The Roman games involved vast numbers of animals. Some animals were performers. Elephants balanced on ropes, bowed to the emperor and traced out words with their trunks. Lions gummed their trainers’ hands and played fetch with live hares. Monkeys dressed as soldiers rode goats around the arena.

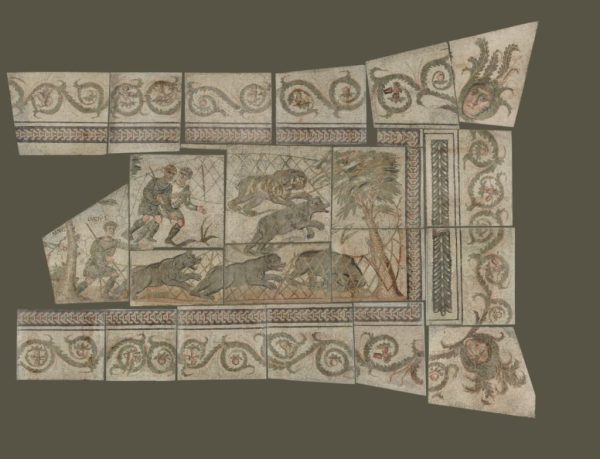

Other animals were executioners. Leopards were unleashed on criminals bound to stakes. Condemned men dressed as Icarus were dropped into cages of bears. Christians were thrown to the lions. Most of the animals that appeared in Roman arenas, however, were there to be hunted. One of Rome’s four gladiatorial schools was dedicated to training venatores or bestiarii, the hunters of the arena. Armed with a javelin or bow, one of these men could easily bring down dozens of deer, gazelles, or any other herbivore. Especially bold hunters learned to stun bears by punching them in the face and to blind pouncing lions with their cloaks. A few were skilled enough to kill an elephant with a hunting spear.

No fewer than 9,000 animals were killed during the dedicatory games of the Colosseum. A generation later, during the 123 days of games celebrating the conquest of Dacia (modern Romania), 11,000 were slaughtered. Although these celebrations were exceptional, the demand for exotic animals was constant. Over the seven centuries in which beast hunts were staged, literally hundreds of thousands of animals must have been imported into the Empire’s arenas.

Some arena animals, like boars, deer, and wolves, could be found in Italy. But most were more exotic. Bears were shipped from as far away as Scotland. From northern Europe came elk, bison, and the fierce aurochs, a now-extinct species of wild cow. Tigers were taken in northern Iran and India. Egypt produced crocodiles and hippos. Other parts of North Africa provided lions, leopards, panthers, hyenas, and elephants. Sub-Saharan Africa sent gazelles, giraffes, ostriches, zebras, apes, and the occasional rhinoceros.

The process of capture and transport began a year or more before the games, when the emperor instructed his provincial governors to begin hunting animals. If soldiers were stationed in their provinces, these governors would have detachments of troops sent out. We have evidence for Roman soldiers netting gazelles in Egypt, stalking lions in Algeria, and bagging bears and bison in Bulgaria. A few soldiers, in fact, became semi-professionals and received titles like ursarius – bear hunter. One of these men, a centurion on the German frontier, managed to capture 50 bears in six months. In addition to arranging beast-catching patrols, governors would contact local groups of professional hunters. In parts of Roman Africa, these men were organized into sophisticated guilds. Elsewhere, they were probably freelancers, contracted to provide a certain number of animals by a given date.

The Romans had many methods of trapping animals alive. Some herbivores were lassoed by cowboys on fast horses. Others were frightened into long nets. Bison, which could charge through any net, were funnelled into valleys lined with greased hides, where they would lose their footing and roll into an enclosure. Elephants, likewise, were chased into closed valleys or immobilized in deep holes.

Big cats were taken in pit traps. A hole would be dug, and surrounded by a low wooden fence. A pillar would be left in the pit’s centre, and something cute and fluffy tethered to the pillar’s top. If the target was a lion, baby goats or lambs were the best bait. Leopards preferred puppies. When the lion or leopard leapt the fence to devour the bait, it would plummet into the pit. An alternate method of taking big cats involved teams of armoured horsemen with torches, who would chase them into netted enclosures. Leopards, supposedly, could be also captured by dumping wine into their watering-holes and letting them drink themselves into a stupor.

Tigers were typically captured young. Hunters, we are told, would steal a female tiger’s cubs from her den and gallop off with them. When she realized her cubs were gone, the tigress would pursue the hunter. But just as she caught up with him, he would drop one of her cubs. The tigress would stop to rescue it, and bring it back to her den. Then she would resume her chase. Just as she got close enough to pounce, the hunter would drop another cub, and she would stop again. By the time she returned, the hunter would be safely out of reach with the remaining cub or cubs. In a variation of this technique, a hunter would drop a mirror instead of a cub as the tigress approached. Mistaking her reflection for one of her cubs, she would stop and worry the mirror while the hunter escaped. Or so it was said.

I go into more detail on how animals were captured and transported to the arena in this video: