Chapters

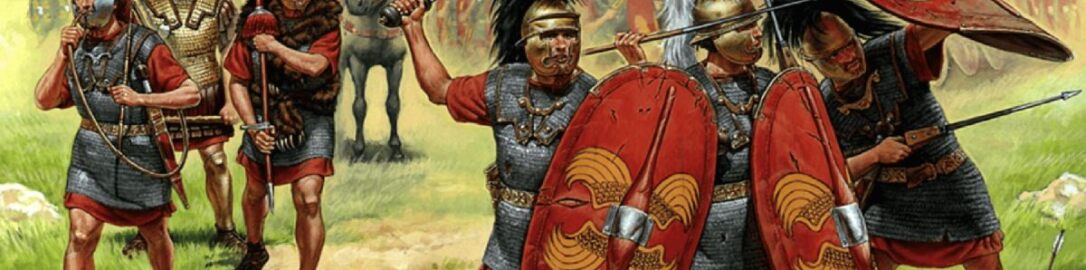

The wars fought by the Romans in the late Republic era made many legions, and even individual soldiers, almost as famous as their leaders. At that time, the Roman army was practically a professional army.

For Roman citizens who dreamed of social advancement or those who could not find another way of life, the warrior became the main source of income. The duty to serve in the army has passed since the consuls went to wars and were forced to enlist conscripts into the newly formed legions. The Roman Empire, which was constantly expanding its territory, was obliged to maintain it by placing garrisons, which translated into the constant recruitment of thousands of fresh legionaries. In addition, Roman legions evolved into well-established formations with permanently assigned numbers and names. This process was initiated by Mark Antony and Octavian, who, while retaining the veterans of Julius Caesar’s legions, reformed them. Final changes to the process were made by Octavian when he recreated his army after the Battle of Actium.

However, this text is intended to present the Caesar centurions, whom he himself mentions, their attitudes and behaviour during numerous wars waged by one of the greatest leaders in Roman history.

The Gallic Revolt

In winter, at the turn of 54 and 53 BCE, due to poor harvest, Julius Caesar was forced to disperse his legions throughout Gaul. The distance that separated the legions exposed them to numerous attacks because some legions were almost 160 kilometres apart.

The Eburon chief – Ambiorix – outsmarted the legate Titurius Sabinus and lured the 14th Legion under his command, and five other cohorts from the winter camp in northeastern Gaul then surrounded and defeated them. The few legionaries managed to break through back to the fort, but those who reached the fort were forced to close the gates and fight until dark. Plunged in despair, they took their own lives before the next storm. This defeat of the Romans provoked the Nervii tribe to attack another winter fort, but the legion commander Quintus Tullius Cicero (younger brother of the famous orator) did not take the bait and did not leave the safe fort. The Nervii, therefore, besieged the Roman camp in their own way, but the legionaries, and especially the centurions, repelled the attacks. During this siege, the centurions Lucius Vorenus and Titus Pullo, known to everyone from the TV series “Rome”, jumped off the embankments to see which of them would lay down the more advancing enemies.

In that legion there were two very brave men, centurions, who were now approaching the first ranks, T. Pulfio, and L. Varenus. These used to have continual disputes between them which of them should be preferred, and every year used to contend for promotion with the utmost animosity. When the fight was going on most vigorously before the fortifications, Pulfio, one of them, says, “Why do you hesitate, Varenus? or what [better] opportunity of signalizing your valor do you seek? This very day shall decide our disputes.” When he had uttered these words, he proceeds beyond the fortifications, and rushes on that part of the enemy which appeared the thickest. Nor does Varenus remain within the rampart, but respecting the high opinion of all, follows close after. Then, when an inconsiderable space intervened, Pulfio throws his javelin at the enemy, and pierces one of the multitude who was running up, and while the latter was wounded and slain, the enemy cover him with their shields, and all throw their weapons at the other and afford him no opportunity of retreating. The shield of Pulfio is pierced and a javelin is fastened in his belt. This circumstance turns aside his scabbard and obstructs his right hand when attempting to draw his sword: the enemy crowd around him when [thus] embarrassed. His rival runs up to him and succors him in this emergency. Immediately the whole host turn from Pulfio to him, supposing the other to be pierced through by the javelin. Varenus rushes on briskly with his sword and carries on the combat hand to hand, and having slain one man, for a short time drove back the rest: while he urges on too eagerly, slipping into a hollow, he fell. To him, in his turn, when surrounded, Pulfio brings relief; and both having slain a great number, retreat into the fortifications amid the highest applause. Fortune so dealt with both in this rivalry and conflict, that the one competitor was a succor and a safeguard to the other, nor could it be determined which of the two appeared worthy of being preferred to the other.

– Gaius Julius Caesar, Gallic Wars, 5.44

The legion, whose number Caesar did not give, remained until the Chief’s relief. The attackers were repulsed and vanquished. Then Caesar took his revenge on the Eburones, destroying their lands in 53 and again in 51 BCE. He never captured Ambiorix, but despite winning the first round, he did not expect that the discontent of the Gauls would lead to their reunification under the charismatic Vercingetorix.

Siege of Gergovia

Gergovia – the capital of the Arverni – was situated on a plateau between modern Lyon and Clermont-Ferrand. The foot and the top were over three hundred meters. Vercingetorix chose a plan that was designed to tire the legionaries up the steep slope and then kill them in an assault.

Unfortunately for Caesar, the hill was too large to be surrounded entirely by siege lines, so the Romans founded it on the southeast side, and Caesar decided to storm a less steep slope from the south and conquer the plateau, meter by meter, piece by piece. At the behest of their commander, the legionaries dug a double ditch surrounded by embankments, leading from the main camp to the smaller camp, located on a hill, centrally opposite the site of the attack. The height of the ramparts meant that the defenders could not see the attacks of the attackers, thanks to which the Roman troops were transferred to the camp on the hill. Still loyal to Caesar, the Edu Cavalry launched a mock attack and distracted the defending Gauls, causing the Romans to launch their actual attack. The target of this attack was not Gergovia itself, but the camp outside the city established by Gallic troops. Following the blow, convinced that they would be victorious as usual, they began to storm the walls of the Arvernian capital. There was a catastrophe. Those legionaries who managed to climb the walls were surrounded and cut into the trunk, the rest panicked. The Edu cavalry appeared, and Caesar’s soldiers mistook them for attacking rebels and rushed to flee down the slope. The Gauls followed the Romans, killing nearly seven hundred of them. The greatest loss for the legions was the death of 46 centurions, who remained in their positions to the end, shielding the panic retreat of the legionaries. Julius Caesar in his work “On the Gallic War” describes the dramatic death of one of the centurions of the 8th Legion.

At the same time Lucius Fabius the centurion, and those who had scaled the wall with him, being surrounded and slain, were cast from the wall. Marcus Petreius, a centurion of the same legion, after attempting to hew down the gates, was overpowered by numbers, and, despairing of his safety, having already received many wounds, said to the soldiers of his own company who followed him: “Since I can not save you as well as myself, I shall at least provide for your safety, since I, allured by the love of glory, led you into this danger, do you save yourselves when an opportunity is given.” At the same time he rushed into the midst of the enemy, and slaying two of them, drove back the rest a little from the gate. When his men attempted to aid him, “In vain,” he says, “you endeavor to procure me safety, since blood and strength are now failing me, therefore leave this, while you have the opportunity, and retreat to the legion.” Thus he fell fighting a few moments after, and saved his men by his own death.

– Julius Caesar, Gallic Wars, 7.50

The extraordinary bravery of the centurions was paid for with their own blood, because in such a pogrom they set an example to the rest of the legionaries of their courage and stubbornness, but also their desire to get the greatest possible loot.

Battle of Dyrrachium

In early 48 BCE, during the ongoing civil war between Caesar’s supporters and the so-called Pompeians, Caesar managed to accumulate enough transport ships to cross the Adriatic Sea for a large part of the army. Ultimately, there were not enough ships to carry all the legions in one go, so some of them had to return for the rest waiting in Italy. At the same time, Mark Antony was temporarily blocked in Brundyzjum (today Brindisi), and Pompey marched from Greece to the territory of today’s Albania to stop the march of Caesar’s army. However, he did not want to face the veterans of his opponent and chose his tactic to wait until Caesar’s legionaries ran out of food supplies and the morale of the army collapsed. Pompey’s plans fell into ruin and he had to go on the defensive after the news that Mark Antony had managed to slip through his blockade and joined Julius Caesar’s troops. Pompey’s army withdrew to strong positions on the coastal hills of Dyrrachium (today Durres, Albania). Despite the much smaller number of legionaries, Caesar ordered to build defensive fortifications, to which Pompey replied, building them exactly opposite to the Caesarian positions. Caesar’s troops ran out of food, and his lines stretched 27 kilometres, making them extremely difficult to man. Pompey exerted great pressure and constantly carried out attacks on enemy positions. On the other side, despite the lack of food, the legionaries were firm, but it all depended precisely on the fortitude of the centurions. One of the forts was especially fiercely attacked by the Pompeians.

[…] there was not a single one of the men who was not wounded and four centurions out of one cohort lost their eyes. Wishing to produce a proof of their labour and peril, they counted out to Caesar about thirty thousand arrows which had been discharged at the redoubt, and when the shield of the centurion Scaeva was brought to him one hundred and twenty holes were found in it. For his services to himself and to the republic Caesar, having presented him with two hundred thousand sesterces and eulogized him, announced that he transferred him from the eighth cohort to the post of first centurion of the first cohort, for it was certain that the redoubt had been to a great extent preserved by his aid, and he afterwards presented the cohort in amplest measure with double pay, grain, clothing, bounties, and military gifts.

– Julius Caesar, Civil War, 3.53

Centurion Marcus Kasjus Scewa independently defended the entrance to the camp, while many soldiers from the unnamed legion escaped in the face of the onslaught of Pompey’s legionaries. At first, he fought in the gate himself, but with time he withdrew to the rampart. His face was covered with blood because one of the arrows had stung his eye. Roman sources report that the helmet of centurion Marcus Cassius Scseva was shattered in combat and at one point he used a stone to smash the skull of a Pompeian legionary. The spear points cut all his limbs. Nevertheless, he steadfastly attacked his enemies, slashing and stabbing them until his sword was dull. The opponents backed away and waited for him to bleed out. As he fell to his knees, he called in a low voice to the enemy who surrounded him to lift him off the ground. Two soldiers stepped forward for the task, but the centurion unexpectedly stabbed one in the throat and severed the arm of the other, paralyzed by fear. The fleeing legionaries paused to watch their centurion’s fierce defence. Some of them rushed to his aid, and the Pompeians did not attack them but stood stunned with terror, allowing the wounded centurion to be lifted from the battlefield. After which the gate of the fort was closed. He probably became one of Caesar’s favourites, and Cicero described him as a very dangerous man. After Caesar’s death, he served his successor – Octavian Augustus, during the siege of Perusia in 41 BCE.

Another example of the steadfastness and devotion of the centurions to Julius Caesar is the work of an unknown author of the African War. The anonymous author proudly mentions the martyrdom of the 14th legion loyal until the death of the centurion, whose ship was intercepted by Pompey’s ships in the years 47-46 BCE go to their site. The rebellious centurion answered him:

For your great kindness, Scipio — I refrain from calling you commander-in‑chief — I thank you, inasmuch as you promise me, by rights a prisoner of war, my life and safety; and maybe I should now avail myself of that kind offer, but for the utterly iniquitous condition attached to it. Am I to range myself in armed opposition against Caesar, my commander-in‑chief, under whom I have held my command, and against his army, to sustain the victorious reputation whereof I have been fighting for upwards of thirty‑six years? No, I am not likely to do that, and I strongly advise you to give up the attempt. For you now have the chance of appreciating — if you have not previously found it out sufficiently by experience — whose troops they are you are fighting. Choose from your men one cohort, the one you regard as your most reliable, and array it here over against me: I for my part will take no more than ten men from my comrades whom you now hold in your power. Then from our prowess you shall realise what you ought to expect from your own forces.

– Anonymous, African War, 45

Marcus Cassius Sewa and the aforementioned centurions are the personifications of the qualities thanks to which the Romans won wars: merciless, brutal, rebellious and never forgiving regardless of the situation. Caesar relied on such bravado and rewarded her handsomely. This is evidenced, for example, by Scewa’s advancement from the eighth cohort to the first (centurions of the first cohort, higher were in rank than those in cohorts from II to X). Caesar, Marcus Antony and Octavian saw in the centurions the factor that determines the fate of battles. They were an impeccable example of bravery and fortitude that animated the actions of the legionaries.