The Roman fullones were supposed to both clean and smooth the material after receiving it from the weaving workshop, as well as clean the clothes from dirt and bleach or enhance the colour. Fuller workshops were called fullonicae.

The main source of information about the work of fullers in ancient Rome is Pliny the Elder and preserved frescoes, including in Pompeii. The work of fullers consisted of three stages.

In the first phase, the fullers threw clothes into the basins, filled them with water, with cleaning agents (including urine1), and then stood with bare feet for the prepared “workshop”. Employees pressed their feet and scrubbed and squeezed clothes/material with the help of their hands. The purpose of this process was to remove all grease and other dirt from the material.

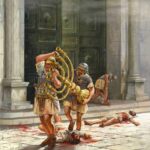

After the washing was done and the material soaked well, the remaining dirt had to be rinsed. This was done with the help of clean water in a complex of large tubs that were connected to each other. The bathtub was connected to the sewage system; water flowed successively through subsequent baths, which several employees could use simultaneously. The material was immersed in the tub and moved in flowing water, against the current.

Finally, the washed material was hung before the plant dried. Then the dry wool was brushed and dug out using special tools and even hedgehog skin.

The material was also subjected to whitening treatments. For this purpose, the so-called viminea cavea – a special basket on which the material was spread. Then sulfur was left on the ground under the material, which has a bleaching effect. Pliny the Elder also mentions that a soil called terra simolia was used, which when rubbed into the material clearly whitewashed it. The fullones also dealt with the straightening of materials using special presses.

Who were the fullers? Most of the work was done by the poor (in municipal works) or slaves (in private rural estates). So far, the remains of such places have been found, including in Ostia, Pompeii, Florence or Delos.

As it turns out, the work of fullers was very important from the point of view of the Roman state. Foluszniks were responsible for the clothes that were washed. In the event of failure to return the goods or damage to the colour/material, they were subject to penalty. A law has even been passed regulating what “means” can be used in manufactories to remove dirt so as not to damage the material. Interestingly, there was a belief that the clothes that had passed through the fulling factory were losing their value. Despite such an opinion, many Romans used their services, due to the fact that bright clothes that got dirty easily were in common use.

The fullones, like many other professions in Rome, were associated with the collegium, which represented their interests and supported the professional group.

Finally, it is worth adding that over time urine has become a real commodity and many people collected it and then delivered it to full-scale factories for a fee. In connection with this practice and the desire to provide additional funds to the state treasury in 74 CE. Emperor Vespasian introduced the urinary tax (urinae vectigal). His son Titus criticized the new law. Then Vespasian:

[…] held a piece of money from the first payment to his son’s nose, asking whether its odour was offensive to him. When Titus said “No,” he replied, “Yet it comes from urine.”

– Suetonius, Vespasian, 23

After Vespasian’s death, Titus withdrew the tax.