Chapters

When a favourite horse of Emperor Caligula, gracefully named Incitatus (Swift), was appointed senator, many pointed out his Spanish origins and the fact that his original name was Porcellus (Piglet). The benevolent lawmakers were blinded by the sight of Piglet’s golden manger, a harness studded with precious stones, and 18 servants serving the brave senator.

The emperor cared little for comments about the bumpy political path he had taken for his favourite mount. Historians argue how much influence Piglet had on the politics of the Roman Empire, but they know that it was only a part of the adoration with which the Romans treated their horses. Here is their story.

For a historian, the Roman state is what the Himalayas are for a climber. The history of the over 1,200-year-old empire continues to fascinate next generations of researchers. The Roman hippie was a specific synthesis of all cultures that were part of the multinational colossus. The Romans, whose most outstanding trait was the rapid ability to absorb the best of everything, both from enemies and conquered peoples, took advantage of it to the full. So these were influences, among others: Gallic, Numidian, Illyrian, Sarmatian, Parthian, Sassanid, Greek, Germanic, Palmerian and Hunnic techniques– of course, every technique of the above-mentioned, were adopted and adapted to Roman needs. To illustrate the multitude of styles and techniques of riding, suffice it to say that historians to this day are often unable to identify the role and manner of riding many horse units listed in official military lists. This is especially true of the late Roman ride. In this section, we will try to persistently follow the traces of Roman mounts, describe their role in combat, transport and in the sports arena. We leave the evaluation of our investigation to the Reader. Therefore, we wish you a pleasant reading and invite you to a trip to the country of Caesar and Horace, full of splendor, intrigue and wealth.

The Romans’ worship of horses is perfectly illustrated by the story of Emperor Caligula named Incitatus(initially his name was Porcellus, which means Piglet, but Caligula found the name unworthy and changed it to Incitatus – Chyży). The steed from Spain had a marble box, an ivory manger, purple rugs, pearl necklaces, around its neck, and it ate oats with flakes of gold. Moreover, Incitatus had the dignity of a senator (the mad emperor intended to promote him to the rank of consul, but did not manage to do so. At the time of his death, Incitatus lacked the 3 years required by Roman law to take the position. Caligula’s successor, Emperor Claudius, removed the horse from the senatorial state on the grounds of lack of property and permanent income). Incitatus was the owner of a crowd of slaves, he was surrounded by his own personal guards, he also had his own manor. On his behalf, guests were invited to grand orgies organized under his patronage. Emperor Caligula himself invited Incitatus to his table many times, personally offering him barley and wine from the golden goblet. As it happens with horses, he is a multidimensional and highly unknown figure. It is difficult to define exactly how much influence Senator Incitatus had on the shape of the policy of the Roman Empire. Historians are not entirely in agreement on this point…

The famous Roman poet Virgil describes the ideal horse as follows: “High neck”, “short belly”, “elongated head”, “full back, chest the heat of the muscles does not hide “,” you will recognize a noble foal by the proud expression and nervous legs “,” the spine doubled in the cross “,” the horned hoof is ringing and solid “. Pliny Secundus adds that the “chestnut and the spotted” horses were valued, while the “dun” horses were less valuable. When buying a horse, attention was paid mainly to the legs and hoof. Often, following the example of eastern peoples, the buyer demanded that the silhouette of the entire horse should be covered, revealing only the legs. This was to objectively assess the value of the steed so that the buyer would not be fooled by its beauty. A measure of the quality of the hoof, as in Greece, was the sound the hoof makes when it hits the pavement (numerosum sonitum). Many Romans attributed individual characteristics to certain horse colours, e.g. mousy – best for hunting, greyish for racing, grey and dirty chestnut for breeding.

The Romans cleaned their horses with coarse palm leather gloves, horsehair brushes, sponges, wooden knives to scrape sweat and wooden scrapers. Horses were covered with rugs at night in the stable. The mane and tail were washed with aromatic oils. They were cut with knives in a brush or trimmed on the left side so that the hair fell only to the right. Very often the horses were not cut off the mane at all, only the weaker ends were removed. Lips were also softened with oil and water. The hair in their ears was also cut. After each work, the horses were washed with exceptional care for the legs. It was thought good to stroke and pat young horses while they eat in order to establish a bond between them and man.

The main ingredients of the food were straw and barley. One of the historians of that period, Pliny, writes that the daily food ration was 15 Roman pounds. Sometimes hay and wheat were served. In the spring, it was recommended to use cereal forage, but it was advised, however, to bleed the blood of the horses during this diet. In summer, the horses were fed pure barley and released onto fresh grass for the whole day. During the winter, the horses were fed with peas to the evening meal for better digestion. Grain oats were not used. Chaff and chaff were also added to the horses. Horses that did hard work, and at the same time stayed in the stable for a long time, were fed with bran and boiled barley. They were also given parsley and celery to cleanse the blood. The custom of feeding the horse alfalfa was transferred from Persia. It was thought that there were two types of grass growing in Crete, one enlarging the spleen and the other reducing its size (the large spleen was perceived as an inconvenience because it slowed the horse’s pace). Salt, saltpetre, vinegar, pepper and honey stimulated the sex drive of the mares.

The Roman stable was a practical and cleverly thought-out building. It was made of brick walls with grooves. There was a 1 inch wide, 1 foot long rectangular opening above each stand, through which a line was led from the halter to a small weight attached to the end of the line between the groove and the wall of the barn. Above, there were small square vents. Straw was used as litter. The floor was constructed from 1 pound paving stones or oak wood. Tar, donkey fertilizer, olive oil, vinegar, ivy seeds and garlic were added to the substrate. The stable was very clean and the bedding changed every day. The horses were separated by beams. There were hay and straw ladders in the stables.

A lot of attention was paid to breeding horses with the best traits and pedigrees. When buying potential stallions and mares, the genealogical line of horses, confirmed by documents, was always the basis. The stallions that were to be admitted to the mares were carefully selected and selected so that fertilization did not occur by accident. When selecting the appropriate genealogical lines, the following principles were followed: corpora praecipue matrum legant – a good choice of mothers. It was believed that the fetus would be more influenced by the mare’s blood. Their age when they could have offspring was determined between 2 and 10 years of age. It was advisable that the mares were lean and very well-run before fertilization.

The stallions, apart from the appropriate origin, had to have a documented sports history. Their age, when the semen is of the best quality, was determined between the ages of 3 and 20 (the older ones were thought to produce offspring with weak legs). The ideal was an active sports stallion at the age of 20. It was advisable that the father of the future offspring was well-fed and fat. The stallion was admitted to the mares right after a slight effort. This was to prepare him for the best possible jump on the mare. Even the most distinguished horses without proper origin (prolemque parentum) as breeders showed little value. The place and the setting for the intercourse were carefully selected. Music was played during horses’ copulation. Around them were placed statues and paintings of beautiful mares and stallions, which were supposed to stimulate the horses’ imagination and increase their potency.

The Romans had a very highly developed equestrian technique. The way of riding they created can be described as: extremely shortened in place, shifting, devoid of stretched gaits, very much tucked up, even danceable, pragmatic and comfortable. According to M. Czapski, they distinguished 5 paces:

- Ambularia – amble, shuffle.

- Trot – Tormentor crutiator, succussator – (“tormentor” of the cross, “tosser”) – many believe that the trot was rarely used due to the discomfort of this gait.

- Tripudium – it was a parade move, reminiscent of today’s piaf or passage.

- Cantherius – slow gallop.

- Cursus equicitatus – gallop.

- Walk.

They divided certain steeds into 17 specializations: avertarius – horse to the road; solutarius – manege; gradarius – combat; cursor – racing; equus cantherius – walking; venator – hunting; saginarius – pack; ambolatorius – monohydrate; clapper, veredus – postal; curulis – coachman; vectarius – truck; equipares – teacher horse, trainer horse; triumphales – horse of triumphal chariots; equus singularis – a rider’s horse accompanying a cart at the Games; jugles – drawbar horses; funales – drag (sinister left, dexter right); asinus – donkey. There were also several varieties of ointments: albus – gray; maculatus – piebald; bicolour – taranth; scutalatus – bluish-grey; badius – bay; badius niger – scarps; gilbus – fawn; rufus – chestnut; fulvus – dills; niger – punishments; cinerius – grayish; ferugineus – roan.

Horses were named after gods, rivers, heroes, virtues, or winds. The profession of horse riding teacher (equisones) was very popular in Rome. For the ride, small, slightly bent spurs (calcar) and a small pillow (ephppii) were used to stick to the back with a breastplate and podogony and an elastic belt running under the abdomen. Young foals were accustomed to walking on a line and communing with humans at the age of 1.5 years. During this period, efforts were made to familiarize them with noise and the system of punishments and rewards. For this, large and blunt bits as thick as a male finger was used, placed where the horse has no teeth. It was extremely important for the bit to be balanced and to exert the same tension on both sides of the mouth. The individuals who had been bridged for the first time were left in the box for a long time to get used to this novelty. Whips of different lengths were mainly used for hand-held work. Music was used during the training to soothe the horse and ennoble it. The actual training started when the horse started 4 years of age. The horse was mounted in 2 possible ways:

- From the stand – it was a kind of stairs on which the rider would climb after putting his horse to the side. Pragmatic Romans used this type of boarding most often. This is evidenced by the fact that in cities and along roadsides such aids were set up for the greater convenience of travellers.

- Leaping from the runway – a method practised especially since the 3rd century CE in the army. It was a soldier’s duty to be able to jump onto a horse immediately in full gear.

The basic exercises were:

- Driving straight.

- A square-shaped volt ride with truncated corners.

- Returns on the rump.

- Gallop from volts to straight lines.

- Gallop from place / canter to halt.

- Gallop to stop.

- Gallop up / down.

- Jumping, jumping from horse to horse while running.

- Hopping on a horse fully armed.

- Throwing javelin at all gaits.

- Creating defensive formations (most often side pieces) using the shield.

- Thereafter, archery in all gaits.

The following were considered erroneous:

- Riding in stretched gaits, not collected from the so-called “stretched legs” (sit que laboranti similis).

- No permeability, horse reluctant to bite (cervix repugnat habenis).

- A horse’s neck stretched while riding (it was supposed to indicate a bad fit and the horse’s physical weakness).

- Trot riding.

Bits were not fitted to sensitive horses. Stirrups were not used. Horses were not shoed, but had wooden or fabric hoof protectors. The surface of the manege was very well taken care of by sprinkling it with fine sand. During the exercises, voices and pecks were used. The mount of the rider was similar to the Greek one with the difference that the weight of balance and giving orders to the horse was transferred from the thighs to the spurs and calf. It is also worth adding that compared to the prices of horses in ancient Greece and the Roman Empire, there was a significant increase (in Greece for a horse from 3 to 20 minutes, in Rome, legends say 100,000 sesterces for a sports horse).

In the Roman Empire, the art of driving was very popular. The general mechanism of the carriage consisted of a saddle fixed in place to the drawbar cross member, forming a formal yoke. There were many types of carriages, e.g.:

- Cisum – for a short fast ride.

- Monacus – a one-horse car.

- Currus augustanus – senatorial car.

- Sordidum – economic.

- Gestatorium – cruise.

- Onerarium – to take away killed arenas.

- Quadriga – the most popular four-wheeled car in Rome.

- Triga – three horse.

- Rheda meritoria – traveler.

- Lectica mannalis – a travelling litter for women harnessed to two inocods.

Carriage races (certamina equestria) aroused great emotions. Quadrigas with fixed axles and wheels with spokes took part most often. They were held at the so-called Circus Maximus – a huge hippodrome, which during the reigns of Emperors Augustus and Nero could accommodate 260,000 spectators. The racers were divided according to 4 colours symbolizing the seasons: green (autumn), white (winter), blue (summer), red (spring).

Each colour had its own stable, fans, chiefs (domini factionum), party and high-ranking protectors (for example: Caligula liked to get drunk with the party of greens). Roman hippodromes were built on the model of the Greek ones. They were rectangular in shape. On its sides there were seats for spectators separated by ropes, a water ditch (euripus) and a grate (cancelli) from the arena. The places on balconies called Opidum were occupied by the poorest class of citizens. The judges occupied turrets built into the corners of the arena.

On the outer side walls, there were shops and corridors. The arena separated by a rampart (spina – 5 feet high and 10 wide) was 2,187 feet long and 960 feet wide. On Spina, statues and symbols of various deities were placed. Music played all the time during the competition. Auriga competitors waited for the run in 12 carriages located in one of the shorter walls. They lined up at the starting line at a sign given with a handkerchief (mappa) by the praetor. As the rope fell, people were racing (missus) for seven laps around the spin to the finish line (meteae). In terms of today’s length units, it was calculated that the racers travelled 8,400 meters on a 1,200-meter-long track.

The Roman horses racing in the quadrigas were known for their excellent training. This is evidenced by the case of the horses of Emperor Claudius whose coachman fell out of the quadriga at the start. Despite the lack of a driver, they ran 7 laps and won. After the race, they obediently positioned themselves at the finish line.

It was customary for racehorses to decorate the funeral processions of the emperors. Bronze monuments and pyramid-shaped posthumous mausoleums were erected for famous racehorses. Portraits of the most beautiful or famous horses were placed on coins and precious stones. It was also fashionable to deliver poems of praise in honour of horses, listing in detail their origins and achievements. Many emperors personally competed in quadriga races. One of the most controversial fans of the sport Emperor Commodus (from the movie “Gladiator”) appeared 735 times before audience as the driver.

The races were usually held on the occasion of a festive celebration. There were as many as 200 holidays in Roman tradition. There were over 100 races every day. Fatal accidents occurred very often among drivers. The drivers made great fortunes. One of the most famous was Aurelius Mollicius, who at the age of 20 had almost 150 victories. The surviving veterans boasted up to 3,000 victories. They were undeniable idols at the time. Their images decorated plates and cups. Poems were written about them and slogans were placed on the marble in their honour.

Civilian transport

Land transport in the Roman state, as well as throughout antiquity, was much less important than sea transport. This was due to the still not reformed girth-dewlap harness. Two horses or mules pulling carts in such a harness could pull no more than half a ton of material on the cart. 80,000 km of famous Roman roads, which, although accessible to everyone, were created mainly for the smooth movement of the army, did not help. On these roads, milestones were set every 1,000 steps, and every 15 meters, stands for boarding transport animals. The condition of the roads was supervised by the curule aediles and road curators. The paved roads were extremely wide and massive. Their surface, however, was a disaster for horses that were not yet shod (since April, a leather caftan on a hoof was gradually introduced).

The Romans had amazingly fast horse mail. At each route, there were special postal stations at certain distances, where horses were exchanged. Each station had to have no less than 40 horses. The distances by rushing postmen were measured with milestones along the road. The pace with which the urgent message was travelling was 80-135 km per day. The mail was intended only for state officials. Its main task was to ensure smooth and uninterrupted information communication between the province and the metropolis. The post also performed public, economic and, from time to time, military transport. Initially, messages were carried by cursores, originating from the slave state. Private messages were sent by their messengers.

The first major reform of the state mail was carried out by Octavian Augustus at the beginning of the 1st century CE. He introduced additional juvenes officials with vehicles along the military roads to ensure a faster flow of messages through the relay system. From then on, mansio post stations also served as stops for troops. It was their duty to keep horses, harnesses, donkeys and oxen always ready. In this phase of development, the stations were maintained at the expense of the local population. This changed with the decree of the Emperor of Nerva at the end of the 1st century CE. The Act, which was commemorated with the commemorative coin Vehiculatio Italiae Remissa, removed the burden from the population by laying it down to the state treasury. This ordinance was repeated several times under Emperor Hadrian at the beginning of the second century and was meticulously introduced throughout the territory of the Roman state. From that moment, the post office became an office with its fleet and employees.

The livestock fleet was to be replenished once a year and 1 of its resources was to come from the local population. This was to protect against any abuse. Only officials with the imperial traction guideline could travel by such post. This was adhered to extremely strictly. An example of the care the Romans showed in this matter is the letter of the famous writer and governor of Bithynia and Pontus – Pliny the Younger to Emperor Trajan. Pliny writes in that letter and explains his wife’s trip to her aunt by postal transport in a very effusive way. The order of the entire mail was supervised by the Praetorian Prefect, the commander of the emperor’s bodyguard. After the crisis in the 3rd century CE, the post office was handled by the vehicle prefects stationed at the provincial governor. The station managers were subordinated to them, and so were the station staff: farmhand, muleteers, horse-riding, wheelwrights, veterinarians, coachmen and drovers. Couriers played a very important role, as they were responsible for the supply of fodder. As their job required long raids around the area, they also acted as informers and spies. The peak of their importance fell on the reign of Constantine the Great, who made them a separate organization of imperial agents.

An equally important function was played by the peasants who were responsible for servicing travellers, i.e. providing them with: beds, mattresses, fuel and accommodating them. In the event of an imperial passage or a larger march of troops, additional horses had to be provided by the closest farms. These extra horses were called paraveredi. The very arrival of the emperor or his high-ranking envoys caused a hecatomb of fear and then total havoc with the station and its surroundings. It happened so because the basic allocation for such guests included: bread, wine, bacon, pigs, piglets, lambs, lambs, geese, pheasants, unleavened honey, cumin, pepper, cloves, cinnamon, dates, pistachios, almonds, salt, wax candles, vegetables measured in the number of carts filled with them and from several dozen to several hundred torches. A similar disaster was the marches of troops that forcibly confiscated horses, donkeys, oxen and herdsmen.

After the political and economic crisis that fell on the empire in the middle of the 3rd century, the post office is reorganized by Constantine the Great. During his reign, postal transport was intended for supplying the manor, and army marches and supplementing its rolling stock, as well as for officials. At that time, very high penalties were imposed for the embezzlement of buying and selling postage animals and state wagons. Requisition from the adjacent population of animals used for ploughing was completely forbidden. The administration of Constantine also introduced a ban on charging more than 100 Roman pounds on pack animals, and on carts, not more than 1,000 pounds (rounded up, it can be assumed that 1 Roman pound is 327.45 grams and was called libra). It was also forbidden to use long braided whips to drive the animals. On the other hand, small sticks were allowed. It is also assumed that the postal vehicles moved at a speed of 40-45 km per day. The most popular vehicles of the central and late republic were the so-called rheda and angria.

Agricultural guides were very widespread among the pragmatic Romans. Horses were given a lot of attention. These animals are very interestingly described by Rutilius Taurus Aemilianus Palladius in the work “Opus agriculturae”:

- “Horse stables should face south. On the north side, they should have hoses closed in winter, opened in summer. They should stand higher than other buildings to protect animals’ hooves from moisture. soft, and standing firm. The yard of the stable should be facing south and exposed to the sun, in order to protect the horses from the summer heat, eaves of poles and branches should be built, covered with tiles, shingles, rushes or gorse”.

- “It doesn’t matter where the hay sheds are, as long as there is little airflow and dry ground. Far from the buildings due to the risk of fire.”

- “Donkey fertilizer is the best and is suitable for gardens”.

- “Horse’s hooves were used to ram the threshing floor just in front of the threshing floor.

- “Marcusing horses in January”.

- “Stallions for mares were admitted in March. Relatively, from the assessment of the stallion’s strength, he should cover a few or a dozen times, not more than 12-15 times. Thanks to this, he will not age for a long time. A perfect stallion should have a massive and strong body, adequate height for strength, long side, massive and round croup, broad chest, whole body filled with plexuses of muscles. Slim and strong legs with concave hooves beginning higher. The stallion should have a small and delicate head, short and expressive ears, skin almost close to the bones, big eyes, gaping snouts, low hanging mane and tail, and strongly and permanently rounded hooves Mating stallions should be chestnut, golden, whitish, reddish, brown, fawn, dusty gray with spots, white speckled, white, and black. choose light-coloured stallions with uniform coats Stallions should be kept separately so that they do not bite each other. my belly, of the same build as the stallion. The age of 2 was considered the best time to cover the mares. It was not recommended to fertilize mares after the age of 10, because she gave birth to sluggish and slow offspring. The mares, who did not want to let the stallion come to them, were smeared with grated moss. Mares of noble breeds should be mated every two years to provide them with clean and nutritious milk. Pregnant mares should not be forced to run, but fed until they are satisfied. They also had to have warm and spacious boxes. However, this only applies to horses of a noble breed. Non-noble horses can fertilize all year round. In winter, sunny and grassy pastures were set aside for horses, and cool and shaded areas in summer. Pastures could not have too soft ground for the hoof to retain its hardness. Foals should not be touched by hand until 2 years. They should be very protected from the cold. The horses were driven to the age of 2. Good features of foals are cheerfulness, speed, liveliness and massive, elongated bodies, full of visible muscles, equal and small testicles, and also features similar to covering stallions. The Romans were able to distinguish age on the basis of teeth (a horse at the age of 2,5 loses the upper middle teeth, in the fourth year of life it exchanges its canines (canines), before the sixth year its upper molars (molares) fall out, at the age of 6 it replenishes the teeth that it lost first, in the seventh year of life, all teeth are restored, after this time the age of the horse could not be recognized). In March, stallions unsuitable for breeding were castrated”.

Hippika Gymnasia

Until the end of the 2nd century, Roman military horseback riding was to the greatest extent modelled on the Gallic horsemen. However, this was not the only pattern. Virtually every corner of the empire was driven differently, and in the military these influences were mixed. The foundation for the Romans themselves, however, was the cavalry of Gauls and Germans. This changed in the middle of the 3rd century when the military patterns of the eastern cavalry began to take precedence. In the earliest period of Roman history (7th century BCE), only a citizen with the appropriate property status could become a soldier, which would allow him to buy equipment. Moreover, what is interesting, he did not receive any pay or rations. The soldier of the beginning of the monarchy had to be fully independent financially. Citizens were divided into 3 tribes, each of them consisting of 10 curiae. In the event of an external threat, each curia was to deploy a 100-person infantry unit, the so-called centuria. So, in total, the 3 tribus put up a total of 3,000 armies. In addition, each of them was obliged to put up a unit of 100 riders, which in total gave 300 riders of all tribes. The tribus commander was a military tribune. New reforms were introduced by King Servius Tullius (578-543 BCE), who divided the society into 5 classes according to the property census. And yes:

- Property Class I – citizens with a net worth of more than 100,000 aces. Their weapons were: a helmet, a round shield (clipeus), greaves, armour, a spear (hasta) and a sword. The strength was 80 centurions, 12 of which formed the cavalry composed of the richest inhabitants of Rome.

- Property Class II – citizens with a net worth between 75,000 and 100,000 aces. Their weapons were: a helmet, an oblong shield, greaves, a spear (hasta) and a sword. The strength was 20 centuriae.

- Property Class III – citizens with a net worth of 50,000 aces. Their weapons were: a helmet, an oblong shield, greaves, a spear (hasta) and a sword. The strength was 20 centuriae.

- Property Class IV – Citizens with a net worth of up to 25,000 aces. They were armed with a spear (hasta) and a javelin. The strength was 20 centuries. This class also exhibited two centurions of horn and trumpet players.

- Property Class V – Citizens with a net worth of up to 11,000 aces. Their weapons were: slingshots and throwing stones. The strength was 30 centuriae.

Citizens below the 11,000 aces threshold formed one centuria and were not admitted to military service. Thus, the Roman army in the 6th – 4th centuries BCE numbered 19,300 soldiers, 1,200 of whom were cavalry. During this period, the Romans fought like the Greeks, so using a phalanx. During the next conquests of Italy, the strength of Roman troops was based on the cavalry, and the people conquered were turned into allies who, wishing to regain wealth and land, had to attack other neighbours together with the Romans. Most of these Italian allies were under an obligation to provide cavalry. Further changes took place at the beginning of the 3rd century after the so-called Marius Furius Kamilus’ reforms. The tactical basis was then a legion divided into cohorts and manipulators, fighting not in phalanxes but in triple rows, which formed a checkerboard so that the next lines of fighters could move inside the formation.

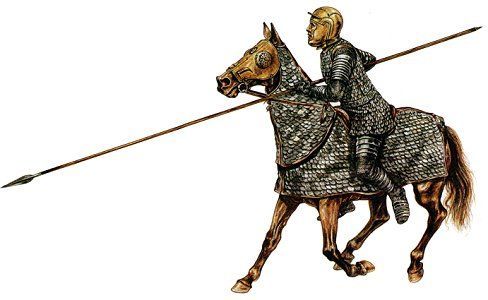

The entire legion now numbered 4,500 men with 320 horsemen. The armament of the cavalry during the times of the republic consisted of a long spear (hasta), leather armour, and a helmet (similar to those used in the infantry). The situation changed after the Second Punic War at the turn of the second and third centuries BCE. The Romans violently clash with the advantages of the heavy Numidian and Gallic cavalry during this period. Soon after the Punic Wars, the so-called rebellion of the Italian allies. Since then, allied and mercenary cavalry was introduced not only from Italy itself but from the entire Mediterranean basin, but they were equipped according to the Roman pattern. During the empire from I – II CE, the legion consisted of 300 – 500 horsemen, forming a unit called alae. The alae consisted of 16 turmae, 30 to 33 horsemen each. There were also larger units called cohors militaria with 700 – 750 horsemen in 24 turmae. A separate branch was the Imperial Cavalry (equites singulares imperatoris) created by Emperor Hadrian as a side branch. It consisted of 500 selected riders. During this period, in the Roman army, numbering from 400,000 to 600,000, cavalry played an auxiliary role, and the legionary infantry was still the decisive force for the fate of the battle.

The classic armament of the Roman cavalry from the heyday of the 1st – 2nd century CE are:

- HELMETS – they were definitely different in design from those used by the infantry. The ears were completely covered, at best there were small holes for hearing. Covering the ears was necessary because the enemy could easily make a hole in the soldier’s head in this place. Additionally, they did not have the same neck protection as foot soldiers. This was due to the fact that if the victim fell off his horse, he would most likely break his neck because of the rear peak. It also happened that soldiers wore real wigs, made of human or animal hair.

- SHIELDS – cavalry auxiliaries used shields similar in shape to those of foot soldiers, except that in the case of mounted horses, shields were generally flat. A shield like this was found in the 1st century CE. It had a hexagonal shape. It was about 125 cm long and 64 cm wide at its widest point. It protected almost the entire side of the cavalryman. The handle, unlike the infantry shield, was vertical. It was very heavy because it weighed about 9 kg, but it was also perfectly balanced. The oval type, found in Dura, dates back to the 3rd century CE, however, and there are also treasures much earlier. Like any other, the shield consisted of three glued layers of leather-covered slats.

- ARMORS – chain mails, scale armour or breastplates were used. One of the Belgian reliefs also shows a rather interesting type of armour, ie a combination of lorica segmentata with a chain shirt. However, we have no findings that confirm this relief.

- SPHATA – a sword sharper and longer at the end than the popular gladius, with a blade up to 91.5 cm long, and the width of the blade itself was approx. 4.4 cm. The handle was carved similar to the gladius ones. Probably carried on the right side.

- CONTUS – the longest spear used by horse riders – 3.65 m long-held in both hands, so the riders who used it did not have shields. It came into use in the 2nd century CE, however, it was equipped on a small scale. A typical spear was the shorter “lancias pugnatorias”, each horse also had “minores subarmales” or javelins. According to an inscription found in Britain dating back to the 1st century CE, each horse had one spear and two spears. Allies, had not two, but a minimum of three, javelins. Flavius reports that the allied cavalrymen usually had three javelins. Short javelins were inserted into the sheath on the right side of the horse, not on the back.

- RIDING ROW – horned saddle, fastened with a girth, with a breastplate across the horse’s neck and chest, with support connected with the under tail. The bridle had an additional vertical stripe, going over the horse’s forehead and connecting the noseband with the browband. All the stripes in the row were connected by rings through which the crossing stripes were interspersed. Decorative bumps were pressed into the rings. The bits, two-piece, broken most often of the Celtic pattern, with round stops, and curb bits with a chain under the horse’s lower jaw were also used. A thick sweatband was placed under the saddle, slightly protruding behind the saddle. The main weapon of the Roman horseman was a throwing weapon: javelins, jars, spears). The spatha long sword was considered an important but mainly auxiliary weapon.

One of the first records of the training is Ludus Troiae, described by the poet Virgil in an excerpt from the famous “Aeneid”:

They meet; they wheel; they throw their darts afar

With harmless rage and well-dissembled war.

Then in a round the mingled bodies run:

Flying they follow, and pursuing shun;

Broken, they break; and, rallying, they renew

In other forms the military shew.

At last, in order, undiscern’d they join,

And march together in a friendly line.

Roman history provides many interesting textbooks for horse fighting. Many of them have not survived to our times, but the ones that have survived show a very interesting picture (eg “Acies contra alanos” or “Ars Tactica” by historian Arrian). Until the end of the 2nd century CE, the army trained according to the principles generally known as hippika gymnasia. Let us mention here some basic training techniques of the Roman cavalry from this period. It is worth adding that the commands were usually held at the bearer’s sign, accompanied by an appropriate trumpet sound. It often happened that the horses performed a manoeuvre at a specific sound without waiting for the rider. It was the result of constant exercises conducted both in peace and war.

The exercises were usually carried out in the basic number of units called Turmae – it was a group of 30-33 legionaries divided into two teams. Both groups met in the ellipse-shaped training arena. The arena had a stand from which the viewers could follow the course of the exercises. When there was no arena, the exercises were carried out in grassy manages (prata). Both groups used the distinguishing Chełm family, which divided them into “Greeks” and “Amazons”. They were all wearing armour and full gear. The riders stopped so that the first horse had a slightly protruding head in relation to the next horse. This gave the effect of a pattern in the form of a line standing up the steps to the left. It was the so-called testudo chic. The unit positioned in this way was perfectly protected by large oval shields.

This arrangement required horses with short backs and necks. The exercise consisted in throwing unsharpened spears at the riders standing in such an array, so as to accustom them to calm and disciplined standing in one place in battle conditions. Roman horsemen used 3 pieces of lances tied by the right leg in a special case strapped to the saddle. After the initial warm-up, two old veterans were placed on very calm steeds halfway between the two groups. After a while the simulated attack was started by the first group, let’s call it “A”. At the command of the commander, the first rider started at a short gallop ahead and, in a circle, headed towards the two riders in the middle of the field. Moments after that, the attack was started by the second group – B.

Attacking a similar signal – the first rider set off to the right, wanting to cross the path of the legionary from group A. While riding at a gallop, soldier B threw his shield over the horse’s neck to avoid a blow from the veteran standing in the middle and at the same time threw his hole at rider A, then galloping as he was returning to his ranks. Meanwhile, legionary A, after repelling the attack and throwing it, turned left sharply and, passing two standing soldiers in a row, shocked them with his holes. After a successful attack, he turned right half-volt to greet the audience and return to his line.

The second exercise was performed in such a way that both teams were standing as before, except that they were located more to the left of the stand. Team A started the attack to gallop left perpendicular to row B. Group B had two options: 1. straight ahead and left 2. turning right in one spot. half-volts and up to cross the path of group A. In this clash, people passed “crosswise” in precisely measured time intervals, left and right. The soldiers attacked each other with their holes while crossing the cross. During the fight, one was covered with shields from the side and on the back. This type of attack and defence was called petrinos. After carrying out the petrinos, group A turned right in a large arc, and team B, after throwing two stationary targets, turned left. In front of the stand itself, team A voltage the returning group B. The legionaries from group A then made two throws: one straight ahead in the initial phase of the volte, the other in a party mode, leaving the volte to the straight, turned back and threw.

Another exercise was to arrange both groups in two parallel lines, each following the ensign holding the signum banner (most often the so-called Sarmatian dragon – a puppet with open feed stuffed on a long pole with a red bow). At the signal of the ensign and the blast of the trumpet, both groups turned towards each other by 45 degrees, simulating charges against each other and passing each side to the other, positioning themselves in the regular line behind the ensign.

Another basic exercise was the so-called Cantabrian gallop. It consisted of lining up both groups in close proximity to each other in a testudo pattern. Then the first rider of both groups moved diagonally forward making each one a large circle. Where the circles touched, they threw javelins at each other. After a while, each rider from both groups started to practice one after another, making a circle and throwing javelins at the point where the circles met.

During the exercises, the riders did not use iron points and the shields were lighter. Often spears had rounded tips. Javelins were thrown overhead. This method was reconstructed by researchers from the Austrian museum at Carnantum. During the javelin fighting exercises, leather browbones were put on horses, and the horse’s eyes were protected by openwork covers made of bronze. The riders also wore face-shaped masks, leaving only small openings for the mouth and eyes. Often during such exercises, the mythical fights of the Greeks and Amazons were recreated, so the masks often imitated the faces of women. This is confirmed by a find from the town of Straubing in Bavaria, where one of the women’s masks even had specially carved curls. They tried to teach the Roman cavalry to perform various exercises on the basis of reflex, without a moment of thinking. So these were exercises repeated ad nauseam. Simultaneous covering of the shield and throwing the javelin, throwing backwards, throwing as quickly as possible, as many javelins as possible, throwing the weapon during turns, and throwing the weapon back while tossing the shield at the same time. Of course, all exercises are carried out at the fastest pace. Roman horsemen also had to jump onto their horses from the ground in full gear on all sides.

The multinational cavalry of Rome abounded in riding masters but were also victims of their own inability. There are many descriptions where not only the rank and file legionaries but also the officers broke their necks by the horses bearing and not listening to them. Most, however, were eminent riders, performing truly acrobatic feats (Josephus from the description of the siege of Jerusalem):

And one, whose name was Pedanius, belonging to a party of horsemen, when the Jews were already beaten, and forced down into the valley together, spurred his horse on their flank, with great vehemence, and caught up a certain young man belonging to the enemy by his ankle, as he was running away. The man was however of a robust body; and in his armour. So low did Pedanius bend himself downward from his horse, even as he was galloping away: and so great was the strength of his right hand, and of the rest of his body: as also such skill had he in horsemanship. So this man seized upon that his prey, as upon a precious treasure; and carried him, as his captive, to Cæsar. Whereupon Titus admired the man that had seized the other for his great strength: and ordered the man that was caught to be punished for his attempt against the Roman wall; but betook himself to the siege of the temple, and to pressing on the raising of the banks.

– Josephus, The Jewish War, VI.2.8

Military exercises were also used:

- Quintena – javelin throw in full run to the stump.

- Palus – it was a stake with protruding beams so constructed that an advancing rider, not sitting in the correct posture, was hit on exposed places.

- Lusus troianus – two clashing troops of 19 horsemen (attack, retreat, truce). The game lasted no more than 10 minutes.

- Pyrycha militaris – training legionaries on similar principles as lusus troianus with the use of foot troops.

Volunteers from all over the empire joined the army. The service lasted 25 years. Initially, only wealthy people who owned land or real estate were accepted, but from the 1st century BCE, anyone could become a soldier. The citizens of Rome were legionaries and the rest served in the auxiliary forces. The smallest compact unit of the Roman army was contubernium – a group of eight soldiers who stood in one tent at a standstill. Ten contubernia made up a centuria (80 men), six centuries a cohort, and ten cohorts a legion. The first cohort had additional people for administration and support. The size of the legion during the heyday of the empire was 5,500 soldiers. The first units modelled on the Sarmatian and Parthian horsemen with an armoured horse are also dated to the reign of Emperor Hadrian.

The proportion of infantrymen to cavalry changed drastically after the defeat at Edessa, which the Romans suffered at the hands of the heavy Sassanid cavalry in 259 CE. There, heavy Persian cataphract formations were crushed to dust and dust 70,000 selected Roman infantrymen, and Emperor Valerian himself was taken captive to serve as a footstool for Sassanid king Shapur. The severe defeat of the Romans had a huge impact on the reform of the army made by Emperor Galien – son of Valerian. He distinguished the so-called vexiliationes – horse formations within the field army divided into equites promoti in northern Italy and Greece and equites scutarii in northern Africa and Croatia (equites dalmatae, equites mauri). During this period, units modelled on the hard-driving from the city of Palmyra emerged.

The city on the eastern fringes of the empire was famous for its super-heavy cavalry, protecting the entire horse with its armour. Since then, the Romans have armed separate units called clibanarii with lamellar armour for both the horse and rider. During the reign of Emperor Diocletian, two separate vexilliationes composed of horsemen with a strong Balkan influence (promoti, comites / lanciarii, iovani, herculiani) are created – they serve as an intermediate type between light west and heavy east driving. In the 4th century CE, the cavalry troops of Rome are already the most important military element. At the same time, after the defeat of the rebellious Goths in the battle of Adrianople in 380 CE, the Romans completely abandon the classic legion fight. Driving from this period, in the most basic division, is divided into:

- light driving – mauri, dalmatea, cetrati;

- heavy archery modelled on the influences of steppe peoples – equitus sagittarii, sogitarii clibanarii;

- breakthrough “shock” mine driving modelled on the Parthians, Sarmatians, Palmirians: catafractarii, clibanarii;

- driving hard on the Gallo-Roman models: promoti, scutarii, stablesiani, armigeri, brachiati, cornuti;

- irregular regional driving: equites indigenae;

- riding mercenary Germanic and Hun groups: pseudocomitatenes, foederati, bucellarii from the reign of Theodosius the Great to the generals of Stilicho and Aetius.

The situation with the Late Roman cavalry is a splinter in the heart of every historian of antiquity to this day. There were so many types of horse units and so much mixed up, with such extremely fluid and complex specializations that to this day no one is able to fully reconstruct at least half of the types of horse units for the Roman Empire in the 4th – 5th centuries. To this day, historians are not even sure what the terms cataphracts and clibanarii referred to in the Roman army. Some argue that these were two names defining the same type of heaviest type of cavalry, others separate these units by assuming that catafractii was driving heavy after clibanarii its elite. Clibanarii were a heavier variety of cataphracts, while the latter was intended to fight the infantry, they fought against the enemy cavalry.

The cataphracts fought in a formation consisting of several ranks, and the clibanaries formed the forehead and sides of the wedge formation, the centre of which were lightly armed horse archers cooperating with them. The offensive armament of the Clibanarius consisted of a long, two-handed spear called the kontos (used from the 1st century BCE to the 6th century CE), referred to in Byzantium as the kontarion (360 cm long), a sword and a reflective bow. The protective armament was a helmet, a small round shield (cataphracts rarely used it), and a chain mail caftan covering the body from wrists to knees over which lamellar armour, Saracen armour or a quilted fabric caftan (stitching / tigelaja) was applied. The leg cover was covered with chain braided trousers, additionally reinforced with metal rings.

The horse’s armour was a quilted dotter covering the horse’s rump, sides, chest, legs, mane and head, or sewn with plates of metal, horn or bone. Sometimes it was limited only to the breastplate and browband covering the horse’s nose, forehead and sometimes eyes. The monstrous confusion in the attempts to standardize the late Roman cavalry was effectively hindered by the pragmatism of the Romans themselves, where, for example, Italian horse spearmen used Celtic, Numidian, Germanic, Illyrian horse manoeuvres and even their battle cries, Armenian, Scythian and Hunnic archers, and heavy-armed and Parthian armed men. Probably to make the life of historians more pleasant, in practically all horse-drawn units, the banner was a symbol of a Sarmatian dragon with a red bow on a high spear, with which they were driven into battle to the beat of Gallic war trumpets and Parthian drums. The late Roman times were not enough for the period of mass employment of barbarian mercenaries with entire units, who hastily armed themselves with Roman weapons and Roman horses.

This situation is perfectly illustrated by the document Notitia Dignitatum, listing the types of various Roman troops from the end of the 4th century. The Romans, of course, never used stirrups, but there are some traces of attempts to use them, in the form of straps for the left leg. In the Budapest Museum, a leather loop for the left leg is shown on the tombstone of a horse legionary from the 1st century CE. It was probably used for boarding or for constipation when fighting with a javelin. However, this is an exception to the rule and should be treated more as a curiosity than evidence of the use of a prototype of a stirrup. The late Roman ride is interestingly described by the historian Vegetius:

They had wooden horses for that purpose placed in winter under cover and in summer in the field. The young soldiers were taught to vault on them at first without arms, afterwards completely armed. And such was their attention to this exercise that they were accustomed to mount and dismount on either side indifferently, with their drawn swords or lances in their hands. By assiduous practice in the leisure of peace, their cavalry was brought to such perfection of discipline that they mounted their horses in an instant even amidst the confusion of sudden and unexpected alarms.

As you can see, the late Roman ride was no joke. Often a wooden log suspended at an appropriate height was used for jumping on the horse training. The Roman cavalry made a 20-mile training march three times a month, where one Roman mile equals 1,479 meters. After all, great Rome is no joke…