Starting from the founding of Rome, the father of the family had extensive, almost unlimited power in relation to his family – literally the life of the offspring was in his hands. He had the right not to accept a child, regardless of his sex, even if he was healthy. The law of the Twelfth Tablets adopted in the early stages of the republic (450 BCE) even demanded the elimination of sick or weak children: “A dreadfully deformed child shall be quickly killed” (Table IV).

In the first century BCE for the first time, legal provisions appeared to increase the birth rate – laws were issued against murderers and poisoners: in 81 BCE lex Cornelia de sicariis et veneficiis, and in 55 BCE lex Pompeia de parricidiis. They were clearly procreative, hence the mother who had committed him was also punished for the murder of the child. However, the law at that time was not intended to protect children, and taking away the mother’s right to decide about the child’s life was dictated by the privileged position of her father. A woman could not decide to deprive her husband of an heir.

During the principate, extramarital children – especially girls – were abandoned, and over time, at the turn of the third and fourth centuries, this practice was extremely widespread, which was met with widespread disapproval of Roman philosophers – Musonius (1st century) and Epictetus (2nd century). However, the father who originally abandoned the child had the right to think, considering the patria potestas, to demand the surrender of his descendant from the one who found him, without regulating the financial issues related to his maintenance.

The empire at the beginning of the third century. During this period, a rescript was promulgated against abortion as well as against abandoning children.

Infanticide was legally sanctioned as punishable only in the 4th century. Perhaps the change in sentiment could have been influenced by the spread of Christianity. Both killing and abandonment of a child who was considered a crime was prohibited. The killing of the child was not only against human rights, but above all divine, which justified the heavy punishment applied to the perpetrator of such an act. At the synagogue in Elvira, which took place around 295–314, it was assumed that a married woman who would give birth to a child born out of wedlock and kill her should repent and cannot receive the sacrament of the Eucharist; this sacrament could only be given to her on her deathbed.

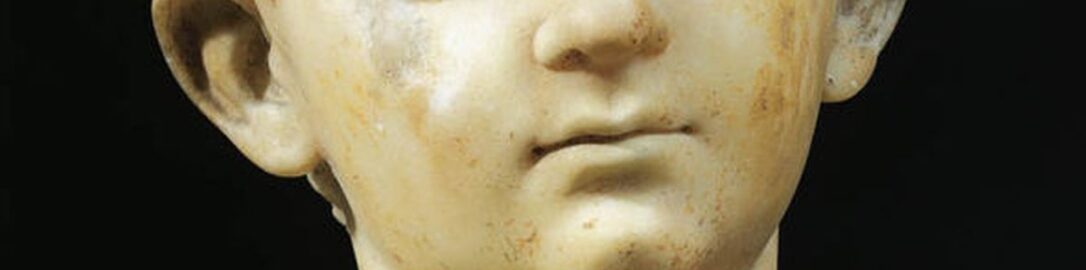

A breakthrough in criminalizing infanticide was the legislation of Emperor Constantine (306–337), which provided that the mother who killed her child could be tortured and then drowned in a bag of snakes (poena cullei). The legislator referred in this way to a very old punishment, so far imposed for the murder of close relatives. The Emperor Valentinian I (364–375) considered killing a newborn child as murder (374).