The oldest Praceltic name for a war chariot recorded among the Gauls by older ancient Greek authors is reda – a word with a very ancient Proto-Indo-European lineage- a similar one exists in the language of which the Protaindoarian Vedas were written. In the indigenous Iranian language the word riad, meaning driving, has been preserved.

The fight of ancient heroes on chariots has been preserved in the old legendary Irish novels, such as Táin Bó Cúailnge, which tells the story of the warrior Cú Chulainn during the time of Queen Medb (presumably during the reign of Roman Augustus).

The Romans had their own “peace” vehicles of this type – they were used for rides, parades (triumphs) and races. Two-sided chariots were called biga.

The Romans got to know, and quite early in their history, the expansive Gauls who had arrived and settled in Italian territory, and fought them. So early that old Celtic word entered their language as rheda/raeda, where it began to denote a carriage with a different function. Another Gallic word came to the Romans from the Gauls, appearing in Latin as essedum, also meaning “combat car”- it served, inter alia, to fight at gladiatorial games, the Romans called warriors/gladiators fighting on such carts essedarii. The word essedum is related to the Latin sedeo and the Polish “sit”, which rather emphasizes its transport functions over longer distances – when, on the other hand, the chariot’s charge required a standing position.

The Celts became famous in antiquity, in the eyes of the Greeks and Romans, as masters of all kinds of vehicles, carts and carriages, in a word – wheeled transport, and on a large scale, both in relation to dead goods and to people. Their great migrations, which they went with women and children, over great distances (some tribes went to Asia Minor) were remembered. The last such migration happened during Caesar – it was the Helvetian migration he foiled, which started his military activity in Gaul.

So were there, like the much later Hussite Czechs in the times of our Grunwald- masters of the military use of rolling stock, which, by the way, reached back to the very old pro-Indo-European tradition of migration.

Contrary to popular belief- and different from, for example, the ancient Persians- Celtic warriors, at least in Roman times, did not clash with the enemy directly, even standing (let alone sitting) on a chariot. The chariot was used to transport it to the battlefield, it was thrown with javelins and bows were fired- and simulated charges, thus creating confusion in the ranks of the opponent, causing panic- So it was a means of a very mobile and also “psychological” fight.

But after bringing a warrior to the battlefield, the warrior jumped off the chariot and fought on foot… as long as it suited him. The chariots stood nearby, ready for a swift manoeuvre, often to retreat “to the desired position.”

Let us give the floor to the Greek historian of the Empire, Diodorus Siculus (80 – c. 20 BCE):

(…) they go into battle the Gauls use chariots drawn by two horses, which carry the charioteer and the warrior; and when they encounter cavalry in the fighting they first hurl their javelins at the enemy and then step down from their chariots and join battle with their swords.

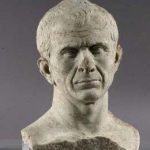

– Julius Caesar, Gallic War IV

We also have an account of Caesar himself on this subject, on whom Celtic chariots apparently made a great impression. Let us give the floor to him himself:

(…) In chariot fighting the Britons begin by driving all over the field hurling javelins, and generally the terror inspired by the horses and the noise of the wheels are sufficient to throw their opponents’ ranks into disorder. Then, after making their way between the squadrons of their own cavalry, they jump down from the chariot and engage on foot. In the meantime their charioteers retire a short distance from the battle and place the chariots in such a position that their masters, if hard pressed by numbers, have an easy means of retreat to their own lines. Thus they combine the mobility of cavalry with the staying power of infantry; and by daily training and practice they attain such proficiency that even on a steep incline they are able to control the horses at full gallop, and to check and turn them in a moment. They can run along the chariot pole, stand on the yoke, and get back into the chariot as quick as lightning (…)

– Julius Caesar, Gallic War IV

Of course, the confrontation of the methodical, accustomed to the iron discipline and team action of the Romans with this technique and method of combat was, above all, extremely burdensome. The Britons fought spontaneously and individually, each chariot had a lot of freedom to move and choose the actions appropriate to the moment. Their scope included, in addition to hand-to-hand combat with swords or clubs- also both archery and javelin throwing. The chariot warrior was thus an “orchestra man” in the eyes of the Romans, who had been taught to keep their place in the formation and to stick to their strictly defined, specialized role. The chariot and its crew- it was a very independent battle unit.

This also applied to the possibilities of battle deception- apparent, confusing, simulation activities- All these mock charges and retreats… It meant tremendous unpredictability. The Romans must have felt the same (around the same period) when confronted with the incredibly mobile horse archers of the Scythians and Iranian Parthians. And even more- like over a thousand years later, Polish knights in the fight near Legnica, with the Mongolian horse archers of Batu Khan.

This spontaneity and individualism of the Celtic warriors’ fight, this theatrical show off of their skirmishers, however, also hid many weaknesses- in the long run, these “martial artists” did not control the entire battle scene, they were guilty of a lack of coordination… they had to lose to the methodical, tightly coordinated actions of the Romans, planned as in a chess game many moves ahead- whose commanders were taught never to lose sight of the entire battle, to be able to anticipate and direct huge teams of people.

Contrary to what may appear from the above descriptions, British Celts in Caesar’s time were no strangers to riding, they used horse riding and also had riding units.

It must be remembered that the tribes of southern Britain with whom Caesar dealt after landing, like the Trinovants and the Katuwellauns, are not some indigenous people, people of Britain for many centuries, i.e. “old Britons”, Pretanoi in the early Greek authors. Celts mixed with the older, pre-Indo-European layer of the population (its relic was probably the tribes of the Silurians and Scottish Caledons). They were famous for their wartime face and body paints. On the contrary, those from the coastal south of the Island were relatively recent immigrants from mainland Gaul. The beginnings of this last Celtic settlement wave date back to the 3rd century BCE at the earliest. Migrations lasted almost to the time of Caesar, that is, to the last decades of the old era.

According to Caesar’s inquiries, the Gauls of his contemporaries remembered how some immigrant groups settled in Britain had come to the Island during their lifetime, and their communities established in Britain bore the same names as they used to in Gaul. The immigrants included, among others the tribes of the Trinity, Katuwellaun, Paris and Iceni (Iken as it was then pronounced).

Undoubtedly, these newcomers mingled with the “old Britons”, absorbed them and often subjugated them. Thus, they took over their traditions and customs, it is difficult to say to what extent. This also applies to chariots. These visitors from Gaul already knew cavalry as a military formation, did they remember the chariots from Gaul that their ancestors had used- and that memory was refreshed when they encountered chariot fighting “old” Britons- therefore they adopted this way of fighting; it should be noted that it was extremely prestigious, and perfectly suited the assimilation of newcomers, inter-tribal relations (and conflicts) in Britain. It does not mean, however, that they completely resigned from the well-known riding and use of cavalry as a military formation- an example is the Atrebats of Comius.

However, they probably recognized the superiority of the Roman cavalry and consciously chose the archaic way of fighting on chariots to surprise and confuse the Romans. Considering the Roman legion was seen as a very compact, independent and self-sufficient strike force- the main goal of the Celtic defenders was probably to break this cohesion and distract the enemy- rightly convinced that small groups are easier to deal with. The chariots’ unpredictable manoeuvres were perfect for this.

There was probably also a psychological effect. The Britons, especially those recent immigrants from Gaul, knew the Romans. The chariot was surrounded by a sacred aura for the Romans, the triumph of a Roman leader was, after all, a religious ceremony. The chariot was for them the vehicle of the gods, above all the “father” of Rome, the god of war of Mars. And they were also, as we would say today, superstitious. The use of chariots by the Britons sowed in the minds of Roman soldiers a strong suggestion that their enemies had supernatural powers on their side that could not be defeated…

Unfortunately, there was some bluff to this game and it failed miserably in the long run. Maybe it only allowed, thanks to the possibility of a quick retreat, to avoid too many bloody casualties among the select military cadre- After all, the military aristocracy was the backbone of these tribal political organisms, it should not be exposed to easy extermination in unequal battles. The Romans, in turn, interpreted it as “lack of perseverance” in combat, which greatly increased their morale.

“Little” guerrilla warfare, guerrilla, guerrillas… obstructing supplies, tearing the enemy and quickly disappearing turned out to be much more effective… But that’s a topic for another story.