Po River and its tributary, Ticinus. Over Ticinus there was a battle in which Hannibal’s ride pushed the Romans’ ride back. Scipio was wounded. It is also said that Scipio’s life was saved by his 18-year-old son (later Scipio Africa). Scipio, who commanded the army, withdrew with the army to Placencia (today’s Piacenza). The clash showed the superiority of Barkas’s ride over the Roman one, which is why the consul decided to avoid open spaces convenient for cavalry. In the face of the Cartaghinian attack, the second consul, Tiberius Sempronius Longus, who was preparing to invade Africa, moved north to join his army with Scipio’s army. Due to the serious wound of Publius Cornelius, Sempronius took command of the entire army. His cavalry had a skirmish with Punic in difficult winter conditions, and the consul, encouraged by a positive result, fought a large battle over the southern tributary of the Po – on Trebia. Hannibal personally explored the area and decided to prepare a nasty surprise for the Romans – he set up an ambush, which he masked thanks to the nearby thickets. The Romans lost as much as 2/3 of the army, but fortunately, 10,000 legionaries broke through the Carthaginian centre, breaking free from the lap. They found shelter again in Placencia. The Carthaginians captured a lot of Roman horses, but they were still terrified by the sight of elephants, which could have unpleasant consequences for the Carthaginians in later clashes. The Romans, in turn, had to recall the way elephants were scared away when Pyrrhus’s Epirus-Tarantian troops invaded Italy. Velites were traditionally supposed to play a major role in driving these giant animals away. They pricked elephants with their javelins (verutum) around the rump – the only place where the elephant has soft skin, and screamed, almost causing panic. The arrival of winter meant that Hannibal decided to wait out the winter. When he took the march south in the spring, his army was struggling to walk through the areas flooded with melting snow. What’s more, the Punic chief fell ill with eye inflammation, as a result of which he blinded one eye. Hannibal rode on the only surviving elephant whose back was relatively dry. Other elephants fell in battle or could not withstand harsh weather conditions.

Publius Cornelius Scipio was sent to Iberia with new guidelines, in Italy a new consul, Gnaeus Flaminius, guarding the Western Apennines, decided to follow Hannibal’s army. Barkas, however, reached the level of ambush master. Carthaginians planted the Romans on the northern shore of Lake Trasimeno in Etruria. The Romans marched in the narrowing between the hills and the lake. The Punic army hid in the mist covering the hills and waited for the Romans to cross the area between the hills and the water. As the Roman army chased Hannibal and advanced, entering the ambush, Carthaginian troops hidden behind the fog fell on the legionaries’ surprised and unsuspecting. The Punnians pushed the Romans into the lake and made a terrible carnage amid great confusion and terror. Two Roman legions ceased to exist, Consul Gnaeus Flaminius was killed. After this devastating defeat, the Romans, led by the second consul, again fell into the trap of losing 4,000 rides. The situation was exceptional (after all Rome had not received such beating for a long time), so the need for a uniform leader was understood. The dictator was elected. It fell on Quintus Fabius Maximus, called the procrastinator (Latin delaying). This nickname refers to the tactics he used against Hannibal. He sought to avoid direct clashes with Carthagininas because the Romans simply didn’t have a way. The procrastinator also wanted to delay Hannibal’s march, prevent him from replenishing his supplies, and harass the Punic army as much as possible.

Meanwhile, Hannibal was looking for his allies – some Gauls enlisted in his army, but many tribes were no longer willing to support Barkida. In this situation, the Carthaginian leader decided to find support in southern Italy. However, he was even less fortunate there. He also tried to get Fabius Maximus to take up the battle, but he used the proverbial procrastinative strategy. Hannibal attacked and plundered Apulia and Campania, which caused dissatisfaction with the procrastinator’s strategy. Consuls were re-elected. The Romans gathered their entire army, and the consuls – Gaius Terentius Varro and Lucius Aemilius Paulus – joined the army of consuls from last year – Servilius and Atilius. The Romans put up a huge army because Polybius says that it had 80,000 walkers and about 6,000 horse-drawn. Polish historian Zygmunt Kubiak believes that Polybius overestimates the size of the army of the Republic. Kubiak writes in the History of Greeks and Romans that the Roman army had 48,000 infantry and 6,000 cavalries. Suppose, however, that Polybius is right here. In any case, the army of Romans suffered even more than a devastating defeat at Cannae (Latin: Cannae). Actually, it’s hard to find words that would convey such a catastrophe. And at Cannae, it was not without Hannibal’s deception. What did Puńczyk figure out this time? Well, 500 mounted Numidians pretended to pass to the side of the Romans, and they abandoned their weapons. It turned out, however, that they had a second weapon hidden under their clothes, which they did not fail to use, wreaking havoc at the back of the Roman army.

Hannibal was a leader who paid attention to literally all factors, including atmospheric, which could have any significance in battle. He also knew the weather well. Over Trebia, in frosty weather, Punic soldiers were well-nourished and oiled to maintain muscle function in the bitter cold. The Romans, however, fought hungry and cold. At Lake Trasimeno, Hannibal used the fog and set up his army at Cannae so that the wind would blow towards the Romans, driving dust clouds on them.

Let’s take a closer look at Hannibal’s troops. They consisted mainly of mercenaries. Polybius reports that over 12,000 African Africans, 8,000 Iberians and 6,000 horsemen consisting of Numidians and Iberians passed through the Alps. After crossing the Alps, Gauls and Italians joined the army. Iberian infantry consisted of Balearic slingers, light-armed infantry armed with small round shields – caetrati, and scutaria – heavy-armed infantry armed with a short sword, spear and heavy pilum or saunion (heavy weapon made entirely of steel). Scutaria protected themselves with their long, flat shields – scuta. According to Polibius’s description, soldiers of the Iberian infantry wore white tunics with a purple finish, but it was not purple, but a mixture of scapula and indigo. The helmets were typically Iberian, it can be said that it matched the skull exactly. Iberian’s helmets didn’t have any headdresses or anything like that. The Ibers also wore homemade shoes. It happened after the battle that they took the fallen Romans’s armour and helmets and used them in subsequent clashes. As for African or Numidian riders, they were so good at horse riding that they did not use a bridle. Their shields were quite small, unlike the javelins, which were really substantial. They looked similar to scutaria and caetrati. The Numidians played an important role in the Punic army, and Hannibal highly valued their services. The African infantry was a mix of Carthaginians and Libyans. Originally it was armed with a Hellenistic pattern, but after the first triumphs of Hannibal equipped it with Roman weapons, because it was of better quality. The Romans were also taken from armour and chain mail, but it should be noted that the Africans did not take Roman shields, but remained with their (Greek type), probably because they were not mistaken for the Romans and were not killed.

After the Canna massacre, Kapua and many other cities and towns in the south of the Apennine Peninsula crossed to Carthage. The Romans attacked and besieged Kapua. Hannibal wanted to distract them from the city, so he made a maneuver simulating the march on Rome, only that the Romans surprised Barkas and did not react as expected. Hannibal could no longer come to the aid of Kapui and left her at the mercy of the Romans, leading his army out of Puglia. One of the commanders in Hannibal’s army. Maharbal, even begged his leader to march on Rome. However, when Barkas did not do it, memorable words were spoken: “You can win Hannibal, you cannot use victory”. While in Italy Hannibal beat the Romans as he wanted and where he wanted, in Iberia the brothers Scypionowie, Publius and Gnejus, fought a successful campaign against Carthaginians. However, in 211 BCE, without receiving additions, they were defeated and killed. Later that year, Publius’ son, Publius Kornelius Scypion, called the African, landed on the Iberian Peninsula. He headed quickly towards New Carthage (today Cartagena) – the capital of Carthaginian estates in Iberia. The city was conquered, but Scipio failed to prevent Hasdrubal Barkas, brother of Hannibal, from crossing the western Pyrenees with reinforcements for his brother’s army fighting in Italy. Hasdrubal wintered easily in Transalpine Gaul (southern France) and crossed the Alps in a more friendly time of the year than Hannibal did. In addition, the Gallic tribes did not bother Hasdrubal, because they were convinced that his goals lie far to the south. However, not everything went according to plan, and actually, nothing went as intended. Hannibal was amazed at the speedy arrival of his brother to Italy, he remembered what problems he had experienced. Meanwhile, the Romans intercepted messages from Hasdrubal to the second of the Barkas, and two consuls – Marek Liwius Salinator and Gajus Klaudius Neron – managed to secretly unite their armies. Neron, despite his rather gloomy disposition, showed a rare initiative to cooperate with the second consul. Hasdrubal encountered a Roman army in 207 BCE on the Metaurus River in Umbria. He didn’t get any help from Hannibal, because he, surprised by his brother’s quick arrival, was late. Hasdrubal suddenly realized that he had to fight two Roman armies, not one, he thought. He tried to retreat, but Rome’s superior forces surrounded his army and he had to accept the battle in adverse conditions. The Romans achieved a complete and indisputable victory, 10,000 out of about 30,000 Carthaginian soldiers fell, and Hasdrubal was killed if that was not enough. Hannibal could not count on supplements from now on.

In turn, Scipio, who was brilliant in Spain, crushed two Carthaginian armies there. He did so using a new method, namely binding the enemy centre with a fight and surrounding it through fast wings. Scipio returned to Italy as the winner of the war in Iberia. He found himself in opposition to the tactics of Fabius Cunctator. If Hannibal could not count on supplements and Iberia was taken by Rome, it is time to retaliate. Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus the Elder received permission to attack Africa. His campaign began with failure because he failed to capture the city of Utica, which lies on the coast northwest of Carthage. Scipio decided to wait the winter on the coastal hills. When the winter was over, the Romans defeated the Carthaginians and their ally, King Syphax, in a battle on the vast plains deep in North Africa. Carthage was in serious trouble. So serious that Hannibal was dismissed from Italy. The arrival of Barkas, despite ongoing peace talks, resulted in the resumption of hostilities.

Fighting in Iberia, Scipio won a very important ally for Rome. It was Masynissa, a young Numidian prince who had fought on the side of the Carthaginians. Thanks to this, the Romans received very important support in the form of a Numidian ride.

Soon, in 202 BCE a decisive battle took place. The Romans under the command of Scipio Africanus clashed with the Carthaginians of Hannibal Barkas. Two brilliant leaders could finally fight the most important duel. Two armies met at Zama. Determining the exact place of the battle is extremely difficult, as the name “Zama” was then carried by several places in North Africa. The battle went very well for Scipio – the Romans won the clashes of cavalry on both wings, and also chased away the elephants. So now Scipio was able to perform the manoeuvre that plunged the Punic forces into Iberia – to bind the centre of the Carthaginians and surround them with cavalry. It became nervous for the Romans when it turned out that the Roman and Numidian cavalry had gone too far in pursuit of the fleeing Carthaginians, the Moorish and the Numidians who remained faithful to Carthage. The battle of the infantry lined up in one line (both with the Romans and with Hannibal) was very even, but in time the cavalry under Rome returned and struck from the rear on the army of Barcas, shredding it to shreds. This time it was the Romans who made the slaughter. Hannibal and the few horsemen managed to escape to Hadrumentum on the coast and then to Carthage, where he was advised to sign the peace. 20,000-25,000 Punic soldiers died in the Battle of Zama, and 8,000-10,000 were captured. Rome’s losses are about 2,000 dead, 2/3 of which are Masinissa Numidians. It was after this battle that Publius Cornelius Scipio was named African in Rome.

Perhaps we should study the provisions of the peace made after the Second Punic War. Carthage renounced its fleet (except for 10 three-row ships), it also gave up elephants, prisoners and fugitives for the entire duration of the war. She relinquished to Rome Spain and had to pay the Romans a contribution of 10,000 talents, probably silver. Fortunately for the Carthaginians, the Romans spread this sum into annual instalments. The losers were to pay the full amount within 50 years. Carthage retained possessions only in Africa. Nor could it wage wars outside Africa, and in Africa – only with the consent of Rome. The only plus for Carthage seemed to be leaving Africa by the Roman army. At least for now… And in Africa remained Rome’s ally, King of Numidia Masinissa. As a faithful ally of the Romans, he was a mighty ruler, the greatest of the Numidian kings. And Carthage couldn’t help but Masinissa subjugated Numidia to new territories at her expense. All complaints to Rome resulted only in sending Roman commissions to supervise compliance with the provisions of the peace. However, such commissions only agreed with Masinissa or left the matter pending, Numidia was, after all, a great ally for Rome, so it was advantageous to maintain friendly relations with her.

Third Punic War

Carthage, however, survived the Second Punic War. Mainly thanks to Hannibal, who was in favour of signing peace with the Romans. Peace, the swallowing of which was certainly very difficult for Barkida, as he probably imagined Rome conquered by him, the greatest enemies on his knees, and yet it was him who had suffered defeat. Hannibal, however, did not rest on his laurels but began to reform the country so that Carthage would become a power again, and not a state that cannot cope with Numidia. Barkas changed the law, weakening the power of the oligarchs, changed the financial regulations, and ordered to build of better roads for the development of trade and agriculture. But when things are going well, there will always be someone ready to spoil it. Hannibal’s political opponents told the Romans that Barkas was plotting with Antiochus III Seleucid. A Roman commission arrived at Carthage, but Hannibal managed to escape from Kart Hadasht. He reached Antiochus and incited as much hostility towards the Romans as he could. He asked Seleucid for military help, and he himself was ready to once again inspire the Carthaginians with the vision of his dream of a defeated Rome and invading Italy again. However, Hannibal was not doing as well as before. His hopes were brutally shattered by the Rhodes fleet, which defeated Hannibal (near the city of Side, 190 BC) in a small naval battle. Hannibal fled to Crete and from there to Bithynia in Asia Minor when he learned of the defeat of Antiochus with Rome at Magnesia in the same year. In Bithynia, Hamilcar’s son once again tried his luck. He urged King Prusias I to defend himself against the attempts of the king of Pergamum allied with Rome – Eumenes II. Prusias, however, suffered a defeat against Pergamon in 184 BCE. About a year later, Hannibal Barcaras, chased by the vengeful Titus Quintus Flaminius (the victors of Macedonians from Kynoscephalai), committed suicide by taking poison, fearing being handed over to the Romans. What an epic and dramatic story the life of Hannibal Barkas is.

Carthage, on the other hand, was repeatedly harassed by Masinissa, but the trade was still successful for the Carthaginians. The city grew, but it was militarily weak – after all, it had been disarmed by Rome, and people had become accustomed to fighting. On Masinissa’s provocations in 150 BCE, The Carthaginians decided to respond militarily. However, the Numidian army smashed the Carthaginian army to dust. This battle was a good pretext and justification for the Romans to declare war on the Carthaginians because they broke the provisions of the peace treaty – they conducted military operations in Africa without Rome’s consent. The Greek historian Appian describes that the Roman envoy who brought the Carthaginians news of the declaration of war also said that the Roman fleet was on its way. Terror prevailed among the Carthaginians, emissaries were sent to Rome asking for peace under all conditions. The Romans ordered the Carthaginians to send to Sicily, to the consuls, 300 hostages – the sons of the most important families. They would have done it in a month. And the hostages were handed over to the Romans amid the weeping and wailing of their mothers and their families. The consuls took the hostages and sent them back to Rome. These consuls – Manius Manilius and Lucius Marcius Censorinus – soon landed in Africa, in 149 BCE. The Roman infantry under Manilius’ command has spread out more or less where they were once camped after the victorious Battle of Zama. The ships, under the command of Censorinus, stopped at the port of the city of Utica. When Punic emissaries arrived in Utica, they heard from Censorinus that the Carthaginians were to surrender all missiles and catapults in the capital, whether public or private. And the emissaries agreed to it. According to Appian, two Roman officers travelled to Carthage along with Punic envoys and picked up loads of javelins, missiles, and nearly 2,000 catapults. With all this, and also with Carthaginian dignitaries, they returned to Utica. Important personalities of Carthage hoped that they would be respected, but Censorinus praised their obedience and ordered them to carry out one more order from the Roman senate – they were to hand over Carthage to the Romans and live anywhere in their country, as long as only 80 furlongs from the sea. The Romans planned to destroy Carthage. The dignitaries threw themselves on the ground, beating it with their hands, and insults against the Romans fell frequently and densely. Some have torn their robes (it is reminiscent of Rejtan) and even self-mutilated. The Romans, however, did not react, so the Punic dignitaries returned to their capital. And riots arose in the city, councilors were torn off, advising them to hand over the hostages and give up their weapons. Others threw stones at the envoys. The capital city was boiling with rage and panic. On the same day, the Carthaginian council freed all slaves, who thus became Punic soldiers. Who would become the leader of a city in desperate need of a good general? The choice fell on Hasdrubal (not Barkas, of course), who lost in 150 BCE with Masynissa. He was sentenced to death in Carthage, but he fled and now he has to defend his capital. He already had 20,000 men in the army, but they still had to be armed. In Carthage, work is in full swing, even in the sacred groves. Everyone, men and women, worked hard. Appian reports that 100 shields, 300 swords, 1,000 catapult missiles, 500 spears and javelins were produced daily, as well as as many catapults as they could make. The Third Punic War was about to begin and Carthage was going to be ready for it. In 149 BCE Hasdrubal twice pushed the Romans away from Nepheris, a fortress built on a seaside rock. However, the real warfare began only when Publius Cornelius Scipio Aemilianus, son of Emilius Paulus (conquerors from Pydna) and grandson of Scipio Africanus, arrived at the walls of Carthage. With the beginning of spring, Scipio stormed the castle of Carthage, known as Byrsa. There were three roads leading from the square to Byrsa, built up on both sides with six-story houses. The Romans seized the first houses and attacked those who stood on the tops of further buildings. Once they mastered them, they threw beams and boards over the narrow streets and walked over them as if on bridges. Under the battle on the rooftops, a battle was fought in the narrow streets. Soldiers fighting below were often surprised by corpses falling from roofs. Only after reaching Byrsa, did Scipio order the houses to be set on fire so that the next troops could go through the ash, and not through narrow streets and roofs. Many people died then. For those who wished to leave Byrsy, Scipio was guaranteed safety, as requested by them. Thus, 50,000 people were led out and placed under guard. 900 Roman fugitives took refuge with Hasdrubal, his wife and two sons at the temple of Eshmun. It was entered after 60 steps, so despite the small number of defenders, the attacks on the temple were repelled. Only tormented by hunger, fear and lack of sleep, they retreated to the temple itself, some climbed onto the roof. Hasdrubal surrendered and was spared for the day of Scipio’s triumph in Rome, while the wife and children of Carthaginian preferred to die in the flames of the burning home city. In John Warry’s “Armies of the Ancient World”, we can also read about how the Romans themselves found themselves in real danger before the conquest of Carthage, during the siege. Conquering the 14-meter-long city walls was not an easy task for the Romans. The Carthaginians managed to successfully block the Roman soldiers – they cut them off from the sea. The resourcefulness and sober mind of Scipio Emilianus saved them from the oppression of the Republic soldiers, who had a pier built across the bay with the Carthaginian port. In this way, he cut off the Carthaginians from the sea. They, in turn, came up with the idea to dig a canal from the inner, military harbour towards the coast and sail out into the wide water. As they thought, they did so, except that the Romans defeated them in a naval battle and then breached the walls. Thus the oppression of the Romans ended and the hell of the Carthaginians began. As Appian presents, Scipio looked at a city that was a power for several centuries, was resourceful and thriving, which for three whole years fought valiantly against a terrible siege, and wept. He wept over the fall of this wonderful Carthaginian civilization and remembered the fate of Troy. And then his master and friend – Polybius – stood by Scipio. Scipio was to recite the lines of the “Iliad” and explain to Polybius that they meant his (Scipio) fear for the fate of his homeland because before his eyes he had an image of fallen powers such as Assyria, Persia, Macedonia and Carthage. Either way, after a three-year siege, in 146 BCE, Carthage was annihilated, and it ceased to exist. Forever…