Chapters

Claudius Ptolemy (Claudius Ptolemaeus) was born around 100 CE. He was a Greek astronomer, mathematician and geographer. He lived in Egypt, which at that time belonged to the Roman Empire.

We don’t know much about his life. According to Theodor Meliteniotes, a Byzantine astronomer who lived a thousand years later, Ptolemy was to be born in Ptolemais Hermiou in Tebaida, Upper Egypt, but there is no evidence of this. From the observations of the planetary system contained in Almagesta, one can deduce the author’s approximate time of activity. The earliest date resulting from the described constellation is March 26, 127 CE, and the latest is February 2, 141 CE, which means that the creation of the treaty falls on the years of the rule of the emperors of the Antonin dynasties Hadrian and Antoninus Pius, and the life of Ptolemy himself can be dated to the first three quarters of 2nd century CE.

His name Claudius testifies that he possessed Roman citizenship probably inherited from the ancestors of Claudius or Nero’s Caesars. The nickname Ptolemy, on the other hand, informs us that he was of Greek descent, or that his ancestors were Hellenized inhabitants of one of the eastern monarchies formed after the death of Alexander the Great.

In Almagesta he refers several times to Teon of Smyrna, who was to give him his own observations of the sky between 127 and 132 CE and he could be his teacher. From his work we learn that in the field of philosophy he recognized Aristotle, was familiar with the work of the mathematician Menelaus of Alexandria, the astronomers Hipparchos of Nike and Poseidonios of Rhodes, and the geographer Marinos of Tire.

Ptolemy is credited with the authorship of the epigram:

I know that I am mortal by nature and ephemeral,

but when I trace at my pleasure the windings to and fro of the heavenly bodies,

I no longer touch earth with my feet. I stand in the presence of Zeus himself and

take my fill of ambrosia.

Astronomy

Ptolemy was a zealous follower of astrological doctrines. He expressed this by linking periods of human life to seven planets. The division discussed below is not the only one known by antiquity, but it is one of the most interesting. Here is the abbreviation for his treatise:

For the first four years, the child is under the influence of the moon. He often changes his face and quickly runs through the zodiac signs, attracting humid fumes of the Earth. Therefore, this child is constantly changing, growing in the eyes, needs moist food; its members are not fully educated, and their minds are immature. All this corresponds to the unstable, shaky lunar forces.

Mercury reigns over the second period from five to fourteen years of age. He forms a physical and spiritual skeleton in the child, sows seeds of knowledge, stimulates and develops the young mind, brings out individual inclinations.

The third period, from fifteen to twenty-two, belongs to the planet Venus. This is associated with violent sexual arousal, a tendency to love without choice, succumbing to passion, blind momentum.

The fourth and first period of male life covers nineteen years, from twenty-third to forty-first. It is like a sunny peak of human existence and the Sun shines on it. He develops a passion for independent life, hunger for fame and meaning, but also a desire to establish his existence on solid foundations. The real man finally turns away from the silly, noisy and ignorant of playfulness of the flashy youth, repels all her jesting.

But the other half of male life, forty-two to fifty-six years old, are influenced by the evil planet Mars. It brings a lot of bitterness, a lot of spiritual and bodily concerns. And also a painful reflection that the most beautiful period is over. This, however, stimulates a real man to do something before the inevitable end.

And here is the reward: the second life peak, and the first period of old age, fifty-seven – sixty-eight years. The planet Jupiter rules then. It relieves brutality and anxiety, discourages from excessive efforts, gives forgiveness, cheerfulness the ability to support others with mature and kind advice.

And finally, the second period of old age, the zone of influence of the weakest and slowest of the planets – Saturn. So gradually the vital forces of body and soul wither1.– Aleksander Krawczuk, Starożytność odległa i bliska, Warszawa 1980

Ptolemy rightly believed that the motions of celestial bodies can be described using mathematical formulas, so he gave his title astronomy the title Mathematike Syntaxis (“Mathematical Structures”). The name Almagest used today, originated from the Greek word megiste (“the largest”), which the Greeks quickly began to describe it. The treatise summarizes the achievements of Greek astronomy from the time of Eudoxos of Knidos (4th century BCE) and his model of the celestial spheres, through Hipparchos of Nikkei, to Ptolemy himself. Hipparchos’ geocentric theory based on deferent, epicycle and eccentric was included and corrected in Almagesta.

In the geocentric model, Earth was the center for eight concentric spheres with planets, the Sun, the Moon and stars on them. The planets also moved around small circles called epicycles. The main advantage of this concept was that the seemingly chaotic movements of celestial bodies so far could be calculated, and their location with fairly high accuracy predicted. Ptolemy was aware of his flaws. The moon in his model moved so much that when seen from Earth it would have to be twice as large. It remains a mystery whether his author believed in his vision of the Universe, or whether the solution he proposed was to have a more practical purpose, i.e. to enable accurate measurements of predicted positions for celestial bodies.

Interestingly, Ptolemy was also interested in astrology. He dedicated his next work to Apotelesmatiká (“Astrological Influence”), also known as Tetrabiblos (“Quadruple”). For Ptolemy this treaty was a natural continuation of Almageste. He defends astrology against accusations and tries to prove that, although in his opinion the influence of celestial bodies is purely physical, it has a significant impact on our actions. Although without mathematical accuracy, it is possible to predict the future based on observations of the sky.

In Procheiroi Kanones (“Handy Boards”) an ordered set of astronomical tables is presented, with an introduction explaining the rules of their use.

Geography

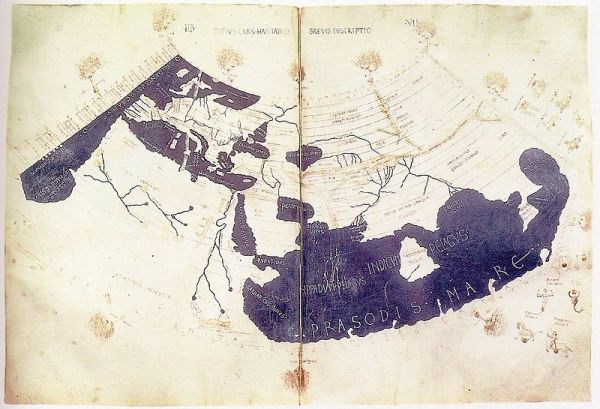

Ptolemy treated geography as a science of presenting the Earth with a drawing. However, thanks to his astronomical preparation he gave it a mathematical dimension. He was familiar with the sphericity of the Earth and he used his maps to project the surface of the ball onto a plane. He accepted, however, after Poseidonios of Rhodes, an erroneous calculation of the length of the geographical degree, which did not avoid considerable inaccuracies in his work. The Ptolemaic definition of latitude is still valid today.

Geography (Geographike Hyphegesis – “Introduction to Charting”), also known as “Geographical Science”, was an attempt to create the most accurate map of the world he knew. It consists of eight books. The first is the theoretical introduction, aimed at, if necessary, enabling the reader to reconstruct the plans independently. Books from II to VII contain the names of places and characteristic geographical points (about 8000 toponyms) with coordinates. What interesting in Book II describing, among others lands from the Danube to the Baltic Sea, the author mentioned Budorgis later identified with Brzeg, Kalisia identified with Kalisz, Karrodunon connected with Kraków or Askaukalis identified with Bydgoszcz. In Book VIII there is a list of the most important cities with more precise coordinates. 26 maps were attached to the books.

He also dealt with optics and music. The treatise – Optics – in five books has not survived to our times in the original. Music historians, in turn, appreciate Ptolemy’s Harmonics as the pinnacle of ancient music theory and one of the few rich sources of knowledge about it.

He died around 168 CE probably in Alexandria.