Chapters

Probably the first inhabitants of Rome were breeders, farming came later. The Roman state was an agricultural society at the beginning of the 3rd century BCE. Most of the empire’s subjects worked in the fields. They were small, several-hectare farms. After the Second Punic War, the situation of farmers changed, not to say deteriorated.

They suffered poverty, many peasants spent many years in the army, and the land was wasted, while others sold their land to great owners and supplied plebs in the town. When Rome expanded to include provinces that supplied grain, their production ceased to be profitable in Italy. Some farmers switched to breeding (cows, sheep, goats, pigs and horses). In the first century BCE, small-scale peasants were still getting rid of their land, and in Italy, huge latifundia began to multiply, on which colonies or slaves worked. The first latifundia were established in Italy in the 3rd century BCE, as a result of combining leases of public land, buying or seizing land for small farmers for debt, and purchasing land of proscribed people for a song. In 133-123 BCE Tiberius Gracchus and Gaius Gracchus (plebeian tribunes) tried to introduce an agrarian reform that was to parcel out latifundia. However, the reform was unsuccessful. The rapid influx of slaves from the Roman conquests finally eliminated free citizens from farm work. Pliny the Elder used the phrase: “great estates have lost Italy” (Latifundia perdidere Italiam). Thus, the Roman historian and writer emphasized the situation of the Roman peasant who could not withstand competition with the great latifundia.

Cultivation and working conditions varied. It was puzzling to constantly idealize rural life. Many Romans found the life of farmers easy and pleasant, not realizing the real hardships of rural life (bad weather, primitive tools). There were also poems praising the work of the shepherds.

Senators invested in lands in Italy, but also, encouraged by the peace ruling in Empire, used the fertile soil abroad. The Romans cultivated more land by moving Mediterranean vegetation and proven farming methods north to Gaul, the Rhine Valley, and the Balkan Peninsula.

Grain, wool, olives, and wine were the main trading commodities throughout the Empire. There were Roman vineyards in Gaul, and olive groves were grown in North Africa. The Romans also learned new cultivation techniques in humid climates, which allowed them to use land in northern Gaul and Britain. Landowners lived in cities – the richest of them lived in Rome itself. The largest landed estates were powerful enterprises. In one such estate near the city of Pompeii (known as Boscatrecase) she stored 100,000 jars of wine. Large estates in other provinces had much lower labour costs, which was to the detriment of agriculture in Italy. As a result, Rome imported wheat from Egypt and Africa, wine from Gaul, oil from Spain and Africa, figs, dates and plums from Syria, cereals from the south, and vegetables from the northern provinces.

An interesting fact is that in the vicinity of Smyrna (now Izmir, Turkey), the Romans grew rice.

During the early empire, there was a change in the agriculture of Italy, largely due to the problem of the labour force. The ethnic composition of slaves and their preparation for work on a farm changed. Instead of highly skilled slaves from Hellenistic countries, whose enormous influx was characterized by the decline of the republic, at the beginning of the empire, mostly “northern barbarians” came to Rome: Gauls, Germans, and Britain. They did not know how to work in vineyards and olive plantations; they knew only pastoralism and, at best, the cultivation of cereals, so they could only be employed in the vineyards as unskilled workers. At this time, in many estates manual work on the land (hoeing) is abandoned, and a harrow is introduced, which results in savings in terms of manpower.

However, the most important factor in losing Italy’s economic advantage was the competition of the western provinces. Countries such as: Gaul, Spain or Dalmatia had very good natural conditions for fruit growing. Gradually, the people of these provinces learned the higher agrarian technique and began to massively plant vineyards and olive orchards. Gaul grew into the main wine producer in the western part of the Empire, and olive oil from Spain began to crowd Italian oil from the markets.

An important Roman work concerning agriculture is Marcus Porcius Cato – “About the farm” (De argi cultura) from the 2nd century BCE. Cato popularized the villa concept in Roman literature – a medium-sized property focused on selling its products. Cato owned many properties in Campania and shared his experience in managing them with the Romans in general. He believed that an ideal land estate should have between 100 and 240 yugers of land (25-60 ha). The smaller one might have been villa geared towards viticulture (100 Jugers – 25 ha), but it required a relatively large amount of work. Therefore, it was necessary to purchase no less than 16 slaves for it.

The estate focused on the production of olives – olive orchards – could have up to 240 Jugers (60 ha). A group of 13 slaves was enough for it. Cato devoted a lot of space to the organization of slave labor. At the head of the slaves he put an estate manager, known as vilicus, who, being a slave, had several privileges, including the right to have a wife, called vilica, who ran the farm. Ordinary slaves lived in ergastula, which had a prison character. They often worked chained to prevent their escape. Kato recommended feeding them solidly during the field works and saving on food in winter. He also believed that a slave could not be allowed to idle. He must be occupied from dawn to dusk so that after work he can only think about sleeping. The old and the sick had to be disposed of as quickly as possible by selling them.

The type of farm promoted by Cato spread especially around Rome, numerous Villae were built in Lazio and Campania, and in the areas surrounding the larger cities of the Empire. These were groups of often dispersed estates owned by individual nobilitas. Some of them are of the Catholic villa type, others as farms cultivated by tenants. The description of the already established way of running a farm appears in the works of Cicero at the turn of the 2nd and 1st centuries BCE.

Agricultural calendar according to Marcus Terentius Varro |

Varro (116 – 27 BCE) wrote De re rustica, a textbook on agriculture, valued until modern times. It consists of three books in the form of dialogues, each of which is devoted to a different topic. When writing this treatise, the author used his own experience, literature on the subject and the knowledge of people experienced in this field.

In each of these periods, Varron recommends carrying out specific agricultural work and so in:

|

Ager publicus

In ancient Rome, there were the so-called public lands (Ager publicus), which were public land administered by the state. According to tradition, the founder of ager publicus was Romulus, who allocated plots of land to the citizens of Rome for 2 jugers (a unit of area corresponding to the later morga), while the rest of the land was allocated to collective cultivation. The ager publicus consisted of lands taken from the enemy, from rebellious allies, and “no man’s lands”. A large part of them were taken from, for example, Italian cities that supported Hannibal.

Each citizen could use 500 jugers (about 125 hectares) of public land – such a limit was to be introduced by the leges Liciniae Sextiae from 367 BCE, but part of the state land was auctioned, the part unlawfully appropriated by wealthy citizens as “nobody’s” (ager occupationis). In the second half of the second century BCE, many wealthy landowners occupied many times more, while vast numbers of poor citizens were deprived of land at all. The Gracchi reform (begun in 133 BCE) was to end this situation.

In the 1st century BCE, Roman leaders: Sulla, Julius Caesar did Pompey the Great pursued a policy of giving away public land to veterans. It is worth mentioning Julius Caesar introduced two agrarian laws in Campania in 59 BCE The main change was the prohibition of compulsory purchase of land without the consent of the owner. The earth was also allowed to fill, in the first place promised to Pompey’s deserving veterans. These most important points of the reform had to be approved by the Senate.

In imperial times, ager publicus was enormous and formally belonged to the emperor. However, it was mostly privately owned.

Mills

Initially, a mortar with a pestle was used to grind the grain, and in later times, querns consisted of two flat stones, where the upper stone was moved along the lower one. Throughout the day, on such querns, it was possible to grind grain into flour for 8 people (approx. 3 kg). Most often this “honourable” work was performed by a slave. As the burrs progressed, they were given a circular shape so that the upper stone rotated around its axis along the lower stone (the oldest burrs of this type come from around 1000 BCE), thanks to which the slave operating the burrs could grind 12 times more grain than before (approx. 36 kg).

In the 6th century BCE, the first primitive mills were used:

- crane mill – top stone attached to a trunnion rotating beam; pushing and pulling alternately the free end of the beam moved the upper stone along the lower one in an arc;

- roller mill – the upper cylindrical stone was rolling on the lower stone; good for pressing oil, not effective for grinding grain.

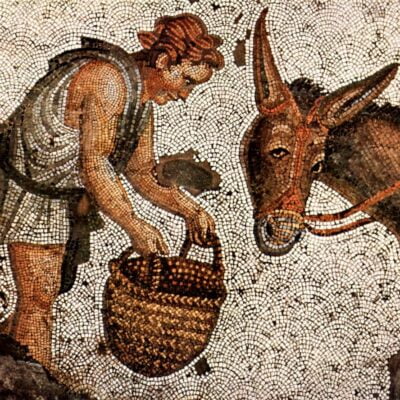

Eventually, rotary mills were created, which took the hourglass shape, where the lower, stationary stone had the form of a cone, and the upper cylindrical one was hollow from the bottom according to the shape of the lower stone, and from the top, it had a second conical hole through which the grain was poured. A special wooden pivot in the centre of the “hourglass” made it possible to adjust the clearance between the stones, which made it possible to obtain the desired fineness of the flour. The horizontally protruding spokes of the capstan allowed the stone to rotate around its axis. The driving force of the mill was the donkey or, more often, the slaves, because the bad construction of the harness used in those days (around the animal’s neck) and the usually too short capstan arms made the donkey’s work extremely inefficient – in the end, the use of slaves was cheaper.

In the 2nd century BCE, Philo of Byzantium described the principle of operation of the backwater and hopper water wheel. At the end of the Republic, the water wheel became widely used for lifting water (tympanum, bucket wheel, Archimedean screw) and for grinding grain. Evolution was a combination of the principle of a mill and a water wheel (the first mentions of water mills are found in Strabo around the 1st century BCE) using a toothed gear.

Three basic types of water mill drive were used:

- horizontal wheel – the simplest structure, not requiring a gear, the water wheel and the millstone were connected by a rigid beam; very inefficient, only suitable for rapid current use;

- drive wheel – requiring the use of gear, inefficient; the large mass of water required with a lazy river current;

- seed wheel – as above, much more efficient, necessary water drop equal to at least the height of the mill wheel.

The use of a grain mill allowed the grain to be ground on a large scale. Around 170 BCE, the profession of a baker was introduced in Rome. Documents from CE 200 describe a mill with a set of 16 mill wheels near Arelate, possibly with feed wheels. In the 4th century CE in Gaul, a similar principle was used for sawing marble blocks. In the 6th century CE, water mills were probably the only source of flour production in Rome.