Perpetual lease, a type of limited property law, significantly evolved in Roman law with the passing time. Initially, a lease in the form of ius in agro vectigali has appeared as a law separate from the ordinary obligation agreement (locatio conductio). It happened because, in the case of locatio conductio rei (agreement to rent things, land in this case) the tenant was entitled only to short-term protection, which in some cases led to overexploitation of the farmlands.

The terrain leased under the ius in agro vectigali law belonged mostly to the state, communities, cities, colonies and even priests and vestals. They were often covered with fallow vegetation, mountainous or hard to cultivate, so a broad range of powers and the perpetuity of the lease were intended to encourage entering into this type of legal agreement. Such a lease was permanent (forever – in perpetuum), as long as the tenants and then their heirs regularly paid the agreed rent (vectigal). The tenants had the right to interdictal protection as well as actio in rem vectigalis (in case of losing the property).

In the eastern part of the Roman empire emphyteusis, which originated in Greek law and was similar in its construction, was common. It was a long-term or hereditary lease in which the tenant was obliged to pay a yearly rent (canon) and to cultivate the leased land. In the year 480 CE. Emperor Zeno proclaimed the creation of an emphyteutical contract, which was shaped by mixing both forms of the perpetual lease.

In order to enter the perpetual lease it was enough to have an informal agreement between the land owner and the tenant, the agreement could be also created on the base of the land owner’s last will. Such an agreement provided the tenant with both responsibilities and powers. Among the former was paying the rent to the land owner every year and covering all taxes related to the leased land. The tenant also had to keep the land in good condition. If he decided to sell the emphyteusis, he would have to inform the owner first and if he succeeded in selling it, there was an obligatory payment called laudemium (approximately 2% of the price) which he would pay to the land owner.

Among the powers of the tenant was the right to independently decide about any changes in terms of type of plants cultivated on the leased land and to keep the benefits created in the process of separatio (separation of benefits from the main thing – in this case mostly fruits and vegetables). He could decide to sell the emphyteusis as well as use all the available means protecting possession. The lease was void in the case of destruction of the land, if the emphyteusis and ownership belonged to the same person (when the owner used his right of first refusal – in this case no laudemium was paid) and if the tenant was removed after not having paid the rent for three consecutive years.

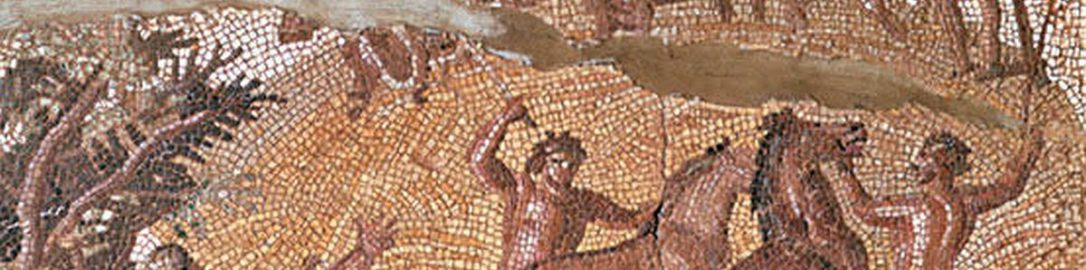

The perpetual lease became more and more popular as the empire expanded when more and more land belonged to fewer and fewer land owners. During the 3rd century CE, a time of an economic crisis, many lands could be classified as agri deserti (deserted lands), which were ideal as the objects of the perpetual lease. The emphyteusis was the beginning of creating feudal social relations, which became common in the middle ages.