Chapters

Clothing in ancient Rome owed a lot to the Greeks, but it should be emphasized that Romans created their own style of clothing (you can say more sophisticated). The material used to create clothes was either wool or (to some extent available) linen. Clothes were sewn with the help of thick and bulky needles that certainly would not meet today’s standards. All seams and stitching were kept to a minimum. There were no buttons on the clothes, but various types of brooches or snaps were used.

Underwear

As underwear, the Romans wore a simple hip covering, tied on both sides. Roman lingerie had several terms, which was probably due to the many shapes and forms of clothing. It was defined as: subligar, subligaculum, campestre, licium or cinctus. Women wore simple bras in the form of a tight and tightly tied bust material (fascia pectoralis – under clothing, mamillare or subligar) and under the bust and on clothing (strophium, mamillare, cingulum). They wore a loincloth subligaculum on their hips. Over time, lingerie fashion has developed in a style similar to our contemporary bikinis costumes. This is evidenced by the floor mosaics created at the end of the 3rd century CE in Villa Romana del Casale in Sicily.

Men’s underwear was no simpler. Initially, only a linen loincloth was worn under the gown – the subligaculum mentioned. Later, femoralia began to be worn, a form of knee-length canvas pants modelled on German slave costumes. Linen was supposed to be made of linen, whereas Spanish, Syrian and Egyptian types were of exceptional quality.

Roman soldiers also put on some form of leather bands for intimate places. Some were wedge-shaped, which made them look like our modern panties. The evidence of this dress is the finds of archaeologists in the military camp Vindolanda in northern England. Gladiators fighting in the arena also wore such armbands.

Tunic

The dress of the Romans consisted of a tunic and an outer garment (toga). The citizen’s tunic was white or cream-coloured natural wool, while senators and equites wore tunics decorated with stripes (clavus). The tunic corresponded to the Greek chiton. Distinctions occurred between states. This was manifested in the fact that the equites had two purple stripes going from shoulder to waist (tunica angusticlavia), while senators, one wide walking in the middle, from the neck (tunica laticlavia). A separate tunic, with embroidered palm leaves (tunica palmata) was reserved for the winner.

For the poorest, slaves and children, the tunic was the only cover. The tunic worn by plebs, craftsmen, merchants and labourers often had no sleeves. As a rule, she was girded with a rope, often fastened on only one shoulder, which was a cheap and practical cover (two parts of the material sewn on the sides and on the shoulders with a hole for the head).

The tunic was worn primarily at home, while every exit to the streets required an additional robe – a toga.

2) Tunica angusticlavia was worn by equites and higher classes. It had two purple narrow stripes (angustus clavus) on the back and front about 4cm wide.

3) Tunica laticlavia was a senatorial tunic with one wide belt (latus clavi), about 8cm wide. Senators wore tunics that were slightly longer and not fitted.

There was still tunica palmata, with embroidered palm leaves, which was reserved for the triumphant and worn along with the picta gown. She was purple.

A richer form of a tunic, formed during the late Empire, was dalmatica, woollen, linen or linen; with one-piece wide sleeves. Next to her, the Romans also wore a sleeveless tunic (colobium). In the 3rd century AD, the Romans began using a long-sleeved tunic (tunica manicata). Putting on such a garment before this period was considered a manifestation of effeminacy. A similar effect was caused by putting on a very long tunic and falling to the feet (tunica talaris).

Usually, one tunic was worn, but from the third century BCE, a second one was started (tunica interior or subucula). During the winter, during the cold season, several tunics were put on. For the poorest, slaves and children, the tunic was the only cover.

The tunic was worn primarily at home, while every exit to the streets required an additional robe, called a toga. The gown was made of white, woollen material, about 3 meters wide and 6 meters long.

Toga

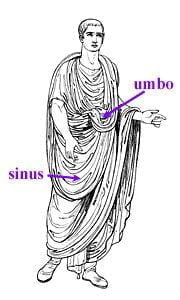

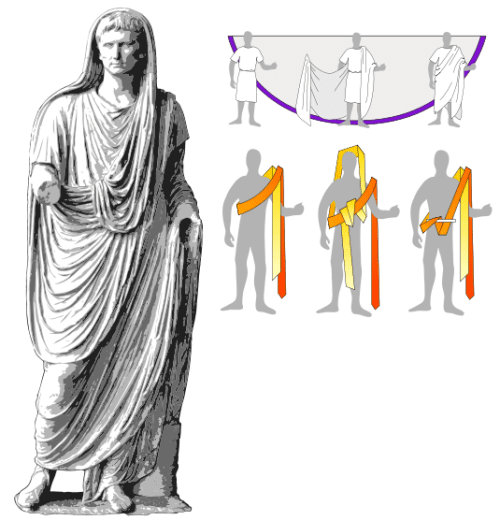

The earliest gown is dated to the late republic. It was relatively simple and was called toga exigua. During the golden age, the gown was enriched with sine, a pocket for all sorts of small items and an additional umbo pocket. For religious ceremonies, priests from the back of the toga formed a hood.

Toga was a sign of belonging to a particular social layer. The simplest toga type was toga virilis, also called toga pura or toga libera, made of plain white wool. Candidates for public offices founded toga candida. A separate type of gown was also available on the first day of office when the praetexta gown was worn, decorated with a purple stripe of varying width.

Boys who had not yet reached the age of majority were only entitled to toga praetexta, but when they reached the age of 15, they assumed toga virilis. For priests, toga trabea was reserved, and only the emperor could wear a purple toga (toga purpurea). Toga praetexta was also available to officials (consuls, praetors, censors, dictators). A characteristic feature of the praetexta gown was the purple trail 5-8 cm wide, initially located along the bottom rounded edge, then along the edge of the sine.

Adequate to the circumstances, the Romans were also entitled to other gowns. During the triumph, the Roman chief put on a purple toga (toga purpurea), often coloured (toga picta), which eventually became the costume of the emperor (trabea). For the time of mourning or political crisis, a dark toga – toga pulla – was worn.

Putting on a toga was a difficult act, not to say burdensome. The strip of material was folded lengthwise, one end imposed on the left shoulder, the toga was applied to the back, and the other end was carried out under the right shoulder and from the front again thrown onto the left shoulder. To facilitate this extremely careful activity, wealthy citizens had a special slave for this purpose, called the vestiplicus.

On frosty days or in winter, the Romans wrapped themselves in a wide covering (lena), while workers were served by a wide coat (sagum), fastened with a clasp (fibulae). After the conquest of Gaul by the Roman Empire, sagum was one of Gaul’s main export goods. The coat was widespread throughout the empire so the craftsman involved in the production of fabrics was called Latin sagarius.

After gymnastic exercises, a warm, wide blanket (endromis) was wrapped around a body. In hot weather, wide-brimmed hats (causia or petasus) were used. Women were protected from the sun under the dome of an umbrella (umbrella or umbraculum).

In early Rome, women also wore a robe, tightly covering not only their breasts but also their faces. It was almost identical to the men’s. Over time, there were some differences in the clothing of both sexes. Only prostitutes wore the gown (toga muliebris), while other citizens wore tunications. A married woman was putting on a table, a long, wide dress with a belt. During Augustus’ reign, a more elegant dress appeared (cyclas). Roman women also wore alicula, a short cape covering their shoulders.

From the early republic, women wore a cape covering their shoulders (ricinium), which was replaced by palla during the empire, a long strip of material imposed on the dress. The robe was available to all women and distinguished the legal status of the woman by the way she was founded. Citizens threw one end of the fabric over their left shoulder, covered it with their backs and, leading forward under the right shoulder, threw the other end over their left shoulder again. Other women rejected some of the fabric from above so that a “kick” was formed at the front and back, which they fastened with safety pins. Ricinium was used only for religious ceremonies.

The decline of the republic introduced a slight revolution in clothing. Increasingly, instead of a gown, a coat (lacerna) or a light robe (synthesis) was worn. Lacerna was at first a soldier coat, from the time of the empire it became a civilian coat. Her appearance depended on the citizen’s property status. In the rich, she shimmered with colours, while the villagers could only choose grey. Synthesis, in turn, was an elegant outfit worn only at parties or during Saturnalia, usually in red or green. Paenula, a coat with a hood put on over the head, served as protection during travel. Paenula was made either from leather (paenula scortae) or from very heavy felt (paenula gausapina). Women also used this robe. For protection against rain, a coat decorated with a large hood (bardocullus, birrus was also used. pallium was also used – a typical coat modelled on the Greek himationie. fabric, which in Rome was more ornate and more expensive. As cucullus and cucullati mean “hood”, the Romans also used this term for a hooded coat. In the Middle Ages, which was also used in Rome, a hood with a collar was worn by farmers and hunters – aglicula. Caracalla (the name of the later Emperor Caracalla), in turn, it was a tunic with a cloak; it is possible that it was worn mainly by children.

In addition, the emperors wore a paludamentum. It was a Roman wool coat reaching to the knees or below the calves, fastened on the right shoulder. The emperors wore it purple and the chiefs were crimson, while the officers were white. Soldiers wore paludamentum of thick wool of natural color (especially during the empire).

Trousers

In Rome, subligaculum – loincloth was worn in the form of pants. It was a belt of linen fabric tied at the waist, and its purpose was to protect the hips. Generally, they wore them under other clothes, but for example, athletes wore them on their own.

Another type of pants was femoralia – quite narrow and short shorts worn first by the army and then worn by the emperor and ordinary people. They were sewn and made of linen.

Colour of clothing

The range of colours used to produce Roman clothing was achieved through a complicated dyeing process. Expensive fabrics were imported from abroad, and their colouring was equivalent to expensive. The red dye used to achieve deep purple and light crimson came from insects from the Mediterranean. Lighter and darker colours were much more expensive and were intended for the higher social classes. All colours were achieved by organic (plant or animal – mainly insects).

The issue of luxury in the Roman strata was so large that the authorities decided on the need to regulate the consumption sphere. To this end, the so-called Sumptuariae Leges (“Law against lavishness”), clearly limited the expenses of the Romans. These provisions were also applied to clothing – the issue of who could wear clothes and what shade was regulated. For Caesars, the purple colour was reserved (dye is extremely difficult to achieve, and therefore very expensive). It was the so-called Tyrian purple. It is obtained from secretions of the sea snail family of thistles, mainly Haustellum brandaris. The emperor also had his dress decorated with golden thread, which was to emphasize the uniqueness of the ruler. The Act also regulated the issue of the number of belts in tunics and, for example, forbade men to wear silk clothing in the early days of the principate.

The number of pigments in Rome increased with the conquest and learning of new cultures in the east. The Romans, who were great traders, were able to maintain close business relationships, e.g., with China, which exported silk. In this way, the Romans obtained many dyes and learned the technology of their manufacture.

Various types of additives were used to achieve a given colour. Such were: wine, salt, shells, mosses, sheep urine, lentils, mushrooms, vinegar, wild cucumbers, nuts, insects, barley malt, plants, bark, roots, berries and flowers. The simplest colours were achieved in the simplest possible ways, looking for the best raw materials in the Roman provinces.

The Romans were able to achieve the following colours: white, purple, blue, red, crimson, orange, yellow, green, brown, and black.

As mentioned before, the noblest and most expensive colour was purple. Its name – Tyrian purple – is taken from its place of origin, in present-day Lebanon, from Tire. The original creators of this colour were the Phoenicians, who in order to obtain purple had to crush thousands of sea shells first. Apparently, in order to colour one Roman gown needed close to 10,000 shells.

To achieve yellow, saffron was dried and then cooked with other flowers. Another cheaper dye was the yellowish reseda plant.

Indigo was one of the more expensive colours. In contrast to the blue colour, which was easily achieved, it was intended more for the upper classes. The colour was obtained as a result of the fermentation of the indigo plant, which was imported from India.

Blue was easy to obtain and widely available. It was obtained from a plant – a barrow plant. Among other things, Celtic warriors stained their faces and bodies with blue with an extract of décor. An interesting fact is that in 60 CE Boadicea – the queen of Iceans living in eastern England, led her army to fight the Romans completely undressed, painted only with the blue dye obtained from the barbarian unit.

Scarlet was obtained from dried and then fermented female Kermes insects that could be found in southern Europe on oaks

Greenery in various shades was obtained from lichen or lichen. Colours of the type: red, orange, brown, and pink were achieved largely from senba, which, together with other ingredients, took the right colour.

Headgear

There was galerus, that is, an ordinary tight cap; petasos, women’s and men’s wide-brimmed hat of Greek origin; pileus, a men’s felt conical cap worn rather by the poor; and alicula, the hood as a headgear worn without a cloak. The name pileus was generally used to describe headgear. A specific type of headgear could be pileus pannonicus cylindrical in shape and made of wool or fur, or pileus phrygitius – slightly pointed, sometimes with a nose to the front, made of wool and felt.

Footwear

Certainly, Roman shoemakers (sutor) were very good craftsmen, and their products were widely worn throughout the Mediterranean area.

The difference between the male and female footwear was small. Romans and Romans usually wore sandals (sandalia or soleae) tied with a strap around the ankle.

Shoes (calcei – from the word calx or “heel”), in turn, were standard output footwear and together with the toga was the national costume of the upper classes. There were two types of calcei.

- Calceus patricius, made of red leather, with a high sole, closed at the back with a leather belt, in the front had cuts, through which straps were used for lacing. Kings, consuls and winners used this type of footwear.

- Calceus senatorius, made of black leather and finished with an ivory buckle (lunula) in the shape of a crescent.

Unlike the original calcei, the sandals were home footwear. It was considered a great act to see a Roman walking to the banquet in sandals. Therefore, wealthy citizens went to parties with slaves who wore sandals so that they could easily change their footwear.

Leather slippers (crepidae) were still in use, held with straps tied through the holes. Another type of slipper was soccus – a low, lightweight boot, used only by effeminate men and women. Serious people usually used high platform shoes (cothurnus). Soccus was also the footwear used in comedy when the wedge belonged to the costume of the tragic author.

Military footwear was caligae. They were shoes completely closed, laced. Actors wore slippers (socci). Slaves and the public wore clogs with thick soles (sculponea), or wrapped their legs with only a scrap of thick skin (pero). It is worth adding that researchers found in North Yorkshire that Romans could wear socks with sandals.

Ornaments and jewellery

In ancient Rome, fashion developed more than in Greece, and jewellery became a fantastic complement to the image of a fashionable Roman woman. The main reason for this was the difference in perception of the role of women.

Men also wore rings, originally of iron with time also gold, which confirmed the authenticity of the issued documents. Originally they were made of iron, but over time they were covered with gold.

The boys wore amulets (bull) on their necks to protect them against the unforeseen effects of natural forces. They wore them up to 16 years old. Girls also wore such charms – but these were until the moment they got married. Women most often wore brooches (fibula), tiaras, earrings, and necklaces. They also used fans.

Beards and hairstyles

The tradition of intricately prepared beards was quite common among Greeks and Etruscans (the Romans borrowed many elements of their culture). However, with the advent of Alexander of Macedon, the custom of shaving facial hair also appeared. This fashion spread quickly across Great Greece, which also included the south of the Apennine Peninsula. From there, the “idea” of shaving a beard moved to Rome.

It is believed that the first of the great Romans who began to promote a perfectly shaved face was Scipio Africanus who shaved every day. In addition, in the third century BCE, many hairdressers moved from Greek Sicily to Rome and opened shops and “hair salons”.

A qualified hairdresser (tonsor) in Rome could make a career and earn good money. It should be noted, however, that shaving was not very pleasant and easy at the time. The Romans used much worse steel than we do today, and it has often happened that the razor (novacula) quickly blunted. In addition to shaving, cutting and waxing, hairdressers also offered the removal of individual facial hair with tweezers.

Rome, however, was susceptible to all fashion in other lands. In the late republic, a small and well-groomed beard (barbula) was popular with young men. Still, a shaved face was preferred. This custom survived until the time of Emperor Hadrian, who again adopted the idea of wearing a beard. There are two approaches to the reason for this change. Either the emperor was again under Greek influence, or he had a mutilated face – he tried to hide his scars at all costs. Whatever the reason, Hadrian set a new fashion for men who preferred facial hair from then on.

Another breakthrough was the reign of Constantine the Great, which restored the habit of shaving and began another trend in Roman society that lasted until the fall of Rome in 476 AD

Hairstyle changed very often in Rome. Sometimes women wore a wig, with the blonde wig indicating that the woman is a prostitute.

Initially, the hairstyle was very simple. During the reign of the Flavian dynasty, fancy hairstyles began to appear, including the so-called bird’s nest. The most complicated hair arrangement was intended for special moments, such as weddings. Wealthy women used the slaves (ornatrices or ciniflones) to style their hair.

Roman women, with high-combed hair, tied a long ribbon (vitta). Mothers tied their hair with a double white bandage, while the usual one was intended only for virgins.

Women’s hairstyles changed depending on the fashion in a given period. In the earliest era, they were combed easily. The hair was separated by a parting in the middle of the head, collected from behind in a bun or ponytail, sometimes leaving small bangs in front of the curls. From the August period, the hairstyles became more and more sophisticated, reaching their highest level for the Flavians, when women’s hairstyles became almost gigantic curl designs (the so-called wasp nest).

They were combed mainly with bronze, bone or ivory combs, and special modelling tongs (calamistrum) formed to make curls and heated on the stove. Today, women used hairpins, ribbons, nets and various hairpins, which increased the volume of hairstyles. Hair was also dyed and bleached. Frequently used spuma batava gave a blonde shade of copper. Roman women valued the blond hair of Gaul women, from which wigs were made for them. In addition, they removed grey hair from the toilet, which was not elegant enough for them.