Ammianus Marcellinus is the last great historian of the dying Roman world civitatis. His “History of Rome” (Res gestae) was written at a special moment when the Roman Empire was slowly entering a time of irreversible transformations, which consequently led to the shaping of a new face of Europe.

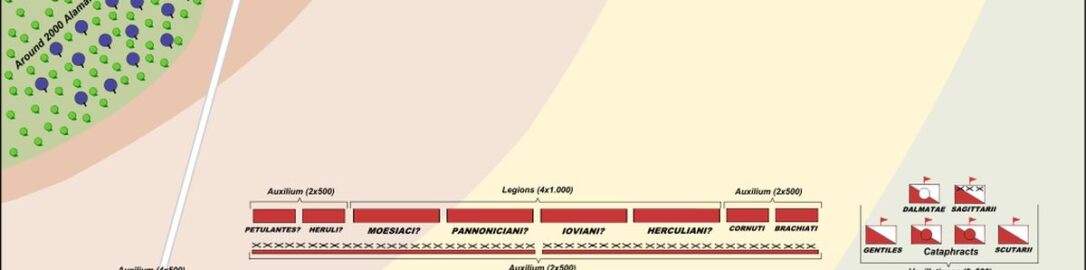

This work is an extremely rich panorama of Roman history from 96 CE to the Battle of Adrianople i.e. the year 378 CE Unfortunately, only 18 books from 353-378 CE have survived our times. The historian pays a lot of attention to the northern lands of the empire, among others Gaul, whose territory was regularly invaded by Germanic tribes. So it happened in 357 CE Caesar Julian set out against the Alamans. The decisive battle of this campaign took place at Argenturatum. The Germans were sure of their victory, the more that a fugitive from the auxiliary troops informed them that the Romans had only 13,000 soldiers. So they sent envoys to Caesar with a bold demand that he withdraw from the territories they had taken with their bravery and swords (Res Gestae 16,12,3). Julian did not negotiate and imprisoned the deputies.

The Battle of Argentoratum took place on a hot August day 357. On the German side, seven kings, ten princes, a long line of nobles, and 35,000 warriors fought on the German side (Acts 16:12, 26). Among the Germans, Chnodomar, the king of the Alamans dressed in a fiery plume, mounted on a mighty steed and leaning on an exceptionally long javelin, stood out in particular. Soon the trumpets sounded and the battle began. The barbarians prepared an ambush, hiding some of the warriors in the ditches, but the Roman commander Severus sensed the danger and cautiously advanced. Julian, watching everything from the hill, thought the Romans were afraid of a clash with the Germans. He rushed there immediately at the head of a bodyguard of 200 horsemen to encourage his own to fight. Suddenly, shouts of anger were heard in the ranks of the Alamannian infantry and confusion was noticed. The foot warriors demanded that the Germanic princes get off their horses and share all dangers with them. Chnodomar was the first to get off his horse.

With terrible screams and fury, waving their spears, thousands of Alamans rushed at the legionaries. The left-wing of the Roman army collapsed and the soldiers began to flee, but Julian immediately galloped there and urged the people to fight. The auxiliary units of the Kornutas (the name comes from the horn-shaped signs – cornua worn on the helmet and shield) and the Brakchiats (they wore cufflinks on their shoulders for a change, in Latin – braccae) and Roman allies – the Batavas also came to help. It was not the end of the struggle yet, because a group of Germanic warriors from the most eminent aristocratic families broke out to fight and broke the ranks of the Roman infantry with a powerful blow. It was the bloodiest for both sides, but the last spurt of the Alamans. The desperate assault failed, and the barbarians began to gradually retreat and then run away in the chaos. Many died in the treacherous current of the Rhine. The legionaries, on the other hand, set out in pursuit with such passion that the officers could hardly stop them.

According to Amman, the Romans died 243, including 4 senior officers. On the other hand, the losses among the Alamans were enormous; 6,000 were reportedly killed. Many were captured. The most eminent prisoner was Chnodomar himself, who was transported to Rome. He was kept under guard on Celius Hill. He died there after years of captivity.

And so ended one of the many armed campaigns against the Germanic tribes, which in the 4th century CE they did more and more boldly in the lands of the Empire.