Chapters

Battle of Adrianople (378 CE) was the clash between the Visigothic leader Fritigern and the Eastern Roman emperor Valens, who died during the battle.

Background of events

In 376 CE, Visigoths, being pushed back as a result of “the great migration of peoples” sought refuge within the borders of the Roman Empire. According to the Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus, the Goths were forced to leave their lands in Eastern Europe for the Huns and look for new lands in the west. They decided that Thrace beyond the Danube is the best place to settle – the land is fertile and the river will provide a favourable position against the aggressive Huns.

Goths were commanded by Fritigern and Alavivus. The two reached an agreement with the Roman Emperor Valens, ruling in the eastern prefecture of the Empire, and settled with the people in Moesia in exchange for the continued support of the Roman army with their troops. The Goths were given the title of foederati (“allies”), their army was to be incorporated as auxilia, and the Goths were to cultivate land in Moesia and surrender to the fiscal system. In gratitude, Fritigern converted to Christianity. In order to secure the alliance and the loyalty of the Goths, Valens ordered them to donate a certain amount of wealth and young people and weapons.

The alliance seemed to be a beneficial solution. From the point of view of the Romans, the Goths offered military support, greater income to the state and, in the long run, food supplies. In return, the Goths received land for cultivation and security guaranteed by the Empire. An effective alliance could guarantee stabilization in the region for many years. By order of the emperor, numerous transport units were delivered for the Goths to migrate effectively. However, as Ammianus Marcellinus recalls, the Goths did not follow the instructions and crossed the river en masse, which led to numerous drownings and chaos. According to Edward Gibbon, finally almost a million Goths, including 200,000 warriors, settled in Moesia. By comparison, Eunapius, a 4th-century Greek writer, gives the figure of 200,000, including civilians.

However, aside from the exact numbers, surely a great number of barbarians soon appeared within the Roman borders. The new arrivals, however, encouraged greedy Roman officials and tax collectors to take advantage of the situation. Life was deliberately made more difficult for the newcomers, valuables were demanded and access to food was made difficult. Roman authorities failed to deliver food for the Goths and aroused negative emotions. All valuables, and even wives and daughters, were forced to be handed over to private persons. The Goths, despite numerous evidence of ill-treatment by the Romans, avoided open combat. Envoys were sent to the emperor with requests for good treatment and fulfilment of obligations. Here, especially the Roman leaders from these areas should be negatively mentioned: Maximus and General Lupicinius.

Realizing that the Gothic camp on the Danube had become hostile to Roman authorities, it was decided to disperse the Goths across the provinces. Their leaders in turn – Fritigern – were ordered to march to Marcianopolis. Lupicinius, a Roman commander in Thrace who himself played a significant role in the exploitation and intolerable actions against the Goths, invited their chief leaders to a sumptuous feast to either murder them or reconcile them. During the meeting, however, the main group of Goths, who had been ordered to camp outside the city in an attempt to get some provisions, got into a chaotic fight with the Roman garrison, which refused to enter them. As soon as the sounds of fighting reached Fritigern, he, along with the rest of the Goths, returned to the gothic camp outside the city and declared war.

The clash took place about 9 km from the city of Marcianopolis. The almost 5000 group of Roman veterans fought bravely, but the cowardice of Lupicinius1, who escaped from the battlefield and the numerical superiority of the Goths led to the victory of the barbarians who took over the weapons of the fallen Romans.

The events in Marcianopolis shattered the faith of the barbarians in the possibility of peaceful coexistence within the Empire with the Romans. Months of exploitation of the barbarian people by greedy officials and fiscal collectors led to the idea of creating an independent Gothic state. Ammianus Marcellinus blames the outbreak of the Roman-Gothic war (376-378 CE) entirely on the Romans2.

Over the next two years, the Goths plundered and strengthened their position on the Balkan Peninsula. There were further smaller clashes with Roman troops, which, however, ended with the victories of the barbarians. In 378 CE, Emperor Valens decided to finally deal with the arbitrariness of the Goths. To this end, he brought in more troops from Syria and made arrangements with the emperor of the west, Gratian, to support him with Gallic troops.

Valens left Antioch and went to Constantinople on May 30, 378 CE. He ordered his leader Sebastian to reorganize the Roman troops in Thrace. There were several Roman-Gothic clashes, where especially the Romans were very successful. Valens, confident of his troops and aware that Gratian had won a great victory over the Alamans who had invaded Roman territories through the Rhine, decided to face the enemy on his own. Hungry for glory, he marched with the army from Melantias to Adrianople (now Edirne in the European part of Turkey), where he joined forces with Sebastian. On August 6, the emperor was informed by a reconnaissance that about 10,000 Goths were marching from the north towards Adrianople. The Roman army swiftly reached the city and fortified itself well.

At that time, an envoy of Gratian came to the Roman camp, who insisted that Valens wait for his support. Some of his troops were in Sirmium in Pannonia, and it took some more time to get there. Most of the leaders supported the idea; however, Valens felt that the conflict should be settled as soon as possible. In addition, his confidence was strengthened by Fritigern’s proposal for peace and alliance in exchange for some territorial concessions by the Romans.

Army

Roman army

We don’t have much information about which troops Valens’ army consisted of. One of the few historical sources on this period is Roman History by Ammianus Marcellinus, in which the Roman historian focuses on the description of the battle, mentioning only a few units.

Valens certainly had battle-hardened troops. The army consisted of seven heavily thinned legions (including the 1st Maximilian Legion), auxilia troops and cavalry made by archers (sagittarii) and the elite cavalry scholae. There was also a detachment of Arab horsemen in the army, who were mainly used for quick engagements.

Today, historians believe that Valens’ army could have counted 15,000 (10,000 infantry and 5,000 cavalry).

Gothic army

The army of the Goths consisted mostly of heavy infantry supported by cavalry, which played a major role during the Battle of Adrianople. Ammianus Marcellinus reports that the Romans recognized the Gothic forces at 10,000 men, which was a big mistake because part of the army was still far from the place of the battle.

Today, researchers say that the Goths’ forces could count from 12 to 15 thousand warriors.

Battle

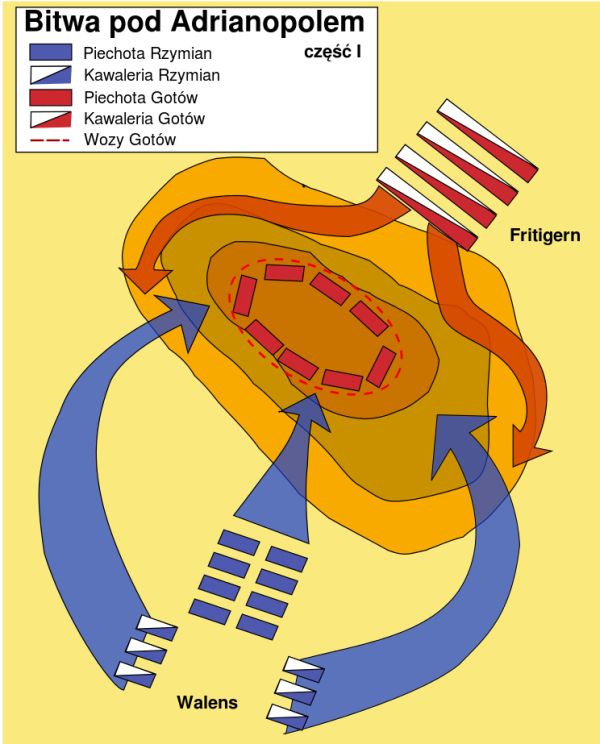

On August 9, 378, Valens’ army, having left in Adrianople its rolling stock, treasury, administration and all unnecessary defence equipment, set out north of the city. They marched about 12 km in rough terrain to reach a hill in the middle of the day, on top of which was the Goth camp, made up of linked carts. The Romans were exhausted by the intense march, which certainly also influenced their availability in the subsequent battle.

The Romans decided that the camp constituted the entire Gothic army, under the command of Fritigern. As it turned out, there were infantry and part of the cavalry within the camp, but the main part of the cavalry, under the command of Ostrogoth Alateus and Alan Safraks, headed towards the camp.

Roman troops lined up in line formation, with Trajan’s heavy infantry and support units inside and cavalry defending the flank. Valens and his bodyguards were behind the infantry. Fritigern tried at all costs to delay the attack of the Romans by negotiating the exchange of prisoners and expecting his main part of the cavalry.

At one point, without an order from the command, Bacurio of Iberia set out at the head of his cavalry towards the Visigothic camp, while the rest of the Roman infantry remained in their positions. The reaction of the Romans was largely due to the anger at the Goths for destroying and burning their lands for two years. The ride on the left flank followed suit, hoping to attack the Goths from the side and take advantage of the surprise effect. The Roman attack was repulsed without difficulty, however, as Alateus and Saphrax returned in time. The Roman soldiers on the left flank rushed to flee.

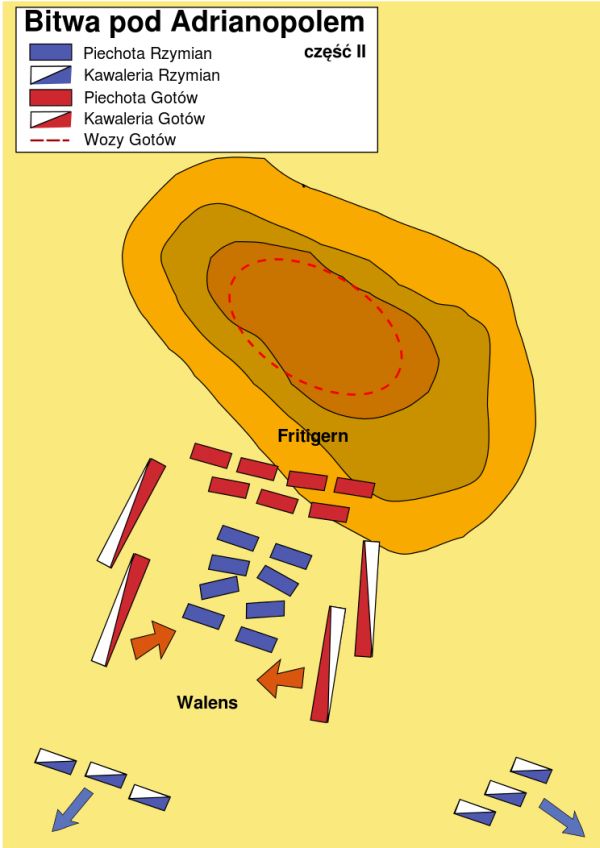

The Goths took control of the battlefield and, approaching the mainline of Roman troops, began shelling the Romans, then carried out an infantry charge. While the infantry and the right flank were battling the Goths, the cavalry from the Roman left flank turned and attacked Alateus and Sapphraks again. Such a twist caused the enemy to be completely by surprise, thanks to which the Romans forced the Goths to withdraw and reached the enemy’s carts. It is assumed that this was the turning point of the battle – if at this point the Roman cavalry received the support of additional Gratian units, perhaps the barbarians could be forced to flee.

With time, however, the Roman cavalry lost its momentum and the difference in the number of soldiers became obvious. The Roman cavalry escaped again, and the Roman infantry was surrounded. Disciplined legionaries began to fight for their lives in the encirclement, which over time led to a chaotic escape and attempts to break through the enemy troops. There was a real slaughter of Roman troops, which were pursued by the Gothic cavalry.

In the battle or shortly afterwards, Valens himself was killed – the first Roman ruler to die in the battle. There are many different versions of the description of the last moments of Valens’ life. One of them says that Valens died from an enemy arrow as he fought alongside his men surrounded by an enemy. According to another version, the emperor was supposed to take refuge in a nearby building with the help of his commanders, which was set on fire by the Goths. Regardless of the version of the events, however, the emperor’s body was not found and he was pronounced dead.

Consequences

About a third of the Roman army managed to successfully withdraw. The losses, however, were enormous. Apart from the emperor himself, a wide range of officers, including General Sebastian, died. The Roman elite from the eastern territories and the core of the army were destroyed. The lack of recruits and volunteers later caused significant problems in the reorganization of the army in the east, which made the army more willing to use the services of barbarians.

After the victorious battle of Adrianople, the furious Fritigern, at the head of the victorious Gothic troops, tried to capture the city of Adrianople. Ammianus reports how many Roman soldiers who escaped from the battlefield were not allowed into the city walls and had to fight the Goths in the open. Then Fritigern devastated the Danube provinces and Greece, reaching Constantinople, whose massive fortifications effectively discouraged the barbarians from being besieged.

It is believed that this was the greatest defeat of the Romans since the Battle of Edessa in 260 CE when Emperor Valerian was taken into Persian captivity. The Goths, after accepting them within the borders of the Empire, became an independent entity that over the next years actively participated in the destabilization of the Roman state. He was involved in political games, once as an ally, sometimes as an opponent of the Romans.

The defeat of the Romans at Adrianople is often considered a turning point in the history of Rome when the Roman state began to decline.