In 43 BCE a private agreement between three men sealed the fate of the Roman republic. Even before the death of Julius Caesar, the Roman republic was dying out – torn apart by the ambitions of successive great leaders and the civil wars they caused. But after the Ides of March, her agony accelerated rapidly. But formally it still continued – consuls and other officials were still elected, and the Senate continued its sessions. People’s assemblies were then convened…

Everything changed in the fall of 43 BCE. Three ambitious and powerful men reached an agreement ending the rivalry between them. They were Octavian, Mark Antony and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus – they had almost everything in common, but had only two things in common – each aspired to some extent to be the heir of Julius Caesar and they had a common enemy – supporters of the republic. Thanks to the agreement concluded at that time, the united “Caesarians” were able to devote their strength and resources to the fight against Caesar’s assassins. This “gang of three” called themselves “triumvirs”, or more loftily: “three men for for organizing the state” (Tres Viri Rei Publicae Constituendae). There is some irony in this, considering how events unfolded next.

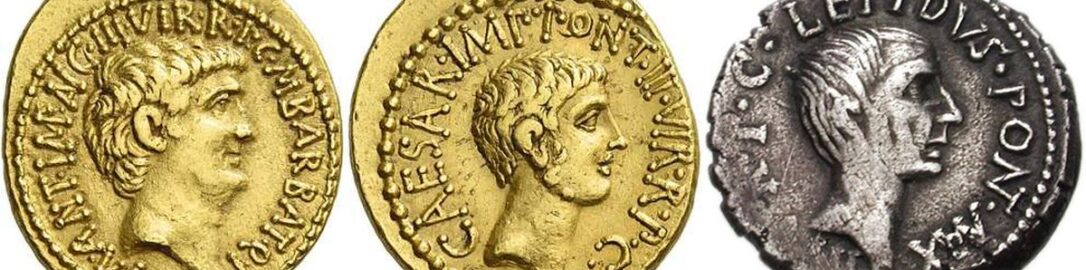

Let’s take a look at these three:

- Mark Antony – the most experienced, towered in authority over the others.

- Oktawian – the youngest, but the most ambitious. He had little to lose, but much to gain. Uncompromising, cynical and painfully ruthless.

- Lepidus – the least important member of the triumvirate. No charisma, no political support, unambitious.

The very circumstances of concluding the agreement are surprising – it is not an official agreement concluded publicly and with the authority of the state. Contrary! They hated each other and distrusted each other so much that in order to conclude an agreement, they had to meet on neutral ground – a small river island – completely alone, without any guards. But the troops loyal to them were stationed so close that in the event of a trick, they were ready to jump into battle at any moment to save the negotiating triumvirs.

Let us now take a moment to look at the agreement they concluded, because it was truly surprising – it had no constitutional basis, it was an ordinary contract. But under it the triumvirs essentially placed themselves above the law. They agreed among themselves that all decisions of other state bodies – including the senate, consuls, praetors, etc. – must be consistent with the decisions of the triumvirs. They divided state territories and spheres of influence among themselves, and decided in advance who would hold which offices in the future (without the electoral procedure…). In other words, although republican institutions persisted, the private compact of the triumvirs elevated them above the law and official authorities. From now on, all important decisions were to be made between the triumvirs, and other bodies were only to support them with their authority so that the legal requirements of the republic were met.

It is interesting what the further fate of the triumvirs was. The agreement was creaking at the seams and causing conflict almost from the very beginning. They were united primarily by a common enemy, but when he was defeated in the Battle of Philippi, the dissolution of the triumvirate was only a matter of time. Lepidus, deprived of charisma and political support, was the first to be marginalized and quickly became only an “appetizer” for the other two triumvirs. Octavian and Antony were soon divided by another civil war, which was unexpectedly lost by the older and more respected Antony. Octavian, the future emperor and sole ruler, remained on the battlefield.

Although the triumvir agreement did not stand the test of time, it set a dangerous precedent. It showed that someone else could be placed above the official state institutions – someone who had the power to force his decisions on the institutions. From that moment on, official titles slowly became mere decorations, honorary decorations in the biography of the people who held them. Real power passed first to the triumvirs and then to the emperors. This is how the republic died.