Chapters

War in 189 BCE between the Roman Republic and the Galatians, Gauls inhabiting Asia Minor. The pretext for the war was the fact that the Galatians provided armed reinforcements to the Seleucids, and their warriors even fought against the Romans in the Battle of Magnesia.

Background of the conflict

In 191 BCE, Antiochus III the Great, ruler of the Seleucid Empire, invaded Greece. The Romans decided to intervene and defeated Antiochus in the Battle of the Thermopylae. The defeated Seleucids retreated back to Asia Minor, while the Romans, along with their Pergamon allies, pursued them and eventually defeated them in the Battle of Magnesia.

The defeated Seleucids were forced to sign a peace treaty with Scipio of Asia, ending the war with Rome. In the spring, a new consul, Gnaeus Manlius Vulso, arrived in Asia Minor to take control of Scipio’s army and to complete the signing of the peace treaty negotiated by Scipio. Vulso, however, was not satisfied with the task entrusted to him and began to plan a new war. During the meeting with the soldiers, he praised them for their bravery and congratulated them on the victory over Antiochus, and also proposed an attack on the Galatians, Gauls inhabiting Asia Minor. The pretext for the war was the fact that the Galatians provided armed reinforcements to the Seleucids, and their warriors even fought against the Romans in the Battle of Magnesia. The legionaries eagerly agreed to the consul’s proposal.

The consul arrived in Ephesus in the beginning of spring, and, having taken over the troops from Lucius Scipio and purified1 the army, he delivered a speech to the soldiers in which he gave great praise to their valour because they had ended the war with Antiochus by a single battle, and urged them to undertake a new war with the Gauls, who had not only aided Antiochus with auxiliaries but possessed spirits so untamable that the expulsion of Antiochus beyond the ridges of the Taurus mountains would be in vain unless the power of the Gauls were broken, while as regards himself also he added brief remarks, neither false nor exaggerated.

– Titus Livius, Ab urbe condita, 38.12

In reality, however, Vulso wanted the fame and wealth of the Galatians who had gotten rich by plundering the neighbouring lands.

This war was the first time in Rome’s history that a general started an armed conflict on his own initiative, without obtaining the prior consent and approval of the senate. In the future, this type of incident happened several more times.

Consul Wulso began preparations for the war, calling for help from the Pergamon army. Although the king of Pergamon, Eumenes II, was currently in Rome, his brother Attalus II, who was regent, joined the Roman army with a force of 1,000-foot soldiers and five hundred horsemen.

March into Asia Minor

A combined Roman-Pergamon force marched out of Ephesus and, after crossing the Meander River, entered the territory of Alaband, where they met Attalos’ brother Athenaeus, who joined the allied army with 1,000-foot soldiers and three hundred cavalry. Then the entire army marched to Antioch, where they met the son of Antiochus, Seleucus, who, as part of a peace treaty, provided the Romans and Pergamon with grain.

Allied forces then marched through the upper valleys of Meanderu and Pamphylia, collecting tribute from local kings and tyrants who dared not oppose the powerful Roman-Pergamon forces. Finally, they entered the territory of Kibyra, ruled by the cruel tyrant Moagetes, who sent envoys to the Romans asking them not to destroy his country, for he was always a friend of Rome. By the way, as an act of goodwill, he offered Vulso a wreath worth fifteen talents. The consul, however, was not very friendly towards the tyrant:

When Gnaeus Manlius Vulso, the Roman consul, approached Cibyra and sent Helvius to find out what the mind of Moagetes was, the latter sent envoys begging Helvius not to lay the country waste as he was the friend of the Romans and ready to do anything they told him.

– Polybius, The Histories, XXI.34

The MPs were appalled by this type of response and urged the consul to meet the tyrant personally, to which Vulso agreed. The next day, Moagetes left the city at the head of a modest retinue and offered the consul fifteen talents in exchange for leaving his lands. However, Gnaeus was not thrilled with this proposal:

Manlius, amazed at his impudence, said not another word, but merely that if he did not pay five hundred talents and thank his stars, he would not only lay waste his territory, but besiege and sack the city itself.

– Polybius, The Histories, XXI.34

The tyrant was terrified by the threats and demands of the Romans, but he was able to bargain a ransom of up to a hundred talents and ten thousand medimals of wheat. When the consul crossed the river called Kolobatos with his army, he met with envoys from the city of Sinda. The deputies asked him to help in the fight against the Termesses, who had invaded their lands and besieged the fortress where all their citizens had taken refuge, including their wives and children.

The consul agreed to the deputies’ offer and marched to the land of the Termesses, with whom he made an alliance in exchange for fifty talents and withdraw from Sindian territory. Then Vulso marched on the city of Kyrmasy, which he captured and plundered, gaining enormous loot in the process. Meanwhile, he received tribute from the envoys of the city of Lisynoe, and then plundered the land of the Sagalassians, who finally made peace with it at the cost of fifty talents and twenty thousand medimals of wheat and twenty thousand medimals of rye.

The consul then reached the Rotrin Springs, where he met Seleucus again. Seleucus took a convoy with him to Apamea with wounded and sick Roman soldiers and some of the loot. He himself left the Romans guides to lead them on their further march. Three days later, the Romans reached the lands of the Tektosaga, one of the three Galatian tribes. The consul called a conference, during which he informed the soldiers about the upcoming war. Then he sent envoys to the leader of the Tectosagi, Eposognathus, who was the only one to maintain friendly relations with Pergamon. The envoys soon returned, bringing a response from the chief who pleaded with the Romans not to attack his lands. He also proposed that he himself could persuade other chiefs to obey the consul.

The Roman army advanced deep into Galatian territory and established a camp near the Galatian fortress, Kuballon. Here the first armed confrontation with the Galatians took place:

While the Romans were encamped near Cuballum, a fortress of Galatia, the enemy’s cavalry appeared with great uproar, and not only threw the Roman outguards into confusion by their unexpected attack, but even killed some men. When this disorder was reported in the camp, the Roman cavalry, pouring in haste from all the gates, repulsed and routed the Gauls and killed a considerable number in their flight.

– Titus Livius, Ab urbe condita, 38.18

This clash made the consul understand that the enemy was nearby. From then on, he decided to proceed with more caution and to ensure proper reconnaissance and reconnaissance.

Battle of Mount Olympus

A few days later, the Roman-Pergamon army reached the city of Gordion, which was abandoned by the inhabitants. When they set up camp, a messenger from Eposognatoas reached them, informing the allies that the attempt to persuade the other Gatans leaders had failed and that they themselves were going to fight against the Romans:

While he was maintaining a base there, ambassadors from Eposognatus came reporting that his visit to the chiefs of the Gauls had won no fair response; from the villages and farms in the plains they were moving in large numbers, accompanied by their wives and children, driving ahead of them and carrying what they could carry and drive,6 and were making for the Olympus mountain, that thence they might maintain themselves by arms and by the situation of the place.

– Titus Livius, Ab urbe condita, 38.18

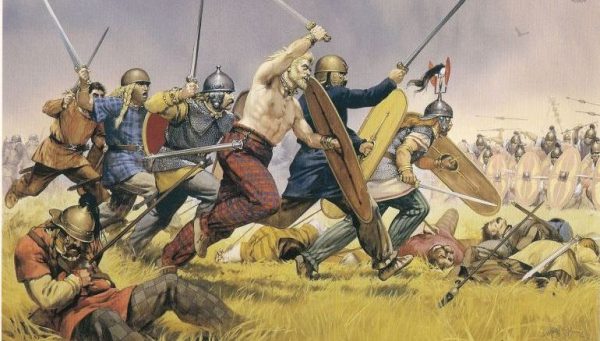

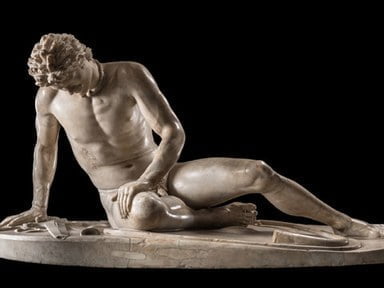

Meanwhile, the Tolostobogi tribe took Mount Olympus (now Mount Uludağ in Turkey). The Tectosags removed Eposognathus from power, for his relations with the Romans, they took Mount Magaba. In turn, the Trokma tribe left the women and children under the care of the Tektosagi, and the warriors marched to the relief of the Tolostobogs. The Galatians on Mount Olympus built fortifications with the intention of defending against the enemy. For the first two days, the Romans limited their activities to reconnaissance, engaging in minor skirmishes with enemy cavalry, and on the third day, they launched their final attack. The battle was started by the Roman Velites, who showered the Galatians with javelins and slingshot projectiles, inflicting heavy losses on them. Then there was hand-to-hand combat, in which the Roman legionaries, better armed and organized, quickly took over the Galatians. The battle quickly turned into slaughter, especially when the Romans entered the enemy camp. The Galatians lost no less than ten thousand killed in the battle, and about forty thousand were taken prisoner. After the battle, consul Vulso ordered some of the weapons captured by the enemy to be burned, and the rest was sold or distributed among the legionaries.

Battle of Ankyra

After the Roman victory at Mount Olympus, the Tectosags sent envoys to the Romans with a proposal to meet and discuss peace conditions. The meeting point was to be halfway between the Roman camp and the city of Ankyra (today’s Ankara). In reality, however, the Galatians played for time, as they wanted to allow their women and children to escape across the Halys River, and the meeting itself was in fact an attempt on the life of Consul Vulso. When the Romans went to the meeting, they were attacked by a large detachment of Galatian cavalry. A fight close to the hair would have ended tragically for the consul, if not for the relief of the Roman cavalry, which was just nearby, as an escort of foragers, gathering food and fuel for the army in the area.

The attempted assassination of the consul sparked rage among the Romans and a thirst for revenge. Without a moment’s delay, they broke camp and marched towards Ankyra, where the tribes of Tectosaga and Trokma had gathered their forces. As before, the Romans will spend the first two days exploring the entire area. On the third day, after sacrificing to the gods, the consul set out with his army against the forces of the Galatians, which numbered about fifty thousand men. As before, the first Roman velites attacked, inflicting heavy losses on their enemies, after which the hand-to-hand combat began. The Galatians, distracted by their earlier failures, quickly allowed themselves to be distracted and then began to flee. The Romans gave chase, but fortunately for the Galatians, the legionaries preferred to focus on plundering an abandoned enemy camp rather than chasing the fugitives, and most of them managed to cross the Halys River and join the women and children. The victors of the Romans took enormous spoils in the battle:

The next day he surveyed the prisoners and booty, which was as great as a people most greedy for plunder could amass after holding under armed control for many years everything on this side of the Taurus mountain.

– Titus Livius, Ab urbe condita 38.27

End of the war

Both lost battles completely broke the morale of the Galatians, who felt it was best to make peace with Rome. The victorious campaign, in turn, enriched Vulso and his soldiers greatly, as they fell into the hands of the riches of the Galatians, which they had acquired by plundering Asia Minor. The Galatians sent envoys to the consul asking for peace, but he told them to come to the talks in Ephesus, as he himself, due to the coming winter, was going to retire to the coast and spend the winter there.

Consul Vulso stayed in Asia Minor for another year, during which he signed a peace treaty with Antiochus, and also divided land on the coast of Asia Minor between Pergamon and Rhodes. When the Galatians’ legation reached Ephesus, Vulso ordered them to wait for the return of King Eumenes from Rome, who was to dictate the terms of peace. The victory over the Galatians themselves caused great enthusiasm among the inhabitants of Asia Minor, who from then on had to fear their invasions:

And while the Roman victory over King Antiochus had been more glorious and more splendid than that over the Gauls, yet the victory over the Gauls afforded the allies more satisfaction than that over Antiochus. The slavery imposed by the king was more endurable than the ferocity of the rude barbarians and the constant and uncertain fear as to whither a storm so to speak would bring the Gauls marauding upon them.

– Titus Livius, Ab urbe condita, 38.37

Vulso began his journey back to Rome in 187 BCE and finally made it there a year later. Upon his return, he faced a wave of criticism from the Senate for having arbitrarily unleashed an armed conflict without obtaining prior consent. The senators even went so far as to deny Vulso the right to the triumph he had legally owed for his victory. Ultimately, however, thanks to the intercession of family, friends and distinguished citizens of Rome, Vulso was able to refute these arguments.