Chapters

The birth of a child was an important event in every culture. The birth of a healthy and strong offspring, who will bring pride to his family and ensure its continuity, has always been eagerly awaited. However, childbirth was associated with great danger and the threat of death or serious illness not only for the mother but also for the child.

Ancient doctors left behind works from which we can find out how the preparations for childbirth lasted and how the childbirth itself proceeded. They give examples of folk beliefs and superstitions that were supposed to help a woman in labour relieve pain, and describe the tasks of a midwife.

Pliny the Elder, a Roman polymath of the 1st century CE, in his “Natural History”, book VII on anthropology and human physiology, describes various methods of accelerating and facilitating childbirth. According to him, it is much easier to give birth to a boy than a girl. Vapours emanating from hyena blubber cause immediate labour. Placing a hyena’s right paw on a pregnant woman will make childbirth easier, while placing a hyena’s left paw may cause death. A drink mixed with powdered sow’s dung relieves pain, as does sow’s milk mixed with honey. Childbirth will be easier if the woman drinks a decoction containing goose semen mixed with water or “liquid that flows from the weasel’s uterus”. Pliny also mentions medicines made from herbs and various plants. Verbena root was valued for its strengthening and calming properties; scordotis (tencrium scordium), a plant related to garlic, had antiseptic properties; oregano or Diptam leaves (origanum dictamnus) had mint-like properties. Various items and protective amulets were also used during the postpartum period. It was believed that tying a snake moult on the thigh of a woman giving birth would help her quickly recover and recover from an exhausting childbirth.

We do not know whether the above-mentioned measures and practices were effective. We can guess that the presence of items such as snake skin in the room of a woman giving birth posed a risk of infection for both the mother and the newborn, especially when these items came into contact with the intimate parts of the woman in labour. But nevertheless, we must appreciate the potential placebo effect of these items. If a woman believed that a certain thing relieved pain and made childbirth easier, she could relax more and feel better.

Soranus of Ephesus, a Greek physician living in the 2nd century CE, in her work Gynaikeia (“On Women’s Matters”) in four books deals with the duties of a midwife and the hygiene and care of infants.

In the first book, we can find a description of the ideal midwife. According to Soranus, the woman giving birth should be a professional and have high competencies. The author adds that many women do not meet these basic criteria. I’m writing:

It is necessary to reflect on this question so that we do not toil in vain and teach unfit people. Knowledge of writing, reason, good memory, diligence, honesty are needed, in general it must be distinguished by keen senses, be free from all disabilities and strong. As some add, she should have long narrow fingers with small and rounded nails. The knowledge of writing gives her the possibility of theoretical training in craftsmanship. The intellect facilitates his understanding of what he hears and sees, and by a good memory he can retain what he has learned, for knowledge arises from retention and conception. Love of work and perseverance go together; and perseverance is needed to get acquainted with such material. Honesty is needed, because it will be entrusted in the future with the farm and the secrets of life, and because people of bad character, who know about medical matters, can misuse them. A midwife must have acute senses, because she must look at it, listen to it with her ear, and examine it by touch. She dare not be burdened with any disability, so that she can perform her actions cleverly. She must be strong, because by moving from place to place she works double. The fingers should be long, narrow and with short nails, so that when touching the internal parts in a state of inflammation, they do not increase it. This, indeed, is all achieved by taking things seriously and practicing.

In Soranus we find a mention that obstetrics was not reserved exclusively for midwives. A doctor, a man, in exceptional situations could also deliver childbirth. However, the sources leave no doubt that delivery was mainly done by midwives.

In some parts of the Mediterranean, especially in the Greek-speaking part, the profession of midwife (maia) was distinct from that of midwife (iatros gynaikeios). What’s more, this profession enjoyed great respect and gynaecological treatises were written in these areas by women with Greek-sounding names. Often fragments of these works were quoted in the works of ancient physicians. In the Roman West, the situation was somewhat different. Of the thousands of epitaphs collected in the CIL, only sixteen are dedicated to the memory of deceased women who were midwives. Of these inscriptions, nine come from the columbaria of the great Roman patrician families or belonged to the familia Caesaris. The conclusion is that large and wealthy families had their own midwives. Only one inscription indicates that the deceased woman was a slave; the other women were freedmen or daughters of freedwomen. From this, it follows that midwives were very valuable – so much so that they were offered freedom.

We do not know what criteria were used to select slaves who were to become midwives. It was probably the mothers who taught the daughters or the slaves who became the apprentices of the home midwives. Despite the very scant evidence on how midwives were selected and trained, it seems reasonable to say that most of the women trained came from the eastern Mediterranean, where the profession was more respected and had a longer tradition than in the west. The services provided by midwives were not the cheapest. In the comedy Plautus (3rd-2nd century BCE) The boastful soldier (Miles Gloriosus) one of the heroes, Periplectomenus laments the audience by saying that women always want more money – even the midwife, who did not agree to the amount he proposed. In a marriage contract from the mid-3rd century BCE found in Oxyrhynchus, Egypt, the wife stipulated that when she became pregnant and therefore separated, the husband had to give her 40 drachmas. This sum probably includes not only the midwife’s services but there is no doubt that the greater part of it was payment for her services. In “Gynaikei”, Soranus admonishes midwives not to be greedy for money: “[the midwife] dare not be greedy lest she spends fetuses for money.” There is no doubt that the majority of society could not afford the services of a professional midwife. Soranus mentions that there were more or less educated women who gave birth. Presumably, poor families turned to the sagae, the wise women that Rome was full of, or to any female relatives who could do anything they could to help during childbirth.

Later in his work, Soranus gives us a description of the equipment that every midwife should prepare and use during childbirth. And so:

olive oil [clean, unused for cooking], hot water, warming ointment, soft sea sponge, a few pieces of woolen cloth, bandages [to wrap a newborn ], incense [various fragrances: barley, apples, lemons, melons, cucumbers], a stool or a birthing chair [this was the most important element of the midwife’s equipment: she had to bring it to the house where she gave birth], two beds [hard, which was used in preparation for the actual birth and soft – for postpartum rest]and the right room [the room should be of medium size and temperature moderate].

Soranus gives a precise description of the chair on which the woman gave birth. Both midwives and doctors believed that delivery would go more smoothly when the woman was in a sitting position. There was a crescent-shaped hole in the seat of the chair, through which the newborn would come out. There were armrests in the shape of the letter PI on both sides, which the woman in labour clutched. The chair had a strong backrest so that a woman could lean against it with her hips and buttocks. Soranus suggests that some chairs had no backrest; one of the attendants stood behind the woman in labour and held her up.

The sides of the chair on which it stood were closed, while the front and back were open to allow and facilitate the work of the midwife. If for some reason a birthing chair was not available, the woman in labour would sit in the lap of another woman who, understandably, had to be strong enough to lift and hold the woman in labour. From this, we can conclude that in families that could not afford to pay for a midwife, births took place in a similar way.

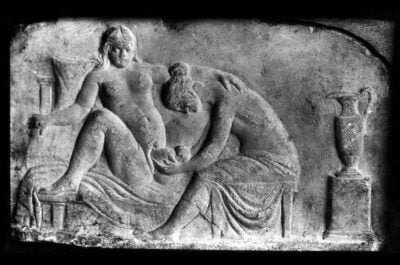

Preparations for the actual birth were made by the woman in labour lying on her side on a hard, low bed with her hips supported, her feet together and her thighs apart. To ease the pain, the midwife gently massaged the mother-to-be. A cloth soaked in hot oil lay next to the belly and near the genitals of the woman in labour, and on both sides of her were animal bladders filled with hot oil. When cervical dilation occurs, the midwife accelerated the process by gently rubbing the dilation with the oiled index finger of her left hand. When the dilation reached the size of an egg, the woman in labour was transferred to a chair. The most important thing was timing the transfer of the increasingly weak woman; if she was too weak, the birth took place on a hard bed.

In fact, the midwife did not deliver herself. She was assisted in this by three more women who stood to the sides and behind the birthing chair. Soranus explains that the assistants were supposed to calm the woman in labour. Assistants standing on the sides of the chair gently pressed the belly of the woman in labour to speed up the birth. The woman behind the chair had to be strong enough to hold the woman in labour. The midwife, dressed in an apron, sat opposite the woman in labour and watched over the proper course of the delivery. There is no evidence that an episiotomy was used when there were problems with the normal expulsion of the fetus from the uterus during delivery.

One of the most important duties of the midwife was to instruct the woman in labour at what pace she should breathe and how she should push. Pliny the Elder in “Natural History” expresses the opinion that a woman who cannot properly control the rate and depth of breathing may have problems during childbirth. However, choking can have fatal consequences.

In the case of normal delivery, when the baby’s head appears first, the midwife enlarged the dilation by positioning the baby’s head and shoulders, and then gently remove them. At the same time, she had to be very careful not to overstretch the umbilical cord. Immediately after the birth of the baby, she gently removed the placenta. In his work, Soranus instructs midwives to wrap their hands in fabric or thin papyrus just before the climax of childbirth. She explains that such a procedure will prevent the newborn from slipping out of the embrace and will protect it from inadvertent and too-strong squeezing by the midwife.

In the further part of Gynaikei the author draws attention to the fact that the state of mind of a woman giving birth is very important for the course of childbirth. She advises that the people delivering the child put a lot of work into the proper mental preparation of the woman in labour, calms her down, soothes her nerves and dispel her fears. When a woman in labour suffers from excessive “sadness, joy, anger or over-indulgence” childbirth is sure to be difficult. Soranus adds that inexperienced women cause more birthing problems and have a harder time than those who have given birth before. The same is true of women who did not believe they were pregnant; they are also having a hard time with childbirth.

When the baby was born, the midwife’s task was to check its health. In the beginning, she checked the newborn baby for any visible birth defects. Soranus gives a number of examples of how to check the health of a newborn:

Then, the child should shout loudly as soon as he is placed on the ground. If it does not cry for a long time, or only cries a little, then it raises the suspicion that something bad has happened to it, or that it is suffering. All parts of the body, limbs, and senses should be in good condition, and the openings, such as the ears, nostrils, larynx, urethra, and stool opening, should be free; the movements of each joint should be correct, not sluggish and weak, as should the ability to bend and straighten the limbs, the size, shape and feeling, which we know by pressing with the fingers; because the physiological symptom is pain when struck or kneaded. A child who behaves to the contrary is unfit to be brought up.

It was probably the midwife, based on her own experience, who assessed the newborn’s chances of survival. The ancient Romans generally recognized the necessity of natural feeding of infants with human milk by a natural or surrogate mother. Pliny the Elder wrote that the best food for a child is the milk and care of the natural mother. Soranus, on the other hand, justified feeding a newborn with mother’s milk on the grounds that mothers love their children more and have appropriate physiological conditions:

Among other equal conditions, it is preferable to feed the newborn with mother’s milk. This is more appropriate, and for that reason, because mothers like their children more. In addition, it corresponds more to physiological relations if the mother, like before the birth, also feeds the child after it.

How long was the time of leaving children at the mother’s or wet nurse’s breast? In medical and literary sources, as well as legal documents, among the comments on the hygiene and diet of a child, we find information about the length of breastfeeding. The famous Roman poet Lucretius, who lived in the 1st century BCE, suggests that babies need their mother’s milk until they are three years old. He writes: “(…) a lively horse blooms after three round years, but not a boy. Often even then he will look for the milky bulges of his breasts in his sleep.”

A similar view can be found in the Roman writer Quintilian (1st century CE), who, following the philosopher Chrysippus, writes about the care of mothers over children: “Thus, for example, Chrysippus, although he gave three years to nurses, believes that already they, too, are to mold the child’s soul.”

In turn, in medical sources we find information that an infant can be weaned after 6-7 months of life, i.e. when the child begins to get the first teeth and can start eating solid food:

As soon as the body is strengthened and able to take solid food – which, however, does not happen before six months – it is appropriate for that time to give the child flour foods (…). At this time, when the child already willingly eats flour and when the growing teeth suggest the possibility of crushing solid food – which usually takes place around the third or fourth six months – then you need to carefully and slowly wean him from the breast and from milk by giving him more and more food., and by reducing the amount of milk.

In his work, Soranus orders wet nurses to abstain from sex while breastfeeding for fear of losing milk and becoming pregnant:

We demand moderation from the nurse, abstaining from coitus and wine, and getting rid of lewdness, all other pleasures and licentiousness. Coitus spoils the milk, and besides the fact that by lovemaking the love for the child is diminished, it reduces its quantity and causes its atrophy by stimulating it to regularity or causing it to be replaced.

It is likely that such views had a direct impact on the recommendations for wet nurses in infant feeding contracts. These documents, written on papyri and originating from Greco-Roman Egypt, established the conditions of childcare, including the length of the breastfeeding period, the amount of payment and information on the need to maintain sexual abstinence during the breastfeeding period. An example of this is the text from papyrus BGU 1107, in which we read that as long as the wet nurse is paid, she must take care of herself and the child, not spoil the milk, not sleep with a man and not become pregnant.

The view that the milk of a menstruating wet nurse is bad for the child has survived in medicine and moral culture for quite a long time. The constant concern to avoid a new pregnancy, which forced the interruption of breastfeeding, seems to be one of the most important motives for sexual restrictions for nursing women, mainly for mothers, which became a certain taboo. This opinion can still be found in 19th-century medical texts.

Diseases

All in all, the knowledge of diseases was extensive and consisted of the developed art of groping. Soranus described shaking and percussion of the lower abdomen and used a rich set of instruments in his research. treatment of infertility, menstrual disorders and inflammation of the uterus was dealt with. The gynaecological diseases described by Soranus were adequately treated.

Much has been written about strictures in the female genital tract. Discs or surgery were recommended. Changes in the position of the uterus were studied. The prolapsed uterus was removed manually or by turning the affected uterus upside down. Discs were also used. The beginnings of surgical treatment of uterine prolapse are described in Hippocrates and Celsus. Soranus considered inflammation to be the cause of uterine bends. women’s hysteria (Greek hystera uterica) was associated with uterine displacements and wanderings. Gynaecological drugs included suppositories that acted mechanically or chemically, they were also inserted into the uterus. Sid baths, fuming, ingots and rinsing were used. The contraceptive measure for Hippocratic “bowls” was a bean-sized iron-containing mineral inserted into the uterus. Soranus recommended closing the opening of the uterus with a ball of cotton with ointment or sour oil. In the writings of the Hippocratic, in the so-called doctor’s oath, was the phrase “Likewise, I will never give a woman a fetus abortion suppository.” There were no laws against abortion, however. This attitude was more ethical. In antiquity, especially towards the end, contraception, abortion and infanticide increased.

Abortion-inducing agents were exceedingly numerous. Professional poisoners spent their fetuses in Rome. Obstetrics and gynaecology were mainly dealt with by midwives. Hippocrates had a certain fear of touching the female genitals. The doctor gave orders, but the examinations were carried out by the midwife, who, thanks to her cooperation with the doctor, was quite well-educated. Hence, in Soranus’ work on obstetrics and women’s diseases, there are provisions about the physical and spiritual qualities of midwives at the beginning. They should know fisticuffs, dietetics and therapy, but they didn’t need to know about body parts. They shouldn’t give birth on their own anymore. They should sympathize. At the end of his work, he summarized it in questions and answers. In the 6th century CE, this text was translated from Greek into Latin by Mustio and, together with fetal position engravings, was widely distributed throughout the Middle Ages. Soranus himself had to overcome prejudices related to the predominance of women in practising this speciality. He excluded mystical views. He is considered the great gynaecologist of antiquity. His surgery is lost while gynaecology is known. It was the pinnacle of ancient, methodical obstetrics and gynaecology.

Finally, it is worth noting that maternal mortality was high. It was mainly due to the lack of appropriate medical knowledge, lack of medicines and lack of knowledge about the need to maintain sterility.

Among the famous Roman women who died in childbirth are:

- Julia Cornelia (104 BCE) – wife of Lucius Cornelius Sulla

- Cornelia (69 BCE) – wife of Julius Caesar

- Julia (54 BCE) – daughter of Julius Caesar

- Tullia (45 BCE) – daughter of Cicero

- Junia Claudilla (1930s CE) – first wife of Caligula

- Galla (394 CE) – wife of Theodosius I