Chapters

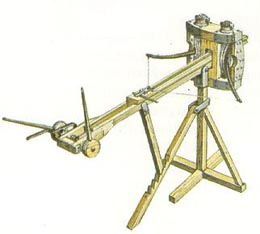

Scorpio was a small machine used to throw projectiles, resembling the bolts of medieval crossbows. Scorpio was an extremely precise and effective machine, and therefore enemies were often terrified of its presence on the battlefield. With the evolution of the Roman war machines, the cheiroballistra appeared.

She looked like a ballista, but was much smaller than her. Scorpion missiles flew on a flat track for a distance of up to 600 meters. Small ones with a range of up to 200 meters were used en masse, which were perfect for destroying enemy formations.

Scorpions were used by the Romans in the 1950s BCE. The first records of these machines, however, are from Polybios (8.5.6) and refer to the Syracuse arsenal during the Second Punic War.

During the Roman Republic and early empire, it was standard for one legion to have 60 scorpio or one for each century. Scorpions essentially had two functions: their precision was able to hit any enemy up to 100 meters away. During the siege of Avaricum in the Gallic War, Julius Caesar describes the lethal effectiveness of these scorpio machines. In turn, using a parabolic trajectory, the machine was able to fire up to 400 meters (with 3-4 shots per minute) – but the effectiveness was lower then.

Scorpions were usually placed on a hill or other high hill, protected by a legion. Thanks to this setting, 60 scorpio was able to fire up to 240 bolts per minute. The mass and speed of the missiles allowed them to penetrate the shield and even neutralize the enemy.

Research

The work of Vitruvius “De Architectura” triggers strong dilemmas and heated discussions as well as emotions. An example would be Book X, and most of all its tenth chapter deals with heavy throwing weapons (scorpio and ballista). At the beginning of the 20th century, on the basis of new archaeological discoveries and the constantly expanding list of finds in the field of the Roman military, the problem of Vitruvius’ credibility became a field of reviving disputes and discussions. It is worth mentioning here, for example, the finds of fragments of scorpio from Ampurias (Spain), and Saalburg (Germany), on the basis of which E. Schramm reconstructed several copies of this combat machine, truly “pioneering” and groundbreaking for those times, giving rise and hints for further this type of activities that are currently included in the so-called experimental archaeology, otherwise known as experimental archaeology.

Subsequent, more in-depth and detailed studies of the previous finds of fragments of Roman scorpions, ballistas and their missiles, especially from Europe, as well as new archaeological discoveries (such as in Xanten – Wardt, Carlisle), led to a kind of confusion and revival of the dispute around the characters Vitruvius. The museum collections expanded to include numerous exhibits inextricably linked with Roman “ballistics”, although they were not always parts of throwing machines. The vast majority were stone balls (projectiles for the larger variant, referred to by Vitruvius as ballista) and rays (the main wooden part of the arrows), and sometimes even fully complete projectiles, which were almost automatically classified and assigned to a specific a copy of scorpio – usually found in the same town or position. This is because the principle of a specific “unitarism” – their identity, was often adopted. The rays of arrows from Dura-Europos attracted particular attention from researchers, probably due to their numbers. Their length usually varies between 300 and 375 mm, so they are much shorter than arrows to bows, although they exceed them in terms of mass (up to 28 mm in diameter) and weight.

And at this point a significant dilemma and doubts arise regarding the credibility of Vitruvius’ description of throwing machines, especially their proportions (both scorpio and ballista). In the introduction to his considerations (Book X), the author would seem to state clearly and clearly that the diameter of the holes in the frame (and also the diameter of the so-called strings – twisted together at least a dozen ropes that give the projectile lifting force) should be 1/9 of the projectile’s length: “Omnes proportiones eorum organorum ratiocinatorum ex proposita sagittae longitudine, quam id organum mittere debet, eiusque nonae partis fit foraminis in capitulis magnitudo, per quae tenduntur nervi torti, qui bracchia continere ipsum lat tamen debent. Eorque foraminum altitudum capitul”. Vitruvius made the dimensions of the entire machine dependent on the design assumptions adopted in this way, justifying them with the need to adapt them to the sizes and weights of the fired projectiles.

Theoretically correct and logical assumption, but contrary to the meaning of the previously discussed archaeological material, in which one can notice a significant discrepancy between the proportions – between the length of the scorpion arrow spars found and the diameters of the preserved so-called bearings. They were bronze bushings through which (as well as through the holes in the scorpio frame) the strings (ropes twisted many times) passed vertically. According to the aforementioned Vitruvian principle, these proportions should be 9: 1, so with the length of arrows varying between 270 and 375 mm, the mentioned internal diameter of the bearings and the diameter of the twisted strings should not be greater than 30-41.6 mm. Meanwhile, the archaeological material shows something completely different. In the found copies of the so-called bearings classified as derived from scorpio, the dimensions are almost 50% larger.