Agrippina the Younger, also known as Julia Agrippina, was the daughter of Germanicus – an excellent Roman commander and Agrippina the Elder – an energetic and brave woman.

Agrippina the Younger was born in about 16 CE in the city of Oppidum Ubiorum (current Cologne). It was a city located on the Rhine, inhabited by Germanic tribes. There was the headquarters of her father’s Germanic army. The city of Ubii, in 50 CE was named COLONIA CLAUDIA ARA AGRIPPINENSIS. This husband’s official name was – on Agrippina’s initiative – her husband Emperor Claudius. This city exists to this day and is called Cologne.

Agrippina the Younger lived under the following emperors: Tiberius (her uncle), Caligula (her brother), Claudius (her husband) and Nero (her son). These were the years when the power struggle in the Roman Empire was brutal and always brought to the fore. Agrippina the Younger also participated in these fights from an early age, who, like others, was unscrupulous in her pursuit of her goal.

Agrippina the Younger spent all her childhood with her siblings alongside her mother and father, traveling all the time.

Her husband at the age of twelve was Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus, who came from a great family of Domitius. He was fifteen years older than Agrippina the Younger and enjoyed a terrible reputation. According to Suetonius, Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus was a man “whose whole life was condemnable in every respect. (…) For example, in a settlement on the Apian road unexpectedly he galloped with his team and without any scruples, consciously drove the boy. In Rome, in the middle of the forum, he forged a knight’s eye for arguing with him too freely”1. From this relationship, the later Roman emperor – Nero was born. After the birth of his son, when his friends congratulated him, he replied that “from a relationship like him and Agrippina, only something very wicked and fatal to the state could be born”2. Gneaus Domitius Ahenobarbus was accused at the end of the reign of Emperor Tiberius of insulting majesty and adultery with his sister Lepida. He avoided punishment by changing the ruler. “He died in Pyrgi because of water ascites”3.

From February 37 CE, when the emperor Caligula, her birth brother, Agrippina the Younger, and her younger sisters, Julia Liwilla and Julia Druzylla, took an honorable position in the state, and at the same time they were at the decadent court of Caligula. Accused of participating in a plot to kill her brother, then Emperor Caligula, she was sent to exile on the island of Pantea and her sisters.

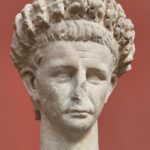

After the death of Emperor Caligula, the brother of Agrippina the Younger, Claudius, Germanicus’ brother, became the new emperor of Rome. His coming to power was described in his work by Suetonius:

Having spent the greater part of his life under these and like circumstances, he became emperor in his fiftieth year by a remarkable freak of fortune. When the assassins of Gaius shut out the crowd under pretence that the emperor wished to be alone, Claudius was ousted with the rest and withdrew to an apartment called the Hermaeum; and a little later, in great terror at the news of the murder, he stole away to a balcony hard by and hid among the curtains which hung before the door. As he cowered there, a common soldier, who was prowling about at random, saw his feet, intending to ask who he was, pulled him out and recognized him; and when Claudius fell at his feet in terror, he hailed him as emperor.4

By assuming imperial power, Claudius sought to maintain the seriousness of his own family, “instituted his most holy and most common oath: in the name of Augusta”5. He gave his deceased father Nero Claudius Drusus, brother of Tiberius, and mother Antonia the Youger funeral ceremonies at the expense of the state, and each of them separately the annual circus games on their birthday. He awarded prizes to praetorians and canceled newly introduced taxes.

At the beginning of his reign, Emperor Claudius also announced an amnesty. He dismissed from exile, among others Caligula’s sisters, Liwilla and Agrippina the Younger. In addition, on the initiative of Claudius, the former owners were also confiscated, the slaves of the informers were punished. Placing trials for contempt of majesty was forbidden.

Despite the attempts to rehabilitate Claudius recently in science, the view is rather maintained that he was an infirm ruler, influenced by the environment, especially his notorious wife Messalina, later Agrippina6.

Agrippina the Younger, immediately after returning from exile to Rome, began to develop lively activity. In this way, she tried to compensate herself for two years in exile. Above all, however, she wanted to pave the way for her son Nero to take the throne.

Agrippina the Younger decided to get her husband quickly, thanks to whom she would be able to achieve her goal. Her first husband, Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus, died when Agrippina was in exile, as I mentioned earlier. Agrippina the Younger, Sulpicjusz Galba, seemed to be the best candidate for marriage at that time, who had an excellent reputation. It was him who tried to convince Agrippina the Younger to marry. This was during the lifetime of his first wife Lepida. “Until at one women’s meeting she was sharply insulted verbally and even actively by Lepida’s mother”7. After this incident, Agrippina the Younger gave up the capture of Galba. Soon her next batch hit her. He was Valerius Crispus, widowed after the death of Domitia, the sister of her late husband: a two-time consul, an excellent speaker, a great lover of trees, almost an ecologist at that time, a rich man8. After the wedding, Valerius Crispus made her and her son Nero his heirs because he had no children. He died, as was commonly believed, prematurely and precisely because of her.

Agrippina the Younger had to be very careful for many years after returning. At any moment she and her son were in danger of mortal danger from Messalina – the wife of Emperor Claudius. Valeria Messalina was the third wife of Emperor Claudius. According to Valeria Messalina, “as an empress, she showed up in public at night in a brothel with blond hair dyed and exposed breasts painted golden”9. It was Messalina who tried to remove little Nero, because she was afraid that with the help of her mother Agrippina the Younger, in the future he could become a rival to the power of her son Britannicus.

Agrippina waited patiently for the fall of Messalina, winning one of Claudius’ very influential freedmen, Pallas. Pallas was a slave to Antonia – the mother of Emperor Claudius, who liberated him. He was Messalina’s mortal enemy. Pallas was, according to A. Krawczuk, and rationibus – “from accounting”10.

The death of Messalina opened a new marriage perspective for Agrippina the Younger and a chance to implement a plan that was to bring her closer to power. Therefore, she decided to fight for a place alongside Emperor Claudius. She had two rivals: Lollia Paulina and Elia Petyna. Thanks to the skill of her friend Pallas, Agrippina the Younger won other candidates for marriage with the emperor Claudius. So “after Messalina, Claudius married his niece Agrippina the Younger, the patron of COLONIA AGRYPPINENSIS, the city of Cologne”11 as the fourth wife. According to Tacit, “Pallas mainly praised in Agrippina that she would bring with him a grandson of Germanicus; it would be by all means worthy of an imperial height to attach this noble branch to the descendants of the Julian and Claudian families”12. In addition, Agrippina the Younger was a beautiful woman, and Claudius, according to sources, had a weakness for women with a strong personality. The final decision of Claudius, apart from Pallas’s words, was influenced by Agrippina’s personal efforts. “She, often visiting her uncle under the guise of kinship, seduced him so much that she had priority over others and not being yet – the wife already had the power of his wife”13. In turn, A. Krawczuk claims that the decision of Emperor Claudius was influenced by the fact that Agrippina the Younger was his relative and the closest of the living. He justifies it by the fact that “the emperor, terrified of constant intrigues and betrayal at home, wanted to have a woman at his side whom he could trust without reservation”14.

In my opinion, all these factors influenced the decision of Claudius, both Pallas’s persuasion, seductive efforts of Agrippina the Younger, and kinship with the emperor.

And this time it was not without obstacles – Claudius was the brother of Germanicus, father of Agrippina the Younger, and therefore her uncle. This obstacle, in the form of a relationship that was too close, subject to the charge of incest in Rome, was finally removed by a Senate resolution. According to Suetonius, Agrippina “daughter of his brother Germanicus, aided by the right of exchanging kisses and the opportunities for endearments offered by their relationship; and at the next meeting of the senate he induced some of the members to propose that he be compelled to marry Agrippina, on the ground that it was for the interest of the State; also that others be allowed to contract similar marriages, which up to that time had been regarded as incestuous”15. Agrippina, Lucius Vitelius, helped in settling this matter. He, having made sure that Emperor Claudius would submit to the resolution of the Senate, led the case. As Tacitus says: “Members were not lacking to rush from the curia, with emulous protestations that, if the emperor hesitated, they would proceed by force. A motley crowd flocked together, and clamoured that such also was the prayer of the Roman people. Waiting no longer, Claudius met them in the Forum, and offered himself to their felicitations, then entered the senate, and requested a decree legitimizing for the future also the union of uncles with their brothers’ daughters”16. At the same time, Agrippina the Younger sought to obtain the consent of Emperor Claudius to marry his daughter Octavia with her son Nero. It was not easy, because Octavia was engaged from an early age with Silanus. After a short time, Sylanus was slandered before Claudius, expelled from the senate and removed from office. On the wedding day of Agrippina the Younger and Claudius, Sylanus committed suicide, “whether he had prolonged the hope of life until now, or that he had chosen that day to make them hideous”17. Later, Agrippina the Younger managed to lead to the engagement of Nero and Octavia. This time the consul Mammiusz Pollion helped her. “Octavia was engaged, and Domitius, who added his position of fiancé and son-in-law to his previous affinity, became equal to Briton thanks to the efforts of the mother and the deceit of those who, due to the accusation of Messalina, were afraid of revenge on the part of her son”18.

Agrippina’s next step was to skillfully remove people close to Messalina from the court, and introduce hers. “From then on, the state took a different form: everything was listened to by a woman who did not play with the Roman state as a whim like Messalina, but introduced strict and as if male slavery; she appeared seriously in public, and more often with pride; there was no shame in the house, unless the interest of her power required”19. Agrippina the Younger, not wanting to be known only from bad deeds, “obtained for Anneusz Seneca a release from exile and a pretend, because she thought that it would bring general joy because of the fame of his learning”20.

Anneus Seneca was a great Roman philosopher, writer, rhetorician and poet. He was born around 4 BCE in Cordoba, died in 65 CE He was the son of the rhetor and historian L. Anneus Seneca and Helwia. Seneca was a philosopher of the Stoic school. He left many moral writings, including “For shortness of life”, “For peace of mind”, “For kindness”, “Moral letters to Lucilius” and many others.

During the reign of Emperor Claudius he suffered a serious defeat. Seneca remained in social relations with Germanik’s daughters. The husband of one of them, Agrippina the Younger, Gajen Pasjen Kryspus, was one of Seneca’s best friends. Through these relations he fell into a network of female intrigues, attracted suspicion and disgrace to Messalina21. He was accused of keeping secret affairs with Julia Liwilla – the youngest daughter of Germanik and Agrippina the Elder. In 41 CE he was convicted by Claudius for adultery and sent to the wild island of Corsica. She dismissed him from exile, eight years later, as I mentioned earlier, Agrippina the Younger, wife of Emperor Claudius. He was then entrusted with the post of Nero’s tutor, because Seneca, who had suffered a lot through Claudius, was thought to be able to teach him moderation and gentleness. By recalling Annaeus Seneca, Agrippina the Younger wanted “that Domitius’ youth should mature under the watchful eye of such a teacher, and both of them could use his advice as to the views of rule”22.

Then Agrippina the Younger dismissed from the function of prefects of the Praetorian Guard two Messalina temples. This function was entrusted to Afranius Burrus, who was henceforth the only prefect of the Praetorian Guard. This situation was presented by Tacitus: “Agrippina, however, did not dare to make final decisions until Luzjusz Geta and Rufius Kryspinus were released from the command of the presidential cohorts, whom she considered devoted to the memory of Messalina and her children. Thus, to assure the wife that ambition among the cohorts two people bring split, and if only one led them, discipline would be more stringent – the command of the cohorts is transferred to Burrus Afranius, a man of great war renown, who, however, knew very well whose will puts them at the head”23.

The nomination of Burrus as praetorian prefect in 51 CE strengthened the position of Agrippina, who was systematically preparing the throne for her son Domicjusz Ahenobarb”24.

In 50 years, with the help of Pallas, who “incited Claudius, that he would take care of the Briton’s state and boyhood with strong support”25, Agrippina the Younger obtained permission from Claudius to adopt Nero by him. Thus, Nero was equated with his real son Britannic. At the age of thirteen, Nero was honored by the Senate, in which “a bill was passed, by which he would pass to the Claudian family and receive the name Nero”26.

And so it happened. With the consent of the senate, Emperor Claudius adopted Nero. From then on, he had the surname Nero Klaudiusz Druzus Germanik. He was showered with honors and privileges. In 53 “at the consulate of Decymus Junius Quintus Haterius, 16-year-old Nero received the wife of Caesar’s daughter, Octavia”27. From then on, he became the son and son-in-law of Emperor Claudius.

Agrippina the Younger, securing the support of the commanders of the Praetorian Guard, and binding her son Nero with the house of Emperor Claudius – she hoped that her power would be consolidated in the future. As the wife of the emperor, Agrippina had the chance to continue her influence as the mother of the emperor. Agrippina the Younger constantly strove to bring Nero to power. Thanks to her efforts, “for the fifth consulate of Tiberius Claudius and for the consulate of Servis Kornelius Orfitus, Nero was given a men’s gown ahead of time to make him seem able to engage in public activities. And Caesar’s senate flattery would gladly step down so that Nero in the twentieth year would take over the consulate, while and as the appointed consul, he had proconsular authority outside the capital and was titled the prince of youth. In addition, gratification was divided on his behalf between soldiers and gifts in kind”28. At every public occasion, Nero’s seniority over Briton was emphasized. People who were kind to Britannia – the son of Emperor Claudius – were removed.

Agrippina the Younger herself, as the wife of Emperor Claudius, enjoyed the most important privileges. She was worshiped in cities of the East, such as Mytilene and Ephesus. As Tacitus says: “The exaltation of her own dignity also occupied Agrippina: she began to enter the Capitol in a carriage; and that honour, reserved by antiquity for priests and holy objects, enhanced the veneration felt for a woman who to this day stands unparalleled as the daughter of an Imperator and the sister, the wife, and the mother of an emperor”29. There is also evidence that Claudius Agrippin’s wife had thrush30. Agrippina Nero’s mother wrote (also – VFŚ.) Diaries, which were later used by Tacitus31.

However, these numerous privileges and honors that Agrippina the Younger received as the wife of Emperor Claudius did not make her too popular at the imperial court. Enemies came to meet her more and more often. Narcissus was one of them. He was a freedman, and also a favorite and secretary of Emperor Claudius, who had great influence in the imperial court. It was he who brought the emperor Claudius closer to Britannia, and thus cooled relations with Agrippina the Younger. Emperor Claudius understood that things had gone too far, that he should repair the damage done to his son Britannicus. As Suetonius tells us: “at the end of his life, he overtly and often showed regret at his marriage to Agrippina and Nero’s son’s sons. (…) Immediately after meeting the Briton, he gave him a warm hug with words of encouragement,” that he would grow and receive a bill from all of deeds. “In addition, he added in Greek:” The one who hurt you will heal you. “As an apprentice, almost a child, he decided to give him a toga, since his physical attitude allowed it, and added:” Let the Roman people finally the real Caesar”32. In the face of such behavior of Emperor Claudius Agrippina the Younger felt threatened.

During the short absence of Narcissus in Rome, caused by his departure for treatment to the town of Sinuessa due to gout pain, Agrippina the Younger poisoned her husband – Claudius. According to Tacitus and Suetonius, Agrippina the Younger poisoned her husband with the agent obtained from the famous poisoner Lokusta, who then mixed in the mushroom dish. The poison Claudius was to be served by one of the slaughters Halotus who brought dishes and had previously tasted them. According to Tacitus, “the poison was poured into a tasty dish of mushrooms, and the action of this remedy, whether due to the bluntness of Claudius or that he was drunk, was not immediately known; at the same time, it seemed, his stomach emptying helped. Agrippina was terrified, and because it threatened its last resort, he did not mind the momentary scandal, but he turns to the cautious physician of the initially initiated Xenophon doctor. He, under the guise of wanting to help the vomiting efforts, was to blow a feather in his throat smeared with violent poison, because he knew that the greatest crimes it starts in danger and ends with the reward”33. According to Suetonius, it is not known by whom the poison was given. “Some say that it was given to him at a feast with priests in the castle by the eunuch Halot, who served as an office tasting dishes. Others that during a home dinner, by Agrippina herself. She gave him poisonous mushrooms, which he particularly served fond”34. In turn, I. Bieżuńska – Małowist writes that “maybe this is all true and maybe one more slander and Claudius died of natural death”35. As you can see, there is no uniform agreement among historians as to who poisoned Emperor Claudius. Some say that Agrippina the Younger, the emperor’s wife, contributed to his death, others that he died a natural death. In my opinion, Agrippina the Younger poisoned Emperor Claudius. His removal opened the way for her son Nero to take power, which was her main goal. To achieve it, Agrippina the Younger prepared for this for several years, as evidenced by her earlier moves.

“In the first place, Agrippina, heart-broken apparently and seeking to be comforted, held Britannicus to her breast, styled him the authentic portrait of his father, and, by this or the other device, precluded him from leaving his room. His sisters, Antonia and Octavia, she similarly detained. She had barred all avenues of approach with pickets, and ever and anon she issued notices that the emperor’s indisposition was turning favourably: all to keep the troops in good hope, and to allow time for the advent of the auspicious moment insisted upon by the astrologers”36.

Emperor Claudius “He died on the third day before the Ides of October in the consulship of Asinius Marcellus and Acilius Aviola, in the sixty-fourth year of his age and the fourteenth of his reign. He was buried with regal pomp and enrolled among the gods”37.

In this way, Agrippina the Younger, did everything so that after the death of the emperor Claudius could be taken over by her beloved son Nero.

Nero ‘was at the age of seventeen, when Claudius was announced publicly. Between six and seven o’clock he went to the bodyguard, because he was so gloomy all day that only this moment seemed most appropriate for him to take power. He was greeted as an emperor before the Palatinate degrees , taken in a litter to the camp (praetorians)38. Then Nero spoke to the soldiers. After the speech he was transferred to the curia, where he was showered with lots of honors. Of all, “he did not accept only one title: father of the homeland , because of the young age of”39. The new princeps, proclaimed by the praetorians and approved by the senate, initially ruled in harmony with him having commissioned the reign of the praetorian prefect, Burrus and his tutor Lucius Anneusz Seneca, an eminent philosopher40.

Nero began his reign by worshiping his deceased father Claudius. “He gave him a great funeral. He gave a laudatory speech and made him a gods”41. He also officially gave solemn signs of worship to his deceased father, G. Domitius Ahenobarbus.

In the first few or several months of her son’s reign, Agrippina played the role of a true ruler of42. Nero “gave his mother the management of all private and public affairs”43, he did not interfere in government. Agrippina the Younger, she had to help Burrus, and the freedman Pallas as the minister of finance. A symbol of her position in the state were some series of coins issued in the early reign of Nero. His head was on one side, Agrippina the Younger – mother on the other. There were also ones on which both heads were placed on the same side, as if they were equal rulers. The inscriptions entitled her Agrippina Augusta mater Augusti – Agrippin’s mother Augustus. “On the first day of his reign, he gave the tribune on watch the slogan:” The best mother. “He often rode with his mother around Rome in her litter”44. All this indicated that at the beginning of his reign, Nero was treating his mother with the greatest respect.

Agrippina the Younger, despite the fact that Nero called her “the best mother”, that she took part in the official audiences of her son, participated in the deliberations of the Senate, which took place in the palace, she did not intend to resign from the power that she had during the reign of her husband Emperor Claudius. Already at the beginning of the reign of Nero, she contributed to the death of Asian proconsul, Junius Sylan. This was due to the fact that Agrippina the Younger “was afraid of him in the avenger, especially since among the commune there were frequent voices that above Nero, who barely came out of the boyish age and had the dominion through the crime, should be postponed a husband of stable years, unblemished, noble-born and – what was considered then – a descendant of Caesars; after all, Sylanus was the great-great-grandson of the divine Augustus. This was the reason for his murder. The tool was used by Publius Celer, Roman knight, and freedman Heliusz, both administrators of imperial goods in Asia. They handed the proconsul to the poison feast, too openly not to notice after them”45. Agrippina the Younger also quickly removed Narcissus, the freedman of Emperor Claudius, who “was put to death by a hard prison and ultimate misery”46. These were the first misdeeds of Agrippina the Younger in the early reign of her son Nero.

According to Tacitus, further murders would occur “if Afranius Burrus and Annaeus Seneca were not opposed to them. Those, as the leaders of the young ruler and – which in common with the authorities very rarely occur – agree, different means have equal influence: Burrus through his zeal for military matters and the severity of manners, Seneca, by his teaching of pronunciation and noble kindness”47.

The guardians of young Nero “together had to fight Agrippina’s wildness, which, burning with all passions of unhealthy self-rule, had Pallas on its side”48. Burrus and Seneca organized their own political party based primarily on “new people” from the Romanized provinces: the homeland of Burrus Gaul Narbonensis (southern part of today’s France) and Spain, where Annaeus Seneca49 came from. They, terrified by the ruthlessness of Agrippina the Younger, began to support the attempts of Nero, who began to strive for independence.

From the very first moment of exercising his reign, Nero wanted to consolidate a good opinion about his character, “he announced that he was going to rule in the spirit of August’s precepts. (…) The tax burden was too severe or reduced. (…) For the most outstanding, but he ruined senators with annual allowances, for some up to five hundred thousand. He gave free grain to the Praetorian cohorts every month. (…) He allowed the people”50” to his field manoeuvres.

He also kept his word and, at the senate’s discretion, many ordinances were issued so that nobody would be bribed by payment or gifts to defend the court case, that appointed quaestors would not be forced to issue gladiator games. Although Agrippina opposed the latter resolution, claiming that the decision of Claudius was overturned by her, senators displaced her, for which she was called to the palace, so that Agrippina could participate in meetings, behind the door behind and only separated by a curtain; she did take her view but did not prevent her from listening.

It is hard to believe that these orders came out of the order of the one that a few years later, crashed after the worst deeds, unconsciously shone with gold and mocked all rule of law.

It all came later, however. For now, Nero had the best intentions, listened to the admonitions and advice of his master Seneca and was passionate about poetry, music, sculpture and painting51.

However, this did not last long, because Nero increasingly strove for independence and total power in the state. He began to rebel against the excessive power and influence of his mother – Agrippina the Younger. His aim was to transform the Roman state into an absolute monarchy52. Gradually, the conflict between mother and son increased. He took on a sharp character in connection with a seemingly small matter. Nero, married before taking power with Octavia, the daughter of Claudius, did not have any feelings for her but fell in love with a freedman named Akte53. Nero’s actions were supported by his guardians, Afranius Burrus and Anneusz Seneca, because this pulled the emperor away from the government. “Acte lived a truly royal equipment: inscriptions mention her slaves and freedmen, among them servants, messengers, bakers, eunuchs, Greek singer. They also indicate that she owned villas in Puteoli and Velitrae as well as a brickyard in Sardinia54 Then Agrippina the Younger reacted with fury, shouting in public that “the freedman is her rival, a daughter-in-law, using other words of this kind.” She did not wait for her son to crumble or feel satiated; and the more insulting she reproached him, the more she aroused his passion until he, enslaved by the power of love, lost his obedience to his mother and entrusted himself to Seneca. (…) At that time, Agrippina, after changing her tactics, tried to flatter the young man, she rather offered him a corner of her own bedroom to hide the preferences that his young age and highest dignity demanded. She even admitted to his untimely severity towards him and gave him the resources of her own treasure, which was not much less than the imperial one – like too hard in taming her son recently, so now again humble”55. All these efforts of Agrippina The younger one, however, was not deceived by her son Nero. In turn, they began to bother his closest friends who asked him to be on guard before his mother, a dangerous and fake woman. During this time Nero was looking at the costumes that the emperors’ spouses and mothers used to wear , “of them he chose one robe and jewels and sent it to his mother, without thinking about savings, since he gave her on his own motives what was most important and desired by other women”56. Nero’s idea he angered Agrippina the Younger, who cried “that her dress was not enriched, but her right to the rest was forbidden, and that her son shared with her what she has”57 entirely from her. With this answer, she ultimately alienated her son, Nero, who” embittered with people who were supported by the pride of this woman, removes Pallas from the office supervised by Claudius how the ruler of the state affairs handled”58. In this way, Pallas, the actual minister of finance of the empire, the main ally of Agrippina the Younger, was deprived of his post.

“Since then, Agrippina has sharply shifted to terror and threats, and did not spare even the emperor’s ears, ensuring that the Briton, a true branch, had grown up, to take over his father from the rule that the intruder and the adolescent with hurt his mother”59. With this she issued Agrippina the Younger verdict on herself and the Britannia.

Nero, worried about the threats of his mother, and that the day was approaching when the Briton was fourteen years old, decided to poison the Briton first and then his mother. “He poisoned the Brit, both out of jealousy for the voice that Briton sounded nicer, and out of fear that he would ever overtake him in favor of the people thanks to the good memory his father left behind”60. During the feast, as Tacitus tells us, Nero decided to poison the Brit. Because the food and drink were first costed by a servant, a trick was invented not to reveal their criminal plans. “After tasting, the Britannian was given a harmless yet very hot drink; then, when the drop drifted away, the poison was poured along with the cold water, which spread so quickly across all its members that at the same time his voice and breath froze. A confusion arose among those sitting around , unaware they fled; but those who had deeper understanding remained as chained to the place and looked at Nero”61.

I, too, think, like many eminent historians of ancient Rome, that it was Nero who killed his brother Briton. I think that many factors influenced his decision. These included, among others: a momentous voice, the memory of Briton, which Nero envied him, as well as his mother – Agrippina the Younger, who blackmailed her son that with the help of Briton would deprive him of the throne. The Briton was the legitimate heir to the throne – he was the first-born son of Emperor Claudius.

The Britannian funeral took place, according to sources, in the Field of Mars, in the rain, without any ceremonies.

To drown out remorse, Nero “enriched his best friends with donations”62. However, his mother’s anger was not mitigated by any generosity, “she embraced Octavia, often had secret conversations with her friends, apart from innate greed, she drew money as if for an allowance, politely took the stands and centurions, respected the names and merits of the remaining nobility, as if seeking a leader and party”63. When her son Nero found out, “he first dismissed the posts of praetorians and German mercenaries holding the guard of honor in front of his mother’s apartments”64. “And that the multitude of those who greet her should not visit her, he disconnects his apartment and moves his mother to the one that once belonged to Antonia; and whenever he went there he was surrounded by a group of centurions and after a short kiss he left”65. Agrippine removed from the Palatinate was henceforth treated as a private individual. Her fall was welcomed with satisfaction, “for a woman who was pathologically ambitious and blamed for many crimes did not enjoy anyone’s sympathy”66.

As soon as the decline of Agrippina the Younger became visible, hostility towards her immediately spoke. Two women who had long been hostile to Agrippina decided to inform Nero that his mother had decided to marry Rubelisz Plaut, “who from the mother’s side equally with Nero from the divine Augustus”67. It was suspected that with his help he would want to destroy Nero – his son of the throne and again gain power in the state. The women who accused Agrippina the Younger were Julia Sylana, who Messalina deprived her husband of, Silius, and Agrippina deterred a young member of the senatorial state from her marriage. Agrippina the Younger wanted the husband not to overtake the property of Sylana, who after her childless death could have fallen to the emperor, and also her. The second woman was Domitia – uncle Nero, with whom Agrippina competed for influence. freedman of Domicja, favorite of Nero, actor Parys, reported an alleged conspiracy to Nero, who, terrified, wanted to lose both Plautus and his mother68. Seneca and Burrus dissuaded him from this intention and told the emperor that everyone, “let alone mother, should be given defense”69. Eventually, Burrus went to audition with Seneca. The freedmen were witnesses in this matter. Then Burrus, after making accusations and their sources, listened to what Agrippina the Younger had to say. She relied on maternal love and everything she did to ensure her son the imperial throne. He said that childless Sylana could not understand it, “because the parents do not change their children as the harlot of their gach”70. Then Agrippina the Younger had a conversation with her son – Nero, during which she managed to achieve the punishment of informers and rewards for her friends. “Supervision over the provisioning is entrusted to Fenius Rufus, the efforts for the games that Caesar organized, Arruncius Stella, Egypt to Tiberius Balbillus. Syria was assigned to Publius Antejusz, but later he was deceived by various tricks and finally arrested in the capital”71. So, to everyone’s amazement, not only did Agrippin leave the ambush, which was prepared for her destruction, but even improved her position72.

However, this was Agrippina Młodych’s last victory over her son and his accomplices.

After these events, the situation in Rome changed. This was because Nero was more and more afraid of his mother. In addition, after the victory of Agrippina the Younger over her son and his accomplices, the balance of power in Rome changed. A group of people appeared then, reluctant to Afraniusz Burrus and Anneusz Seneca, the current teachers of Nero. It was decided to remove them from power because, according to sources, they wanted to expel Emperor Nero from the throne – son of Agrippina the Younger. According to Tacit, Pallas and Burrus agreed to “appoint Cornelius Sulla because of the fame of his family and affinity with Claudius, whose son-in-law was married to Antonia. The perpetrator of this accusation was a certain Petus, famed by the division of confiscated treasury goods, and in this case an open liar. But not so much of Pallas’s innocence was comforting, but his unbearable pride (…) Burrus, although accused, was judging between the judges. Thus the prosecutor was sentenced to exile and the records were burned, from which forgotten fiscal debts were dragged out again”73. At the same time, Nero began to lead a promiscuous lifestyle. He roamed the city streets, harlot houses and pubs in a slave disguise, “having people as companions who robbed items for sale and inflicted wounds on those whom he encountered; they did not know their opponents to such an extent that he himself received blows and traces of them he wore74.

Away from his mother – Agrippina the Younger – Nero, he found a new friend. She was Sabina Poppea, whose father was Titus Olilius. “This woman had everything but an honest soul. After all, her mother, who surpassed beauty over the women of her era, inherited both fame and beauty; her property corresponded to the splendor of the family; her speech was endearing, and wit was not from things. (…) She never spared her good name and did not distinguish spouses from gachs, and without succumbing to either her own or someone else’s feelings, she moved her whims where she saw her benefit”75. According to sources, it was Poppea who contributed to Nero’s two monstrous crimes – murder and suicide. Because of these crimes, she wanted to become the official wife of the emperor, and she could only achieve this after removing Agrippina the Younger, and then Octavia. Sabina Poppea, insisting on marriage with Nero, led to the faster murder of his mother Agrippina the Younger. She blackmailed Nero, saying that “if Agrippina cannot bear another daughter-in-law but a hostile daughter-in-law, let her return it to her husband Othon; she will go anywhere, where she would learn by hearing about the insults inflicted on the emperor, rather than look at them here, implicated in his dangers. These and other similar words, thanks to the tears and the suit of the suitors, touched Nero’s heart, and no one counteracted them, because everyone wanted to weaken his mother’s influence, and nobody suspected that the son’s hatred was about to murder her”76. Nero’s decision to kill his mother was also accelerated by his fear that his mother could take his throne by preparing a coup d’état. These fears and suspicions were also shared by the emperor’s advisors, Burrus and Seneca.

Nero, since he deprived his mother of all badges of honor and authority, took the body guard and German unit, and expelled her from the Palatinate and from himself – he avoided meeting her in private. “In tormenting her he did not know the measure. He gave the thugs to disturb her trials during her stay in Rome; and when she took delays in seclusion, that they pursued her with insults and jokes, circling her on land or sea”77 .

“Finally, he came to the conclusion that wherever she was, it was a burden to him, and he decided to kill her; he was only thinking about whether he should use poison or iron, or any other violent measure”78. Initially, he chose the poison as Tacitus. However, he quickly stated, even before thinking about it, that “if asked at the emperor’s table, it could not be attributed to the accident, since the Briton was killed in a similar way; to tempt the servants of a woman, whose practice in crimes taught to be cautious about ambushes, seemed difficult ; in addition, she herself insured her body before taking antidotes. However, as one could hide the murder of iron, no one could find a way; at the same time Nero was afraid that the one whom he would see to commit such a great crime, he would not listen to his orders”79. Also A. Demandt states that “at the murder of his mother Nero had to give up the poison, because Agrippina was prepared for such an eventuality”80. Then, according to sources, Nero was liberated by Anicetus, who had been his educator before. Anicetus was the prefect of the fleet at Misenum. “He therefore instructs the emperor that it is possible to arrange the ship so that part of it at sea artificially disconnects and suddenly plunges Agrippina; nowhere are as many accidents as at sea; and since as a result of the shipwreck death will surprise her, who will be so unfair that guilt attributed winds and waves to crimes?”81. Emperor Nero liked this plan. In addition, the moment was conducive, “because it was at that time that he celebrated the festival of Quinquatras in Baja. There, he lured his mother, saying that it was necessary to endure the outbursts of anger of parents and calm their agitation, in order to cause a rumor of their reconciliation, and that Agrippina would receive her with the right women with naive faith in what makes him happy. And when she arrived, he came out immediately to meet her on the coast (because she came from Antium), shook her hand, shook her and led her to the Bauls. (…) Then she was invited to a feast to to hide the crime it was possible to use the night. It was quite known that a traitor was found and that Agrippina, aware of the assassination, but not sure if he would believe it, ordered her to carry to the Bajów in a litter. There, caressing dispelled her fear; Nero kindly he took it and put it above the table above him. Then talking more and more, already with youth confidentiality, it is again stately, as if y shared serious thoughts with her – he delays the feast for a long time, and finally walks away the departing feast, looking deeper into her eyes and snuggling closer to her breast, whether to complete the measures of hypocrisy, or at the last moment the sight of a mother who was about to die, even his wild heart chained”82. Then he sent his mother – Agrippina the Younger – to her villa on a special ship. Agrippina was accompanied by two people on the journey, “namely Crepereius Gallus, who was standing near the helm, and Acerronia. She, leaning on the legs of her lady resting on the sofa, just mentioned with joy about the repentance of her son and the restoration of maternal grace, when on a given mark the ceiling the cabins, heavily laden with lead, collapsed and crushed Kreperejusz, who gave up the ghost on the spot. Agrippina and Acerronia were protected by protruding sofas, which were strong enough by accident that they did not give way under load. There was also no loosening of the ship, because there was general confusion , and very many unaware creped those who were initiated. Later, the rowers decided to tilt the ship to one side and sink it”83. So, thanks to the help of Acerroni, who cried, “that she is Agrippina and that the mother of the emperor should be saved”84, Agrippina the Younger managed to get out of the assassination. Agrippina the Younger, “who was silent and as a result was not known (one wound was wounded on the shoulder), after getting out of the pool, and then thanks to the fishing boats encountered she was transported to Lake Lucryńskie – she had to be taken to her villa”85. But she guessed who had prepared the assassination attempt. Then she informed her son, Nero, that she had left the assassination and asked him not to come to her yet, because she needed peace. Nero, having received a message from his mother, became very nervous, fearing her revenge. He immediately convened a meeting with Burrus and Seneca. There was a dramatic conversation during which, after a long silence, Burrus and Seneca finally decided that it was impossible to go back: Agrippina must die, otherwise Nero86 will die. Burrus, however, when asked by Seneca if the soldiers of the Praetorian Guard could be used for the murder, said that “praetorians, obliged to the entire Caesar house and remembering Germanicus, would not dare to do any cruel act against his daughter; let Anicetus do what he promised”87. Seneca and Burrus’s consent accelerated Agrippina’s death. Anicetus and his soldiers directed the crime, and Envoy Agrippina the Younger was accused of assassinating the life of Emperor Nero, and then killed. Anicetus guarded the villa, then broke down the gate, kidnapped the slaves he encountered, and reached the bedroom of Agrippina the Younger – Nero’s mother. “There was only a handful of household members there, because the others fled, terrified of the soldiers’ intrusion. There was dim light and one servant in the bedroom, and Agrippina was more and more worried that no one came from the son, not even Agermus. (…) , she called after her: “Are you also leaving me?” Then he notices in the background Anicet in the company of the triearch Herculeius and the centurion of the Obarytus fleet. “If you came, he says, to visit, you can report that I am better off; if, in order to commit a crime, I don’t believe in my son’s guilt at all: he did not order the suicide! “. The murderers surround her bed and the first trierarch hit her with a baton on the head. When the centurion drew his sword to inflict a fatal blow, setting his life she exclaimed: “Settle here” – and on many occasions gave up the spirit”88.

In turn, Suetonius in his source claims that Nero “when he used the poison three times and saw that his mother was immune to its action, he set a special ceiling so that at night abandoned by means of a machine he fell on a sleeping girl. This intention was revealed by the initiates. Then he invented Nero a ship that can be dismantled so that as a result of its apparent shattering or collapse of the ceiling in the cabin, the mother would die”89. He later reconciled with his mother and invited her to Bajów to celebrate the Quinquatra together. He deliberately postponed the feast, and offered his returning mother from Bauli an artificial vessel. When “he learned that everything had gone awry and that his mother had come ashore, he stood helpless. Meanwhile, L. Agermus, her freedman, arrives with the good news that her mother had saved herself and left unscathed. Nero surreptitiously tosses him a dagger and he immediately orders to grab, shackle, as a substituted murderer, kill his mother by creating the appearance that she herself committed suicide, captured in criminal action. (…) Here, apparently, he himself came to see the body of the murdered, groped members, some rebuked, others he praised and, feeling thirsty, drank something”90.

A. Demandt, in turn, tells us that Agrippina the Younger was murdered by her son Nero, “because she did not stop raising him”91.

As you can see, all historians agree that Agrippina the Younger was killed by her son Nero. However, not everyone agrees with who persuaded Nero to murder his mother. Some say that Sabina Poppea was the main perpetrator, others find A. Burrus and A. Seneca guilty of the murder of Agrippina Jr.

In my opinion, Nero murdered his mother Agrippina the Younger at the insistence of Sabina Poppea. Sabina Poppea was at that time Nero’s mistress who was marrying him. Agrippina, reluctant to do so, was just an obstacle Poppea decided to destroy. Poppaia’s big help was also that in the immediate vicinity of Nero Agrippina the Younger did not enjoy popularity, and therefore did not prevent her scheming. In this way Nero led to the death of Agrippina the Younger – his mother.

“Whether Nero inspected the corpse of his mother and expressed approval of her figure is a statement which some affirm and some deny. She was cremated the same night, on a dinner-couch, and with the humblest rites; nor, so long as Nero reigned, was the earth piled over the grave or enclosed. Later, by the care of her servants, she received a modest tomb, hard by the road to Misenum and that villa of the dictator Caesar which looks from its dizzy height to the bay outspread beneath”92.

Agrippina the Younger believed many years earlier that she was over, but she disregarded it. “Namely, when she once asked the Chaldeans about Nero, they replied that he would reign and kill his mother, and she said: “Let him kill, let him reign”93.

Nero was not aware of her monstrosity until after the crime. He spent the whole night in fear, convinced that he would die at dawn, that everyone would turn away from him, as if he were a mother-killer.

It is worth asking a question here – did Nero have remorse after the murder of his mother? I think so, because losing Agrippina the Younger, Nero removed the only person who could help him. His behavior also testifies to this, as I wrote above. Besides, I think that Nero, being a twenty-two-year-old young man at the time, needed someone to direct him, help him and, if necessary, rebuke him. Who can give all this to a child if not a mother?

At the same time, I believe that Agrippina the Younger, being the mother of the emperor, did not have to die at such a young age. She was only 43 years old when she died. I think she was lost because she could not part with the authorities in a timely manner. At a time when the Roman Empire came under her son instead of her husband.

Agrippina the Younger – daughter of Germanicus and Agrippina the Elder – was an energetic and brave woman. She died with dignity because she pretended to the end that she did not believe in the crime her son Nero had committed. And so he characterized her in his work Tacitus, when she became the wife of Emperor Claudius: “From this moment it was a changed state, and all things moved at the fiat of a woman — but not a woman who, as Messalina, treated in wantonness the Roman Empire as a toy. It was a tight-drawn, almost masculine tyranny: in public, there was austerity and not infrequently arrogance; p327 at home, no trace of unchastity, unless it might contribute to power. A limitless passion for gold had the excuse of being designed to create a bulwark of despotism”94.

Agrippina the Younger – Nero’s mother – was lost because she could not part with power. It happened, in my opinion, when the empire came under the rule of her son Nero.

The death of Agrippina the Younger, as well as the death of her son Nero, ended in Rome by the Julian-Claudian dynasty.