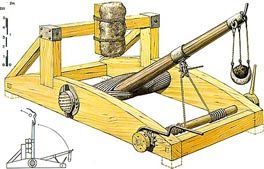

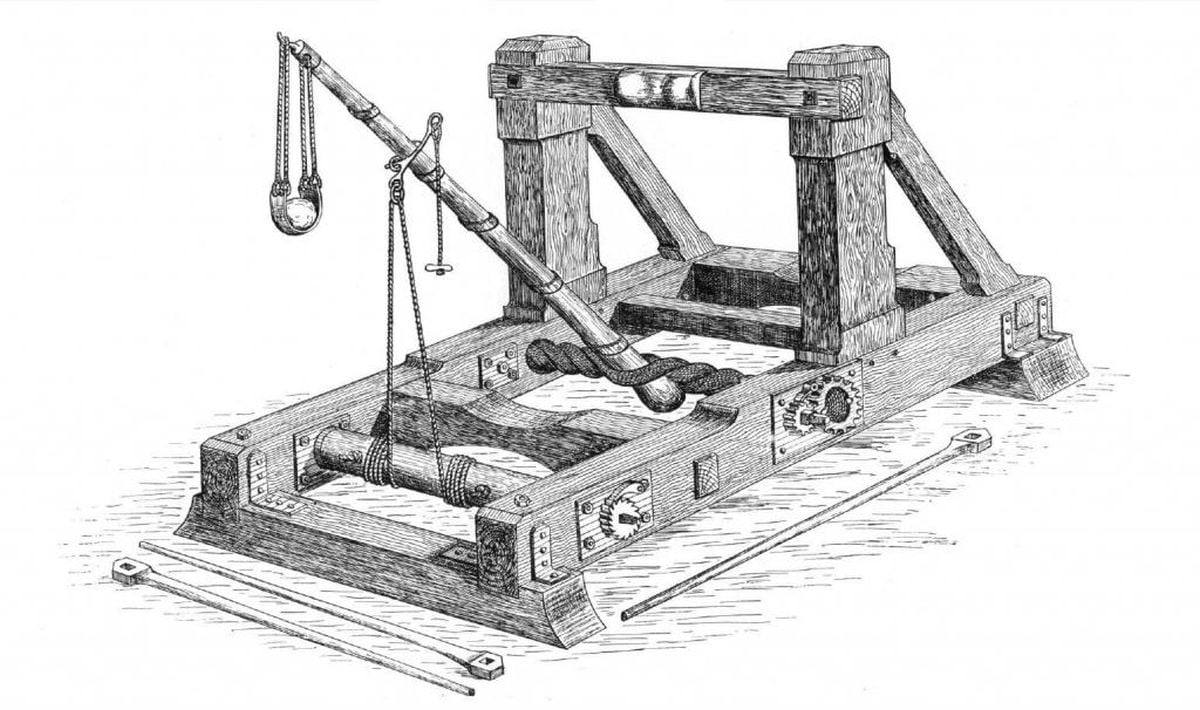

Onager (also mangonel) was a kind of war machine used in antiquity, especially in the Roman army. Equipped with a “spoon” on a rigid arm, was able to throw stone missiles and burning logs over a long distance. Catapult was built on a skid chassis.

Onager should probably be identified with the monancone (Greek siege weapon). The invention of the latter is attributed to Philo of Byzantium around 210 BCE (Eric William Marsden). It is worth adding that Philo also invented the first thermometer. According to other sources, onager was invented in Greece in the year 385 BCE by the mechanic Ammianus Marcellinus (Robert M. Jurga).

A powerful jerk and a machine lift at every shot, Romans called “a kick of a wild donkey”, hence the later name of the machine, onager or donkey.

Due to the appearance of onagers, Ammianus Marcellinus also calls them scorpions. This has nothing to do with machines bearing the same name. In turn, Marcellinus describes the correct construction of the machine:

Between two posts a long, strong iron bar is fastened, and projects like a great ruler; from its smooth, rounded surface, which in the middle is highly polished, a squared staff extends to a considerable distance, hollowed out along its length with a narrow groove, and bound there with a great number of twisted cords. To this two wooden rollers are very firmly attached, and near one of them stands the gunner who aims the shot. He carefully places in the groove of the projecting iron bar a wooden arrow, tipped with a great iron point. When this is done, strong young men on both sides quickly turn the rollers and the cords. When its point has reached the outermost ropes, the arrow, driven by the power within, flies from the ballista out of sight, sometimes emitting sparks because of the excessive heat. And if often happens that before the weapon is seen, the pain of a mortal wound makes itself felt.

– Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae, XXIII, 4, 2-3

For a change Vitruvio mentions the principles that must be followed when building these siege engines:

All these proportions are appropriate; some, however, add to them, and some diminish them; for if the capitals are higher than the width, in which case they are called anatona, the arms are shortened: so that the tone being weakened by the height of the capital, the shortness of the arm may make the stroke more powerful. If the height of the capital be less, in which case it is called catatonum, the arms must be longer, that they may be the more easily drawn to, on account of the greater purchase; for as a lever four feet long raises a weight by the assistance of four men, if it be eight feet long, two men will raise the weight; in like manner arms that are longer are more easily drawn to than those that are shorter.

– Vitruvius, De architectura, X.10.6

In the period of the increased expansion of the Romans, the machine was improved. At that time, precise rules for constructing catapults were developed, strictly observing the mutual proportions of their individual elements, based on the results of experiments.

Onager had a chassis with wheels and a long arm with a container for stones, pieces of lead or tar. The energy needed for the shot came from twisting elastic horizontal ropes, made of hair or veins of animal origin, between which one of the ends of the propelling arm was placed. In order to fire a projectile, the arm was pulled back, almost to a horizontal position and attached to a rope that acted as a trigger. Then a stone was placed in the container, the arm was released, which projected the projectile, stopping on the beam fixed in the centre.

The accuracy of catapults was amazing, and thrown-out stones weighing 30 kg flew even up to 1100 meters when 50 kg to 450 meters.

Artillerymen were distinguished by excellent sight and accuracy. They were specially trained, and their skills were first trained in archery, then ballistic, and finally catapults. In this way, they improved their accuracy to an extremely high degree.

Onagers were also often used to throw away human excrement and the heads of dead prisoners, which would cause a plague in the besieged city and reduce the morale of the defenders. Some onagers had special containers that could fire special projectiles. Such missiles were called sige and some weighed over 1 ton.

In the Roman army, every century had 1 onager, cohort 5, and a legion of as many as 50. During the time of Julius Caesar, their number was doubled and placed in a field, usually in front of the infantry line, between the first cohorts. The servicing of the machines was from 2 to 8 people, and it was transported in a form spread over 4 wagons hauled by oxen.