If a Roman citizen wanted to commit suicide, he had to first submit a request to the senate with a justification and a request for positive consideration. If the request was approved, the citizen received poison (hemlock) free of charge1. Then he drank it or put it on a sword with which he then pierced himself. Slaves, soldiers2and people sentenced to death could not decide to commit suicide. The reason was simple: losing them was an economic cost.

Suicide in the world of ancient Rome was extremely common. Many people, sometimes prominent like Seneca the Younger, had to choose to commit suicide, with the choice of keeping honour or dying at the hands of praetorian. For the Romans, killing oneself was a sign of great courage and a chance to maintain honour. This solution was better than living in the face of disgrace or defeat. According to the Stoics, death was a guarantee of liberation and the only way to avoid dishonour.

This perception of suicide was due to the influence of Greek culture, which considered taking your life to be trespassing as an attempt to understand death and get rid of the fear of the unknown. A common method of taking one’s own life in Rome was to “open one’s veins”, that is, to cut them and bleed them out. Another way was to stab himself in the stomach with a dagger, incl. the famous Lucrezia did so.

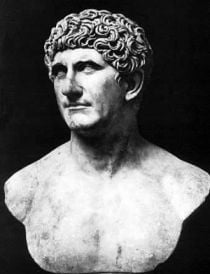

The Romans accepted taking their own lives out of a desire to maintain honour. However, they did not respect the situation when, in their opinion, the reason for taking their lives was dictated by private matters. For example, Roman society felt very negatively about the suicide of Marcus Antony, who had committed suicide out of love.

When it comes to views on the fact of suicide, the Romans essentially relied on the arguments of the Greeks. Suicide was accepted only in certain cases: senile infirmity (this was what Zeno of Kition used in his decision), loss of honour, ananke (coercion), irreversible misfortune.

In Plato’s case, what is supposed to stop us from committing suicide is the necessity to meet the tasks set for us by the gods, invoking the doctrine of Filolaos. Both Plato and Aristotle pointed to the anti-state nature of such an act.

At one time in Rome there was something like a cult of suicide death; what is most clearly expressed in the writings of Seneca, who in his work “On providence”, writing about the death of Cato, considers it one of the few spectacles on earth truly worthy of Jupiter’s attention.

And in Letter 70 (“Moral letters to Lucilius”) we find the following passage:

You need not think that none but great men have had the strength to burst the bonds of human servitude.

In Rome, suicide in the face of a shameful death was an expression of willpower. In a certain period, there was a kind of theatricalisation of suicides. A person who wanted to take his own life would have a feast and invite friends to whom he was saying goodbye. At the same time, interestingly, despite widespread admiration, suicide under Roman law was sometimes treated as taking the life of a relative. This was especially true at times when suicides increased. The state tried to intervene, and then frequent repression was the seizure of property and desecration of the body. We do not even have general numbers on how many people died by their own hand, but based on the works of Seneca, Tacitus, Suetonius or Pliny the Elder and Younger, we may assume that it was a fairly common practice.

The law did not criminalize the suicides of free people; this only applied to slaves and, more importantly, to people who were already condemned to death. Many, anticipating execution and having a death sentence issued by the state – which was associated with the possible confiscation of property – fled from it, for the good of the family, taking their own lives. Tacitus describes such an advance of judgment as pretium festinadi. On the other hand, this law was not always in force, because Makron, the prefect of praetorians, after hearing the death sentence, decided to take his life, and his fortune did not remain with the family. Ulpian mentions in his Digest (XXVIII, 3, 6-7) that this record disappeared after Cicero’s death.

In fact, there was no established, even customary, pattern of ceremonial. Below is a representation of the death of Gaius Petronius:

He declined to tolerate further the delays of fear or hope; yet still did not hurry to take his life, but caused his already severed arteries to be bound up to meet his whim, then opened them once more, and began to converse with his friends, in no grave strain and with no view to the fame of a stout-hearted ending. He listened to them as they rehearsed, not discourses upon the immortality of the soul39 or the doctrines of philosophy, but light songs and frivolous verses. Some of his slaves tasted of his bounty, a few of the lash. He took his place at dinner, and drowsed a little, so that death, if compulsory, should at least resemble nature. Not even in his will did he follow the routine of suicide by flattering Nero or Tigellinus or another of the mighty, but — prefixing the names of the various catamites and women — detailed the imperial debauches and the novel features of each act of lust, and sent the document under seal to Nero. His signet-ring he broke, lest it should render dangerous service later.

While Nero doubted how the character of his nights was gaining publicity, there suggested itself the name of Silia — the wife of a senator, and therefore a woman of some note, requisitioned by himself for every form of lubricity, and on terms of the closest intimacy with Petronius. She was now driven into exile for failing to observe silence upon what she had seen and undergone. Here the motive was a hatred of his own. But Minucius Thermus, an ex-praetor, he sacrificed to the animosities of Tigellinus. For a freedman of Thermus had brought certain damaging charges against the favourite, which he himself expiated by the pains of torture, his patron by an unmerited death.

– Tacitus, Annales, XVI.19-20

Less “theatrical” methods were also common. Dolabella, Marcus Antony with his slave Eros, Scipio Metellus, Cato the Younger of Uticena died from an ordinary sword. Emperor Nero pierced his throat with a dagger, a knife was also used by Caecinus Paetus with his wife Aria. Worthy of description is the death of Emperor Marcus Otho, who reportedly chose to die to avoid further bloodshed between the Romans in 69 CE. This is how Suetonius describes it:

When he had thus made his preparations and was now resolved upon death, learning from a disturbance which meantime arose that those who were beginning to depart and leave the camp were being seized and detained as deserters, he said “Let us add this one more night to our life” (these were his very words), and he forbade the offering of violence to anyone. Leaving the door of his bedroom open until a late hour, he gave the privilege of speaking with him to all who wished to come in. After that, quenching his thirst with a draught of cold water, he caught up two daggers, and having tried the point of both of them, put one under his pillow. Then closing the doors, he slept very soundly. When he at last woke up at about daylight, he stabbed himself with a single stroke under the left breast; and now concealing the wound, and now showing it to those who rushed in at his first groan, he breathed his last and was hastily buried (for such were his orders) in the thirty-eighth year of his age and on the ninety-fifth day of his reign.

Neither Otho’s person nor his bearing suggested such great courage. He is said to have been of moderate height, splay-footed and bandy-legged, but almost feminine in his care of his person. He p247 had the hair of his body plucked out, and because of the thinness of his locks wore a wig so carefully fashioned and fitted to his head, that no one suspected it. Moreover, they say that he used to shave every day and smear his face with moist bread, beginning the practice with the appearance of the first down, so as never to have a beard; also that he used to celebrate the rites of Isis publicly in the linen garment prescribed by the cult. I am inclined to think that it was because of these habits that a death so little in harmony with his life excited the greater marvel. Many of the soldiers who were present kissed his hands and feet as he lay dead, weeping bitterly and calling him the bravest of men and an incomparable emperor, and then at once slew themselves beside his bier. Many of those who were absent too, on receiving the news attacked and killed one another from sheer grief. In short the greater part of those who had hated him most bitterly while he lived lauded him to the skies when he was dead; and it was even commonly declared that he had put an end to Galba, not so much for the sake of ruling, as of restoring the republic and liberty.

– Suetonius, Otho, 11-12

Seneca the Younger served himself a death similar to Petronius: he opened his veins, swallowed hemlock, and finally most likely died from the steam. The most famous suicide at the time – Lucrezia, the disgraced wife of Tarquinius Callatinus, was also a dagger; the strangest path was reportedly chosen by the wife of Brutus – Porcia, who swallowed hot coals3.

In a letter, Seneca mentions a Germanic captive who committed suicide by thrusting a faecal brush down his throat4.