Chapters

When the Visigoths conquered Rome in 410 CE, contemporaries thought that the end of the civilized world had come. In fact, Rome was no longer the capital of the Empire and was no longer as important as it used to be, but it was still a symbol of Roman civilization.

Background of events

The Goths were one of the Germanic tribes that pressed against the borders of the Roman Empire due to the “migration of peoples” initiated by the aggression of the warlike Huns. In 376 CE, the relegated Visigoths sought refuge within the borders of the Roman Empire. According to the Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus, the Goths were forced to leave their lands in Eastern Europe and look for new lands in the West. They decided that Thrace beyond the Danube is the best place to settle – the land is fertile and the river will provide a favourable position against the aggressive Huns.

The Goths were commanded by Fritigern and Alavivus. The two reached an agreement with the Roman Emperor Valens, ruling in the eastern prefecture of the Empire, and settled with the people in Moesia in exchange for the continued support of the Roman army with their troops. The Goths were given the title of foederati (“allies”), their army was to be incorporated as auxilia, and the Goths were to cultivate the land in Moesia and surrender to the fiscal system. In gratitude, Fritigern converted to Christianity. In order to secure the alliance and the loyalty of the Goths, Valens ordered them to donate a certain amount of wealth and young people and weapons.

The new arrivals, however, encouraged greedy Roman officials and tax collectors to take advantage of the situation. Life was deliberately made more difficult for the newcomers, valuables were demanded and access to food was made difficult. Roman authorities failed to deliver food for the Goths and aroused negative emotions. All valuables, and even wives and daughters, were forced to be handed over to private persons. The Goths, after months of constant humiliation, gave up obedience and decided to take matters into their own hands. The Roman-Gothic War (CE 376-378) ended with the great defeat at Adrianopleof Valens’ troops. It is believed that this was the greatest defeat of the Romans since the battle of Edessa in 260 CE, when Emperor Valerian was taken into Persian captivity. The Goths, after accepting them within the borders of the Empire, became an independent entity that over the next years actively participated in the destabilization of the Roman state.

Fritigern died in 382 CE without appointing a successor. It was not until around the 90s of the 4th century that Alaric was appointed the new king of the Visigoths, who began plundering expeditions into the eastern part of the Empire, leaving the lands given to the Goths for maintenance by the Romans. How complicated those times were is evidenced by the fact that in 394 CE Theodosius I, ruler in Constantinople, he made an alliance with the Goths and, with their support, undertook an expedition against the usurper in the west – Eugene. In the battle of Frigidus, the combined Roman-Gothic army defeated the enemy and Theodosius became an independent emperor ruling over the western and eastern territories of the Empire. In return for his services, Alaric was awarded the title of comes, which, however, the barbarian leader considered to be too low a position.

On January 17, 395 CE – after only one year of ties between the eastern and western parts – the able and combative Emperor Theodosius I died, who divided the Empire between his underage sons: the east was taken over by Arcadius and the west Honorius. The change in the situation in the Roman state encouraged Alaric to undertake further plundering expeditions. He decided that the previous agreement with the Romans had expired and he proceeded to invade Thrace, even reaching the walls of Constantinople. After negotiations, Alaric withdrew and went to Macedonia, plundering its lands and cities.

At that time, the only guarantor of the safety of the Empire was the outstanding Roman commander Stilicho, who was to be the guardian of young Honorius. However, the latter, taking advantage of the divisions in the Eastern Empire, also claimed the right to control the actions of Arcadius. Stilicho, relying largely on the allied barbarian troops, fought Alaric in the Balkan Peninsula. Despite many possibilities, Stilicho did not defeat the Goths, which is now explained in many ways, incl. as an attempt to control and weaken the Eastern Empire, or as a secret covenant with Alaric. Ultimately, Stilicho’s stance met with great criticism from the administration in Constantinople, and he himself was considered a public enemy.

At that time, Stilicho was forced to leave the Balkans and go to the areas under Honorius to deal with local matters. Then Alaric led his troops to Epirus, where he also conducted numerous plundering operations. Arkadius was forced to conclude an agreement with Alaric, who was awarded the title of magister militum per Illyricum in 398 CE. Thus, the Gothic commander received one of the most important military titles and the right to use goods in the Illyric province.

In the early fifth century CE, Alaric’s position in the east worsened, forcing him to seek new lands for his people. Taking advantage of Stilicho’s involvement in the fight against the Vandals and the Alans in Recia and Noricum, Alaric invaded Italy in 401 CE, occupying numerous towns and besieging Milan. Stilicho’s response was immediate – he returned to Italy and, at the head of his subordinate Vandals and Alans, forced the Goths to retreat. There were more clashes: at Polencja and Verona, which worsened the position of Alaric, who was forced to leave Italy and spread to Dalmatia. The siege of Milan terrified Honorius so much that he decided to move the capital to Ravenna, located on the Adriatic Sea. The city was surrounded by swamps and was seen to be easier to defend.

At that time, the alliances shifted again. Stilicho established cooperation with Alaric, thanks to which the Illyrian prefecture was under the control of the Western Empire.

In 407 CE, another wave of misfortune fell to the west – a rebellion under the leadership of Constantine III began in distant Britain; moreover, a massive invasion of Suebi and Alans passed through the Rhine and began to plunder Gaul. Taking advantage of Stilicho’s weakening/involvement, Alaric invaded Noricum and Pannonia. Moreover, he demanded 288,000 solidi and threatened to attack Italy. Stilicho, realizing the difficult situation, forced the payment of money from the Roman Senate.

In 408 CE, Emperor Arcadius died, and Stilicho, seeing his chance, left for Constantinople and offered to take care of his little son, Emperor Theodosius II. However, this was met with a definite refusal. Meanwhile, Honorius arrived at Ticinum, where Stilicho’s army was camped against Constantine. It was then that the imperial secretary Olympius (appointed to his position by Stilicho) caused the anti-German riots. Many of the highest dignitaries and friends of Stilicho were killed. Honorius himself supported the uprising and turned against Stilicho. The commander, who was then in Bologna, wanted to wait for the development of further events. As a result of the quarrel, part of the army departed from Stilicho, and one of the Gothic chieftains, Sarus, betrayed the chief and gave the order to kill him and his bodyguard, mostly Huns. The chief himself managed to escape with the remnants of his guard to Ravenna. There, Stilicho was deceitfully killed on August 22, 408. The death of the outstanding leader Stilicho was another step towards the fall of Rome.

First siege of Rome

After Stilicho’s death, Alaric, seeing his chance for easy loot, made an offer to Honorius: peace in exchange for hostages, gold and handing over Pannonia to his rule. The emperor’s refusal caused Alaric to undertake another expedition to Italy. Alaric’s forces won, among others Ariminum and headed south. In 408 CE, the first siege of Rome took place, a real nightmare for the Romans, who remembered the historic capture of Rome in 387 BCE. A panic ensued in the streets of Rome, which was exacerbated by the fact that barbarian armies took control of the Tiber and the city stopped receiving food supplies.

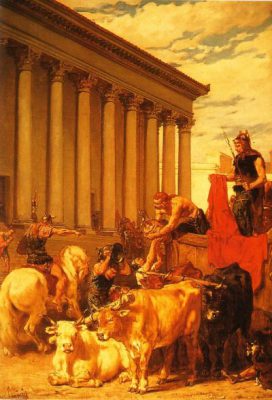

The Roman Senate decided to send emissaries to Alaric with the information that the people of Rome were trained in combat and were ready to fight. To this Alaric had to answer: “The densest grass is easier to cut than the rarest”1. When asked what are the conditions to withdraw from the siege; this demanded gold and silver and the release of slaves of barbaric origin. Then the envoys asked what he would leave for the Romans. To this Alaric replied, “Their lives”. Ultimately, a settlement was reached: Alaric was to receive 5,000 pounds of gold, 30,000 pounds of silver, 4,000 silk tunics, 3,000 scarlet-dyed skins, 3,000 pounds of pepper. Moreover, slaves ran away from the city, who in large numbers joined Alaric’s army, which at that time numbered 40,000 warriors. In order to fulfil their financial obligations, the inhabitants were forced to melt down valuable statues of ancient Roman deities, which was evidence of the fall of Roman power and values.

Second Siege of Rome

Honorius, unable to accept such humiliation, ordered five Roman legions to be brought from Dalmatia and deal with Alaric in Italy. In Etruria, however, there was a total pogrom of Roman troops, of which only 100 soldiers were to save themselves and flee to Rome. On top of everything else, Alaric was joined by his brother-in-law, Ataulf, who crossed the Alps, defeating Roman troops led by Olympius. Alaric again offered an agreement: he demanded Dalmatia, Noricum and Venice for his people. One of the Roman leaders – Jovius – suggested to the emperor Honorius that the title of Alaric magister utriusque militae should be given to the emperor, which was to reduce his demands. However, this was met with the refusal of the ruler.

During this time there were numerous negotiations and attempts to achieve the best possible position for both sides. News reached Alaric that Honorius wanted to recruit a detachment of 10,000 Huns, which made him decide to reduce the demands: for his people he only demanded Norikum without any tributes or titles. However, also this time the emperor refused.

A discouraged Alaric, in 409 CE, again besieged Rome and seized Portus, the principal port of the Western Empire. He also launched an attack towards Ravenna. Terrified Honorius looked for various ways of calming the situation; He was even getting ready to flee to Constantinople when 4,000 soldiers from the east turned up at the port of Ravenna.

Finally, it was decided to meet Honorius with Alaric 12 km from Ravenna. Alaric, while waiting for the emperor, was attacked by the Sarus unit – now allied with Honorius – the enemy of Ataulf, who, incidentally, once competed with Alaric for the Goths crown. Frustrated, Alaric gave up the meeting and set off for Rome again.

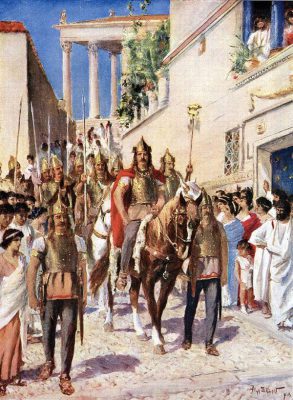

Third siege of Rome

After a brief siege at night, on August 24, 410, the Visigoths entered Rome through the gate Porta Salaria. The quick conquest of the city was due either to treason or the fact that the inhabitants were starving. The Goths p for three days plundered everything they could get their hands on. Roman slaves accompanied them. More important buildings were set on fire and plundered, including Mausoleum of Augustus, Hadrian, and the ashes of prominent Roman personalities inside them were scattered and desecrated. All movable goods were taken, including the precious ciborium (£ 2.025 silver) drinking vessel which was a gift from Constantine I. The buildings were destroyed, except around the old Roman curia and Porta Salaria. The Gardens of Sallustius burned down and were never rebuilt. The Basilica of Juli and the Basilica of Emilia were also destroyed. The Visigoths spared church buildings – two main basilicas: Peter and Paul (the Visigoths were Arians).

Many Romans were taken prisoner, including the half-sister of Emperor Honorius – Elia Galla Placidia, whom Alaric treated with all honours. The inhabitants of Rome were either killed or fled Rome and tried en masse to get to Africa or stayed in their homes. The people of Rome were tortured to reveal their hidden valuables. One such person was the 85-year-old Saint-Marcel a Roman, who, according to sources, was beaten by the Visigoths. The invaders did not believe the Roman woman was leading an ascetic life. As a result of the injuries, the woman died.

What is worth emphasizing, despite the tragedy of the situation, the siege was not too brutal by contemporary standards. Most of the buildings remained intact and the inhabitants avoided a general slaughter. What the barbarians were interested in were, first of all, all valuables that could be taken with you as loot. It is worth noting, however, that Rome as a city has significantly decreased its population. It is assumed that before the siege, the city had a population of about 800,000; after conquering the city, a large part of the population fled to Africa, Egypt and to the east, as a result of which in 419 CE it already numbered 500,000. Interestingly, some of the Roman refugees arriving in Africa were sold to lupanars by the local governor Heraclian, who wanted to enrich his treasure in this way. Interestingly, Heraclian was a faithful subordinate of Honorius, which only proves how difficult those times were and what a downfall of the then civilization.

It is also worth mentioning that when he heard about the “disappearance” of Rome, Honorius was supposed to understand that one of his chickens was missing, and he named it “Roma”2.

After conquering Rome

After three days of plunder, the Visigoths took their loot (Alaric was accompanied by Gallia Placidia, sister of Emperor Honorius) and marched south, looting i.e. Campania, Calabria, and threatening of an invasion of Sicily and a moving to North Africa; it was planned to settle in the fertile African lands. Alaric was aware that, having enormous grain resources, he could influence the emperor and force him to compromise, and play a significant political role in the Mediterranean. Ultimately, the plans were thwarted by a three-day storm in the Strait of Messina that destroyed the prepared fleet. His idea was later realized by Genseric, the leader of the Vandals.

In December 410, Alaric died and Ataulf took his place. According to legend, Alaric was buried in the riverbed of Busento, near the city of Cosenza (southern Italy), and with him all the property he had acquired in Italy. Throughout 411 CE, the Visigoths remained in Italy, plundering it completely and proving the weakness of the Roman state in the west.

The consequences for the inhabitants were also tragic. The invasion and destruction of the Goths in Italy increased taxes, and the aristocracy and the richer population ceased to support the maintenance of public buildings and to act pro publico bono.

Meaning

The followers of traditional Roman deities blamed the fall of Rome on Christianity, which, in their opinion, had caused God’s wrath. Massive accusations against Christianity caused the great Christian thinker of that time, Saint Augustine, to publish an enormous work in twenty-two books entitled De civitate Dei (“The City of God”). In it he referred to all the accusations, stressing that throughout its history Rome had to deal with cataclysms, and the pagan faith is extremely bizarre. What’s more, despite the fact that Rome was conquered, thanks to Christianity the Romans can feel victorious, because Rome is the City of God that will finally triumph. Augustine clearly distinguished Rome as an earthly city from the City of God.

It should be noted that the capture of Rome meant not only material losses but also spiritual losses, which were much more tragic. The sacking of Rome was a great shock to the people of Italy, convinced of the city’s power. A word of two words circulated throughout the Empire: Roma capta (“Rome sacked”). The last time Rome was conquered and plundered almost eight hundred years earlier. This was done by the Gauls in 387 BCE, led by Brennus, who, however, rivalled the then-still-small town. During this time, Rome became the capital of the Mediterranean world and the cradle of Roman statehood. Upon the news of the plunder of the “Eternal City”, Saint Jerome cried out despairingly: Rome, once the capital of the world, is now the grave of the Roman people”3.